Public Economics - DARP

advertisement

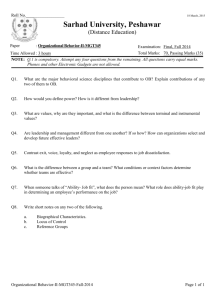

Summer 2006 examination EC426 Public Economics 2004/2005 and 2005/6 syllabuses only – not for resit candidates from earlier years Instructions to candidates Time allowed: 3 hours This paper contains twenty-one questions and is divided into three sections of which two are relevant for any particular candidate. Answer two short questions and one long question from section A. Answer two short questions and one long question from EITHER section B OR section C. Each short question has a weight of 10% (of the overall mark) and each long question a weight of 30%. In multipart questions, answer all parts. Calculators are not allowed in this examination. © LSE 2006/EC426 Page 1 of 5 SECTION A (Required for all candidates) Short questions: Answer TWO questions (weight 10% each) 1. Explain why externalities are a potential cause of “market failure”. Will they inevitably require state intervention to ensure efficient outcomes? 2. What is “moral hazard”? How will this phenomenon affect the design of social insurance schemes? 3. What is the Corlett-Hague rule? What is the relationship between the CorlettHague rule and the original Ramsey rule? 4. Define the Loeb-Magat mechanism and discuss its significance in the presence of (i) hidden knowledge, and (ii) hidden action. Long questions: Answer ONE question (weight 30%) 5. 6. 7. Critically examine the following statements about the welfare-economic basis for redistribution: (a) “If social values give priority to the poorest individuals then this will ensure equality of outcome” (10 marks) (b) “If social values are determined by individual preferences behind a veil of ignorance then this will ensure that priority is given to equality of outcome.” (10 marks) (c) "Social values should reflect individual preferences. So the government should have no role in redistributing income because all distributional objectives can be achieved by private charity." (10 marks) (a) Explain the role of the incentive-compatibility constraint in the income tax design problem. (10 marks) (b) Will such problems arise in the case of a linear income tax? (8 marks) (c) Will the general optimal income tax model provide an argument for taxing the rich at a higher marginal rate than the poor? (12 marks) (a) Is it possible to devise an allocation mechanism for public goods such that truthful revelation is a dominant strategy? (15 marks) (b) Can lottery finance lead to the efficient provision of public goods? (15 marks) © LSE 2006/EC426 Page 2 of 5 SECTION B (Selected topics in public economics) Short questions: Answer TWO questions (weight 10% each) 8. Define and explain “sequential dominance.” What role does this principle have play in assessing the distributional impact of taxation and spending policies? 9. In an economy with local public goods, will the Tiebout mechanism result in an efficient allocation? 10. Will a federal social insurance scheme oversupply regional risk-sharing? 11. Do ‘green’ taxes generate a ‘double dividend’? Long questions: Answer ONE question (weight 30%) 12. 13. 14. (a) What evidence is there that wealth taxation can affect trends in economic inequality? (10 marks) (b) How will changes in family structure be expected to alter this effect of wealth taxation? (10 marks) (c) The Daily Express has been running a campaign to abolish inheritance tax. Explain the likely long-run consequences of such a policy change. (10 marks) (a) “[The] simple version of the Allingham-Sandmo model has been criticized on the grounds that it fails a simple reality check.... The intriguing question becomes why people pay taxes rather than why people evade” (Slemrod and Yitzhaki, 2002). Explain. (12 marks) (b) To what extent have alternative models of compliance addressed the problem noted in part (a)? (18 marks) (a) “‘Capital ownership neutrality’ should be a key objective of any future reforms to corporate taxation.” Discuss. (12 marks) (b) How and why might the existence of trade costs alter the outcome of tax competition for foreign direct investment? Does the presence of a consumption tax affect your answer? (18 marks) © LSE 2006/EC426 Page 3 of 5 SECTION C (Macroeconomic policy analysis) Short questions: Answer TWO questions (weight 10% each) 15. What is “debt overhang” and the debt Laffer curve? Why is voluntary debt forgiveness rarely observed in practice? 16. A hair cut is more than ten times more costly in London than in Lima (Peru), holding quality constant. Propose a model to explain this price difference. Carefully state your assumptions. 17. Provide one argument in support of and one argument against having a lender of last resort in international markets. 18. Some have argued that lowering tariff and non-tariff barriers in international trade can lead to higher capital flows from rich to poor countries. Explain the channel through which this might happen. Long questions: Answer ONE question (weight 30%) 19. Consider a small open neo-classical economy with two composite goods, tradables and non-tradables; total factor productivities in each sector are given by AT and AN. Labour is mobile across sectors but there is no international mobility. Capital is perfectly mobile both across sectors and internationally. Denote by p the price of the non-tradable composite relative to the price of the tradable; the price of the tradable composite good is normalized to one; call ki (i =T,N) the capital labour ratio in the tradable (T) and non-tradable (N) sectors, respectively; r is the international real interest rate in terms of tradables, and w is the wage rate in terms of tradables. The equilibrium conditions in the tradable sector are: (i) (ii) AT f’(kT)= r AT [f(kT)- kT f’(kT )]= w (a) Briefly explain these equations and write down the corresponding equilibrium conditions for the non-tradable sector. (8 marks) (b) Consider an increase in productivity in the non-tradable sector. What is the effect of this increase on real wages (w), relative price (p), output, and capital-labour ratios in the two sectors? (12 marks) (c) What are the effects of a decrease in r on real wages (w) and the relative price of nontradables (p)? (10 marks) © LSE 2006/EC426 Page 4 of 5 20. 21. Consider a small open endowment economy. The representative agent in this economy lives for two periods, 1 and 2, and consumes a single tradable good. The agent maximises U = u (C1 ) + βu (C 2 ) where C1 and C 2 are the consumption levels in periods 1 and 2 respectively, and β is the subjective discount factor. Endowments in periods 1 and 2 are Y1 and Y2 , respectively, and utility flows are u (Ci ) = ln(Ci ) , where i denotes periods 1 or 2. The real interest rate for borrowing or lending in the world capital market is r . (a) The country can borrow and lend at the world interest rate r . Write down the intertemporal budget constraint and the maximisation problem of the representative consumer. Derive the Euler equation. (9 marks) (b) Let Bt +1 be the value of the economy’s net foreign assets at the end of period t. Assume that the economy starts off with zero foreign assets ( B1 = 0 ). Define the current account. What is the current account in period 1 (call it CA1 )? What is the current account in period 2 (call it CA2 )? Show that CA1 = −CA2 . (10 marks) (c) Assume that Y1 = Y and Y2 = 2Y . Derive the consumption levels C1 and C 2 as a function of r , β and Y . What is the balance of the CA1 ? Provide an intuitive explanation for this result. (11 marks) Consider the case of a debtor (for example, a domestic corporation) in extreme financial distress, unable to meet its debt obligations as they fall due, and that likely needs a partial cancellation of debts. Suppose there are many creditors with conflicting claims. (a) At each stage of the financial restructuring, collective action problems might affect the readjustment of debt claims to the detriment of the creditors as well as the debtor. Provide three examples of collective action problems. (10 marks) (b) What provisions can address these collective action problems? (Think of Chapter 11 in the US Bankruptcy Code). (10 marks) (c) Many authors have proposed setting up an international bankruptcy court, with powers similar to a domestic bankruptcy court as in Chapters 9 and 11 of the U.S. bankruptcy law. Discuss why an international bankruptcy court is more difficult to set up than a domestic bankruptcy law. (10 marks) © LSE 2006/EC426 Page 5 of 5