Promoting a 'duty of care' towards animals among children

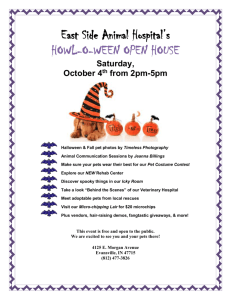

advertisement