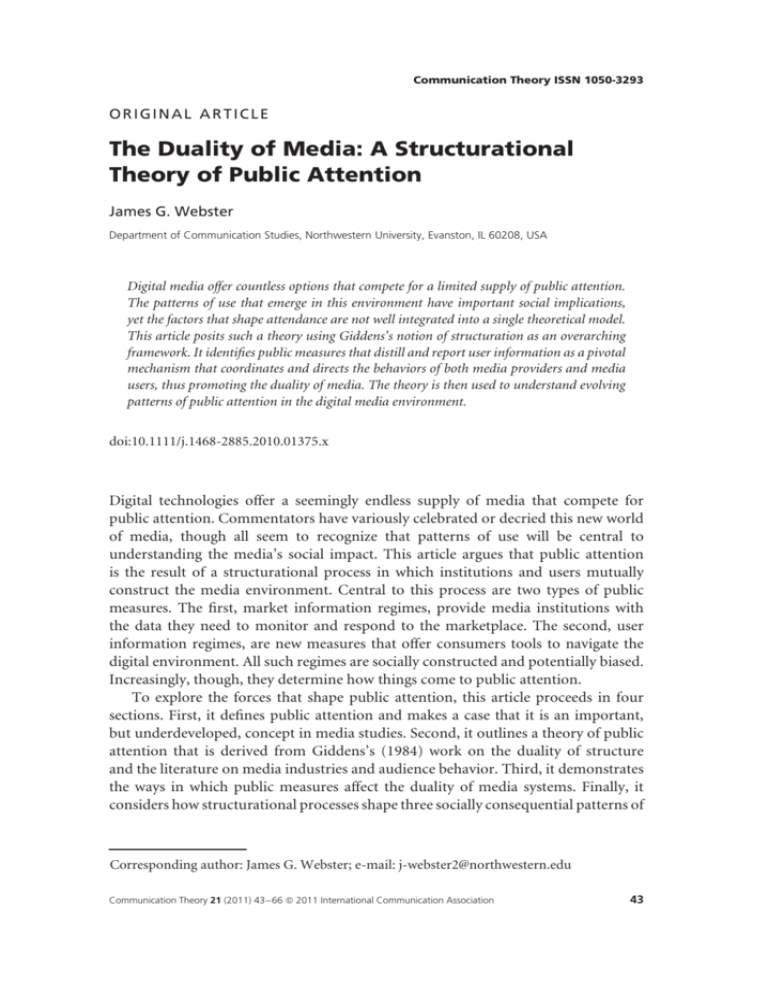

The Duality of Media: A Structurational Theory of

advertisement