Kālacakra and the Nālandā Tradition: Science, Religion, and

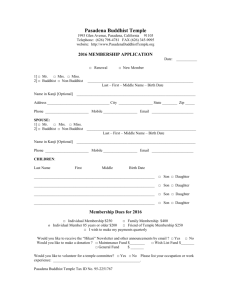

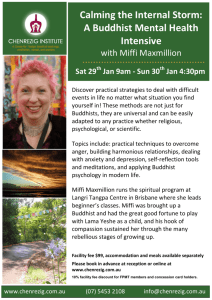

advertisement