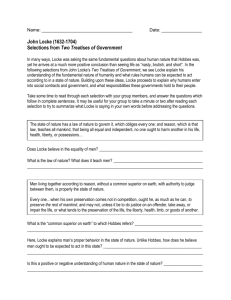

Saving Locke from Marx - George Mason University School of Law

advertisement