SSRC Working Paper No. 2014-2 - Social Security Research Centre

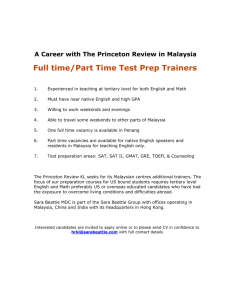

advertisement