'Pioneering' and 'settling' activities of youth workers

advertisement

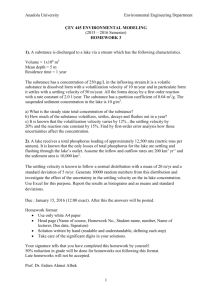

of specific categories of young people. They also, and more fundamentally, are concepts which signal a particular kind of society, a particular type of social system, particular sorts of social relationships. Gaining an understanding of and empathy with these young people is only part of what youth workers require. The perceptions and character of youth work intervention will be crucially determined by how the empirical realities of poverty, homelessness, and abuse are interpreted; by whether or not these interpretations are linked to the deep structures of sexism, racism, and class struggle which constitute the basis of oppression, exploitation and disadvantage; and by how recognition of the causes of youth problems can be translated into appropriate strategies at the level of day-to-day youth work practice. In a nutshell, our research inevitably leads to questions concerning the ideological and political basis of contemporary youth work, and once again illustrates the need for on-going debate and discussion over the aims and objectives of different kinds of youth work practice. Third, any discussion of youth needs (as indicated by user population and type of service provision) and youth work practice (as shaped by welfare concerns and the consciousness of youth workers regarding the nature of their interventions) must also take into account the impact of state funding and policy on youth service provision. Our research appears to show that, within the context of existing government guidelines regarding priority targeting (such as young women, non-English speaking migrants and Aborigines), these particular categories of young people are being excluded or have lower participation depending on the service provided. Again, qualitative research is needed in order to determine whether this is due to factors such as the type of youth work undertaken (which is also influenced by the quality and quantity of training available) and/or whether it is due to the general constraints of restricted funding, inadequate administrative support, and poor 50 working conditions and wages in the non-government youth field, all of which can affect the capacity of youth workers to broaden out and adequately work with particular groups of young people. More generally, questions can be asked as to how state economic and welfare policies, as well as those regarding youth service provision, are influencing the orientation and content of Australian youth work (White 1989, 1990ab). Further to this, consideration must be given to the economic role of youth workers in a period witnessing major financial stresses on the welfare system as a whole, such as cost savings to the state in the form of low paid and volunteer welfare workers and greater selectivity in welfare payments. Consideration must also be given to the social role of youth workers given "their target group and state concerns to render youth issues less visible to the public eye, such as by keeping these young people preoccupied and off the streets, or by offering minimal welfare and accommodation support. This two-part series has attempted to identify certain characteristics of youth workers, the nature of the services they provide, and the young people who use those services. Arising from the descriptions provided in this and our earlier paper are a number of issues which deserve further research and further analysis. Each of these issues directly or indirectly revolves around whom youth workers actually work with, the substantive content oftheir practice, and the self-identity and selfconsciousness· of youth workers as they participate in broad welfare and community development types of activities. It is our hope that the findings and concerns we have raised will be useful in further developing creative and critical discussion on the nature of Australian youth work today. References Ewen, J. 19S3, Youth in Australia: A New Role and a New Deal for the 80s, Phillip Institute of Technology Press, Melbourne. Jeffs, T. & M. Smith (eds) 19S5, Introduction to Welfare and Youth Work Practice, Macmillan Education, London. Maunders, D. 19S4, Keeping Them Off The Streets: A History of Voluntary Youth Organisations in Australia 1850-1980, Phillip Institute of Technology Press, Melbourne. Nava, M. 1 9S4, Youth service provision, social order and the question of girls, in A. McRobbie & M. Nava (eds), Gender and Generation, Macmillan Education, London. Omelczuk, S. 19S7, Training: How It Affects Youth Workers and Young People in the Northern Territory, Steering Committee on Youth Sector Training, Darwin, N.T. Omelczuk, S., Underwood, R. & White, R. 1991, The characteristics of youth service users, Youth Studies, vol.lO,no.l,pp.62-6. Quixley, S. & Westhorp, G. 19S5, Youth Workers' Access to the Field in South Australia, Youth Affairs Council, Adelaide. van Moorst, H. 19S4, Working with youth: A political process, in Nationwide Workers with Youth Forum, Beyond the Backyard, Melbourne. Westhorp, G. 19S5, The History and Development of You th work in Australia, YACSA, Adelaide. White, R. 19S6, Youth Worker Training in South Australia: Issues and Responses, Youth Worker Training Development Committee of South Australia, Adelaide. White, R. 19S9, Does youth policy mean no m ore youth workers? Youth Studies, vol.S, no.3, pp.26-9. White, R. 1990a, No Space Of Their Own: Young People and Social Control in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne. White, R. 1990b, Social justice, skill formation and Australian youth work practice, Youth and Policy, no.30, pp.1-7. White, R., Omelczuk, S. & Underwood, R. 1990, Youth Work Today: A Profile, Technical Report No.25, Centre for the Development of Human Resources, The authors are from Editll Cowan University, Perth. Rob IVhite is lecturer in Youth Work Studies, Research Assistant Suzanna Omelczuk and Associate Professor Rod Underwood are at the School of Community and Language Studies. Youth Studies May 1991 'Pioneering' and 'settling' activities of youth workers NEVILLE KNIGHT argues here that the activities of youth workers may be usefully categorised as pioneering and settling, with the latter category being further divided into traditional and bureaucratic. He develops a typology based on Weber's ideas around these concepts, and using this typology, the goals and activities of three youth workers from Britain and Australia are examined on a case study basis. N THE development of any area of human activity we may define Pioneering as breaking new ground, thereby bringing about changes in people and situations. Particular individuals who undertake pioneering are those who are at the frontier of inquiry or enterprise. Here our usage of pioneering also refers to the activities of individuals who are not guided or constrained by traditions and who are not afraid to break away from bureaucratic practices within an organisational framework. Pioneering implies that total separation from that framework may occur if it is believed desired purposes cannot be achieved within it. In so far as pioneering involves other people, the legitimate authority of those who undertake it is based on personal trust and a belief that such individuals know where they are going and how to get there. Their authority bears a close affinity with Weber's charismatic type, although according to our definition it is not necessary for I Youth Studies May 1991 those who undertake pioneering to have had a "revelation" (Weber 1964, p.328). Even though these individuals may not have had a revelation they are being regarded in this paper as visionaries. But in this case they are visionaries who actually initiate new developments or approaches, not just dream about them! In its pure form pioneering is undertaken by charismatic leaders who abhor routine structures and depend entirely on their personal qualities to involve others in what they are doing. But such relationships are transitory, and the charismatic authority on which they depend must, according to Weber (1964, p.364), become "traditionalised or rationalised or a combination ofboth" , if those relationships are to become more stable and permanent. The other type of activity can be termed "settling". In this paper settling is of two kinds: traditional and bureaucratic. Traditional settling conforms to traditional rules and practices which form an established framework within which goals are shaped and activities are carried out. In so far as settling accords with these rules and practices, the authority of leaders undertaking this kind of activity may be regarded as traditional (Weber 1964, p.341). Bureaucratic settling expresses the requirements of an "office" and shows acceptance of recognised authority within a hierarchical framework. Leaders undertaking settling activities of a bureaucratic kind occupy formal positions in a hierarchy of offices which define the institutional status of oGcupants. The conduct of those who occupy a particular office is regulated by rules and other forms of supervision and control exercised by those in a higher office. The authority of such leaders is of a rational-legal kind which is derived from the office itself and not from any personal qualities of the individuals occupying such offices (Weber 1964, p.330). 51 The distinction being made between pioneering and settling draws on Weberian ideas. Accordingly the distinction is not new but it has yet to be applied in this way to the activities of youth workers, as far as the writer is aware. The distinction is important because the shape of youth work will be affected by how much pioneering and settling activities occur. Too much pioneering may result in lots of new projects starting but never becoming properly established. Too much settling may result in unchallenged acceptance of existing forms of youth work which could be preserving practices relevant only to a previous generation of youth, and an inefficient usage of resources. The distinction is also important because it assists in the process of matching youth workers with appropriate jobs. Some youth workers may need to be employed for pioneering work among particular groups of young people not effectively reached by traditional youth services, for example, drug addicts or long-term unemployed youth. Other youth workers may need to be employed for settling work to maintain existing programs which already cater for significant numbers of youth, such as in youth centres or schools. It can be postulated that mismatching the type of youth worker with the kind of job to be done will result in frustration and disillusionment on the part ofthe youth worker, a waste of an agency's resources, and even the disintegration of the youth work itself. In youth work we can expect there to be both pioneering and settling activities. In practice, some youth workers may incline towards one type of activity more than the other. Others may undertake pioneering activities at one stage oftheir career as youth workers and settling at another. In addition, there may be particular youth workers who combine pioneering and settling, moving from one to the other depending on the circumstances. The activities of such youth workers may be best described as pioneering-settling. The above discussion leads us to consider how pioneering and settling type activities of youth workers may be recognised. In this paper activities which are new or break with existing practices and conventions are described as pioneering. If a new way is used to organise a program, or if a structural change is made to decision making groups and processes within a youth club, then these would be regarded as pioneering activities. Another example of pioneering would be if a youth worker were to use an innovative approach to reach out to a group of young people not previously contacted by conventional methods. Activities of youth workers which produce stable patterns of human interaction based on routine procedures and programs are described as settling. If these activities conform to conventional rules and practices and are accepted as having always been done that way, they would be called "traditional settling". Activities which indicate a youth worker has accepted direction from those with recognised authority within a hierarchical framework, or activities which are performed as expressions of a youth worker's office, would be called "bureaucratic settling". In the remainder of this paper the goals, activities and achievements of three youth workers from Britain and Australia will be examined on a case study basis. Specifically, how these youth workers seek to achieve their goals will be considered. What is reported here is part of a larger study involving interviews with youth workers mainly from Britain and Australia. Youth Worker Profiles _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ MAUREEN Maureen (aged 29) grew up in Birmingham and trained as a teacher. She married a teacher, but has no children. She expressed a particular concern for young unemployed women who did not use existing youth services. Maureen gave up her job in a youth club to become a detached worker with unemployed youth and was employed in that position by the Inner London Education Authority. Maureen sought to improve the position of young unemployed women. She felt there was "a huge difference between unemployed young 52 men and unemployed young women, and that is because of the inequality". She set as a personal target to help "those young women get a foothold to fight back". Maureen envisaged that the young wom\}n she worked with would become "autonomous people" and "grow in confidence" as they began to look after themselves and develop to the point where they could say: "Yes, I have got skills and I am an important person." The thrust of her activities was to assist young unemployed women to cope with a society she saw as hostile to them. She sought through her involvement with these women to promote values opposed to those generally accepted in society which emphasised capitalism and materialism. I think the work that some of us are doing is even more exciting because we are indoctrinating them into the opposite. I think we are looking at alternative values because it is Tory thinking, capitalist thinking, and it is about how much you have got, and not who you are or what you have got to offer, and that puts pressure on young people. So I would say I am trying to slow that process down. The depth of Maureen's commitment to her task is shown in this comment: It's hard and it's tough and it's a fight. It's not easy and sometimes I ask whyIdoitbecauseitcould be much easier going into a classroom and giving part of myself. I think in youth work you give everything, if you believe in what you're doing. Youth Studies May 1991 In her position as a detached youth worker Maureen translated into action her vision of helping young unemployed women to lift their heads and feel important. Maureen's immediate goal was to make contact with such women because she had no ready made group to work with. She explains how she did this: "There was a lot of home visiting in which I worked closely with Social Services and Career Services, to get hold of the names of young women on housing estates, and contact them, and then develop that into a piece of group work." From her contact with 50 or 60 such women Maureen developed a group of 12 women who were interested in meeting with her on a regular basis. She referred to this process as "creating pieces of work with unemployed young people". In this work she recognised the importance of winning the trust of the young women before being able to do anything more with them: "I had to build up a confident relationship so that they would trust me, and then I organised trips they wanted to do." In reflecting on her work Maureen elaborated on the central importance of relationship building and the impact of this on her own thinking: One of the findings was that with working with young people in a detached method the relationship becomes the all important thing. There aren't any rules or regulations made, no bumph is in the way, which is the extreme opposite for me from teaching. I feel that I have come down a path with that in relationships with young people. It is totally on their terms, it has to be. Maureen enjoyed success in her work. She referred to the group she had just left in her previous job as coming on in "leaps and bounds". For her the most important thing was that "they recognise this themselves". But while Maureen could draw satisfaction from the changes in the lives of these women she nevertheless faced many difficulties which seemed to almost overwhelm her. When asked whether she ever stopped and wondered whether it was all worthwhile she said: "Yes, every day. It is very rarely the young people. It is the frustration of management, and working in such a sexist and racist institution. " This frustration which Maureen experienced may be linked with her declared long-term goal of getting into management so that she could "change policy from the top" with a view to further assisting unemployed young people. She had undertaken pioneering activities with young unemployed women untouched by the existing youth services and had the satisfaction of seeing some overcome personal problems. But Maureen was not content with this success. She wanted to see changes occur in management and was looking for ways she could break new ground on behalf ofthe young unemployed women for whom she felt so deeply. STEVE Steve (aged 39) grew up in a middle class family, then worked at the Post Office Telephone Service in London before training as a youth worker. He is married with three children and is employed as Warden of a Youth and Community Centre. The Centre has a variety of community groups using its facilities during the day which involves Steve in relating to the adults responsible for these groups and in being a caretaker of the Centre. He is also leader of a youth club for 12 to 18-yearolds. Steve has difficulty in satisfying the seven-man executive responsible for activities and approving usage of the Centre, and the management committee responsible for the upkeep of the buildings and for finance. He has, however, learned to live with both bodies. Youth Studies May 1991 Steve is directly accountable to the District Youth Officer with whom he meets monthly. When asked what the District Youth Officer expected of him , Steve's reply suggests that he doesn't find meeting with him particularly helpful. I don't know. Well, running the youth club is the thing they expect, an d the development of the youth club. Atthe moment it is probably staff relations we are working on - making sure that staff meetings are held regularly. They are also concerned about the administration of the place. So they are concerned about sending out agendas and meeting on time, and all this rubbish. Steve describes a successful youth club as one: .. .run by a good team of youth workers, where young people are offered opportunities to take part, where they feel there is a place for them to come to, which accepts them for what they are. When asked whether he had a plan for achieving his goals, Steve'sreply indicates the difficultyhehadingetting his staffto agree on what they were doing. One of the problems we are working at is getting a team ofstaff devising what their aims are as a team. I wanted to get something down in writing. We have started to adopt one ofthe objectives that the South East area full-time team have adopted. Steve thought the professional youth worker should be thinking about the development of young people and the development of staff working with young people. He thought there should be more attention given to working with the juniors and specifically with girls. He also believed that a health education program should be introduced. But none of these ideas had reached the planning stage and Steve gave no indication of actively seeking additional resources to make them happen. Comments like, "They don't pay part-time staff for working with the juniors like the London authorities do", suggest that he was accepting that no new developments would occur in such areas. When asked what goals he thought he had already achieved, Steve indicated partial satisfaction with the outcomes of his work. We have got a youth club going which involves young people in the area. 53 It is a place where young people like to come along to. We have provided some of the opportunities that I laid out in my original aim - not as many as we would like. Sometimes the resources and buildings don'treally lend themselves to ad infinitum things going on at once. Steve seemed to long for a more settled life in which there were fewer disruptions. He found the most difficult thing about being a youth worker was that everything was "always changing", and "you have to keep dealing with new situations". But he was philosophical about such matters when he said: "But the factis sometimes you can't let up on thinking about how you are going to deal with another situation. You can't sit back." In respect to bureaucratic procedures Steve was ambivalent. He thought the concerns of the District Youth Officer about the administration ofthe Centre, the sending out of agendas and the holding of meetings on time were "all rubbish". But he also thought it was a problem that his own staff team could not get their aims down "in writing". Steve was not the kind of person to rock the boat. He was comfortable in his job which involved him in a mixture of activities. These Included relating to the leaders of various community groups which used the Centre, keeping accounts and running a youth club. This club had its own recurring activities such as badminton, discussion groups, interclub visits and trips. Steve accepted without question this regular pattern of activities as defining the main part of his job. This suggests that many of his activities may be best described as traditional settling. Although Steve may have wanted to sit back and avoid change, he recognised that he couldn't always adopt this position, especially if he was being pressed by those in authority over him. When faced with such a situation he attempted to meet the demands of those in power such as the District Youth Officer and the Management Committee, even when he wasn't in full agreement with them. Despite his problems in coping with staff conflict, Steve had learned to manage his work environment reasonably well and had established his routines in his nine-year term of office by undertaking activities which were mainly of a traditional settling kind. He did not seem to have a particular message to conveyor mission to accomplish among the young people with whom he worked. of his work was "to proclaim the Good News that God loves people and wants to enrich their lives". Although he took some comfort in knowing that he had the support of the church leaders in what he was doing, he did not take this for granted and maintained close contact with them. But while he clearly welcomed this contact, Dave reacted against the idea of being told what to do: "They don't really tell me much. I tell them what I'm doing." Dave's independence and confidence is also shown in this comment: "The vicar and wardens get together and knock around a lot of stuff, but really the youth ministry is put in my hands and if I keep doing it effectively and people keep coming, then I do whatever I like, and they trust me." As part of his strategy for training leaders, Dave formed cell groups where the leaders had "some small responsibility for a little group of people". Each cell group consisted of six or seven members including a leader and an assistant. The responsibility of the leaders was gradually increased as they began to look after members more fully physically, spiritually and emotionally. Dave not only invested much of his time with individual members but he also worked at improving the integration of the various youth groups within the church. importance of having a common aim shared among them. In this process he saw himself as a manager and trainer of the key leaders of the groups. In addition to training leaders, Dave developed new activities where he believed there was a need for them. DAVE Dave (aged 37) grew up in Sydney and trained as an engineer. He has no formal training as a youth worker. His interest in youth work dates back to his involvement in a church youth group; then, after some years of working as an engineer, he was invited to be a youth worker at a Melbourne church. He held that position for six years and is now in his second position at a different church. His wife and two children support him in his youth work and he uses his home for many youth club activities. Dave's religious experience affected his goals as a youth worker. He said that he was committed to sharing God's love with the kids. He was also convinced that "relationships with people are the essence of the quality of life" and that it is "through a loving relationship with God that relationships with people can form in harmony". He believed the church leaders shared his view that the aim 54 I normally put aside two or three hours a week for overall planning integrating. I'm responsible for the integration of junior high school ministry, senior high school ministry and the Alpha group which is secondary into mid twenties. Elsewhere Dave talked about the young adults being the key people in the interface between the groups and the I've gradually taken up the things I had the ability to do that were not being done - hence something like family camping, evening music. I don't really see myself as a musician but it seemed to be an opportunity and I recognised some abilities and so I worked it to help that to happen. Dave believes he has achieved his goal of training leaders on-the-job. He has discovered their abilities and provided opportunities where they can be tried out. He has the satisfaction of knowing that he is "loved and appreciated by a lot of the Youth Studies May 1991 kids" he has shared his life with. Occasionally, he has been criticised "for being too outrageous or treading on traditions a bit too much", but he said he knows that most "support the goals to which I am working to the best of my ability". He added: "I'm able to accommodate criticism and to screen out what is helpful and just let the other stuff pass on." At times Dave showed he could undertake pioneering work by the way he formed a team of leaders and constructed opportunities for them to develop their leadership. He also pioneered new activities such as family camping and music groups. But he undertook not only pioneering activities, Conclusions Pioneering involves working at frontiers to bring about changes in people and situations. In youth work it may take the form of developing new groups or activities which do not conform to existing practices - as seen in Dave's club with the starting up of music groups and a family camping program. Pioneering may also take the form of an innovative approach to youth work which breaks with conventional practices, or to working with a particular group of young people in a different way, as was the case with Maureen's work with young unemployed women. Maureen originally "started in a voluntary youth club" but left after 18 months to become a detached worker "to coordinate unemployed work". In this position she didn't work with young people at first so the job was reviewed and she "started to create pieces of work with unemployed young people in a detached method". Her approach differed from her previous experience with youth in that it depended entirely on relationship building with these women "on their terms" in a context largely of their choosing, which was outside of traditional and bureaucratic structures found in youth clubs and schools. Settling occurs when stable patterns of social relations are established around routines which ensure order and predictability about life situations. Two kinds of settling were identified, traditional and bureaucratic. The traditional kind involves conformity to existing patterns of how things are done, Youth Studies May 1991 otherwise he would have gone from one new venture to another without establishing any of them. This was not the case. Dave spent a lot of time and energy in establishing each new development. He saw as the key to this process the training and supporting of voluntary leaders who could take responsibility for the which have become routine and taken for granted over an extended period of time. For example, Steve's mornings were mainly taken up with "administration, writing and preparing reports and looking at the finances". In the evenings there were "hall activities - usually badminton and some discussion groups". Bureaucratic settling involves acceptance of a hierarchical structure of authority by the youth worker. An example of this occurred when Steve accepted that the District Youth Officer was the "immediate officer" to whom he was responsible and that he could move him to another position when things "weren't OK" with the school authorities at the time. On another occasion Steve thought the District Officer's concern about sending out agendas and meeting on time was "rubbish", but he admitted that he was "making sure that staff meetings are held regularly". There w ere also some occasions when youth workers sought to exert their authority, which they held by virtue of their formal position, over other leaders. An instance of this was when Steve sought to get his staff "to devise what their aims are as a team". He wanted to get something down in writing, but he had to admit that his staff had only "started to adopt one of the objectives" of another area team he had put before them. In this typology pioneering or settling type activities have been distinguished. But some activities of youth workers may best be described as pioneeringsettling. An instance of this was the development of a cell group structure within Dave's youth club. Dave formed new activities which became part of the youth club program. In this respect Dave showed he could undertake traditional settling activities as well as pioneering. His ability to move from one to the other, depending on the circumstances, suggests that his activities may be most appropriately described as pioneering-settling. cell groups in which leaders had "some small responsibility for a little group of people", because his own experience in youth groups had taught him that the ones that had "gone on" were those in whom "someone had invested a lot of life-sharing time in". Dave invested time and effort not only in pioneering the new structure but also in establishing it to the point where it became part of the traditional life of the club. In order to achieve this the key voluntary leaders were supported and trained by him and he encouraged them to care for their cell group members. The typology developed in this paper which has used Weberian ideas and applied them to the activities of youth workers, is still at a formative stage. Further examination of a wider range of examples of pioneering and settling under a variety of circumstances will assist us to understand how youth workers go about defining and achieving their goals in different social contexts. Reference Weber, M. 1964, The Theory of Social and Economic Organisation, The Free Press, New York. Neville Knight is a lecturer in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Caulfield Campus, Monash University, Melbourne. 55