Introduction to Contract Law - Real Estate Institute of Tasmania

advertisement

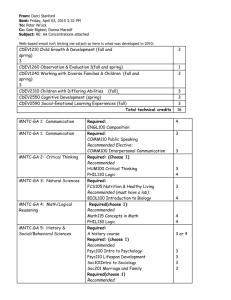

Introduction to Contract Law Introduction to Contract Law Acknowledgments Writer: Editor: Alicia Hutton, Mandy Welling Word processing & Graphics: REIT Professional Development Departments Version Number: 2 © 2012 The Real Estate Institute of Tasmania The REIT has issued this manual to a candidate enrolled with the REIT in the unit described in the title. This manual is for the use of that candidate only, to develop skills, knowledge and competence of that candidate, and the manual does remain the property of the REIT and is not to be reproduced in any way or transferred to any other person or used for any other purpose. This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the REIT. Disclosure Notice The material contained in this Unit is information/opinion of a general type. You should seek your own independent/expert advice in relation to any issues the subject of this Unit. The REIT is not a legal adviser. The REIT will not have liability for any loss/liability suffered/incurred by reason of any reliance on the content of this Unit. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 2 Welcome Welcome to “Introduction to Contract Law” which is one of the units in the Real Estate Institute of Tasmania’s Property Consultants’ and Assistant Property Managers’ Course. Unit outline and purpose This unit identifies some of the principles of Contract Law which will underpin your correct management of the contracts with clients and customers for which you are responsible. These contracts will include: The Sole Agency Agreement The Exclusive Property Management Agreement The Contract for Sale of Land The Residential Tenancy Agreement Specific Learning Outcomes Upon completion of this unit, you will be able to: Explain the requirements for the formation of a contract Identify contracts that may be void or voidable Explain the ways in which a contract may be terminated Instructions for Distance Learning Candidates Read through the learning manual; Complete all activities in this learning manual as you come to them; Check all answers to the learning activities from the back of the manual; Complete the set written assessment task, referring back to your learning manual where you need to; Submit the written assessment task to the REIT. Remember to keep a copy. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 3 Contract Law for Real Estate Welcome to Contract Law, this Chapter is designed to enable you to develop knowledge of the law of contract, so that you are able to recognise valid contracts and to indicate the options available where a contract does not meet these requirements. Much of the work to be covered will test your ability to apply general principles to the main contracts that you will encounter in your work in the real estate industry: ie the contract for sale of land, the residential tenancy agreement, the sole agency agreement and the exclusive property management agreement. Contract law is the basis of all business law and is concerned with the enforcement of promises. Having a sound knowledge of contract law will enhance your relationship with clients and enable you to provide a truly professional service in selling real estate which involves contractual arrangements between seller and buyer. We also hope that this Unit extends your basic knowledge and appreciation of this complex area of law and help you recognise the importance of knowing the limits of your legal knowledge, not exceeding those limits and advising clients when to seek legal advice. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 4 Chapter 1: Requirements for Formation of a Contract Definition A valid contract is an agreement made between two or more parties whereby legal rights and obligations are created which the law will enforce. Agreement An agreement involves two or more people thinking of the same thing. The elements of an agreement are an offer by one and acceptance of that offer by the other. Creation of legal obligations All contracts are based on agreement; for an agreement to be a contract there must be an intention to create legal obligations. ie, there is an intention that the agreement will be binding on both parties, if one party refuses to carry out his or her obligations, a court can be asked to enforce the agreement. Enforcement at law The law will not enforce some agreements even though they are contracts, if those agreements are contrary to written law. An example is Section 36 of the Conveyancing and Law of Property Act (1884) which sets out the requirement that a contract for sale of real estate must be in writing. A court would generally uphold statutory requirements (the written law). Classification of contracts Formation of a contract A contract is formed when two or more parties agree to do something enforceable by law. Not all contracts need to be in the form of written and signed agreements. The matters agreed upon by the parties are the terms of the contract. When all the terms are expressed, either by spoken word or in writing, an express contract is formed. Contracts can be formed from an intention to be implied from the conduct of the parties. Example: In the supermarket A customer takes a product from the shelf, goes to the cashier and pays for the product. No words are spoken, but the intention to make a contract can be implied from the conduct of the parties. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 5 Formal Contracts The law will sometimes require the terms of a contract to be expressed in a particular, formal manner. These include: contracts of record, which can be enforced by a court even if that is not the wish of all parties – eg, court judgements In Tasmania it is standard practice that a signature to a contract is witnessed by an independent person. This is not a strict legal requirement but is done so that an independent person can be called on at a later date to corroborate the execution of the document by the person whose signature has been witnessed. Simple contracts All contracts could be under seal if the parties wished. Most people prefer to form contracts in the simplest way that is still safe. This Chapter concentrates mainly on simple contracts. Any contract which is not a formal contract is a simple contract, whether written, verbal or implied. Where contracts are of importance, terms should be in writing. This enables both parties to fully understand and appreciate their rights and obligations. The important essential in all simple contracts is that "valuable consideration" must be present. That is, there is a gain or benefit to the person making the promise. This is not needed in a formal contract. The six elements of a valid contract Before a court will enforce rights and obligations which arise from an agreement, unless the six essential elements of a contract are present. Where all elements are present, then there is a valid contract. However, if one or more of the elements is absent, the contract may be classed as void, voidable, unenforceable or illegal. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The intention of the parties to create a legal relationship; An offer by one party and an acceptance by the other party; The presence of form or valuable consideration; The legal capacity of the parties; Genuine consent of the parties; The legality of the objects of the contract. The remainder of this chapter analyses the first three requirements. The other three requirements will be discussed later in this Unit. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 6 Intention to create legal relations To make an agreement enforceable at law, the parties must show an intention to create legal relations, either in writing or by actions that show intent which can be inferred by a court. The law presumes that agreements concerning family, friendship and social matters are generally not accompanied by an intention to bind the parties legally. It is possible for the parties to expressly negate an intention to create legal relations. However, if an agreement is reached in business dealings, the court will, in the absence of express words, normally hold that legal relations were intended to be created. Rules relating to offers Business transactions can often be very complex, requiring a great deal of negotiation and renegotiation before the terms are concluded. For a contract to be valid, an offer must be made by one party and accepted by another. An offer is a proposal or expression of willingness to enter into an agreement. The offer needs to be made in fairly specific terms before the person to whom the offer is directed can accept it. If your friend says to you, "I'll sell you my car", you might be interested in the proposal. But you would probably also reply, "For what price?" Rules of offer. 1. the offer must be effectively communicated by the offeror (the person proposing it) to the offeree (the person being invited to accept it); 2. there must be an intention to act on the offer; 3. the offer may be to a specific person or to any person – eg reward advertisements; 4. an invitation to treat (or enter into negotiations) is not an offer; Note that in accordance with this, a vendor who offers a property for sale in the range $120$140,000.00 is not bound to sell the property at any price over $120,000.00. 5. an offer may be withdrawn at any time prior to acceptance; 6. an offer will lapse once the time specified for acceptance has passed or after a “reasonable” time. Note that an offer also lapses when a counter offer is made – eg Jo Smith, the vendor, crosses out Fred Brown’s $120,000 offer for his property and writes $125,000 instead. Fred’s $120,000 offer no longer stands. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 7 For Property Consultants the most important rules are 1, 5 and 6. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 8 Rules relating to acceptance Acceptance occurs when the party to whom an offer is made agrees to the offer. Acceptance may be made by word of mouth, in writing, or by conduct, but must be made in the manner specified in the offer, if one is prescribed. 1. Communication of acceptance The offer must be actually communicated, that is, brought to the knowledge of the other party. When acceptance is made in the manner indicated by the offeror it is deemed to be communicated even though it might not be to that person's knowledge. To accept an offer is to agree to that offer in the exact terms that it has been put to you. The acceptance may be the end result of a bargaining process, the stage at which the negotiations become legally binding. In law, acceptance by return mail takes place as soon as the letter containing the statement of acceptance is posted in the mail. This only applies when the parties contemplate that acceptance will be by mail (e.g., where the offer is by mail). In the case of facsimile machines and electronic mail, acceptance is deemed to have occurred only when the fax or the e-mail has been received. If the offer is made on condition that acceptance must be notified in a specified manner, then acceptance cannot take place in any other manner E.g.: communicating acceptance directly to an offerer’s solicitor. 2. The acceptance must correspond exactly to the offer To accept an offer you must agree to it in exactly the terms in which it is put to you. A qualified acceptance is actually a counter offer. A counter offer has the effect of making the original offer lapse. 3. An offer remains open to acceptance until it is withdrawn and usually cannot be withdrawn once it has been accepted If the person making the offer wants to withdraw the offer, he or she must communicate this withdrawal of the offer to the other party before the other party has accepted. Agency and Offer & Acceptance As Property Consultants you are engaged to act on behalf of the vendor in respect of the sale of real estate. In the area of the sale of real estate, a Real Estate Agent only represents the vendor (or purchaser) as the case may be. Consider the following: Can a Property Consultant accept an offer on behalf of a vendor? In most cases, no. Unless a vendor has given you very specific authority to accept an offer of greater than $X then you have © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 9 no authority to bind the vendor by accepting an offer. Instructions from the vendor should be sought. Is communication to a Property Consultant of the acceptance of an offer effective acceptance? Communication of acceptance of an offer to a Property Consultant will generally not be deemed communication to the vendor unless it was a term of the offer that acceptance could be indicated in that manner. Is communication of the withdrawal of an offer to an Property Consultant effective as a withdrawal of the offer? Communication of the withdrawal of an offer to a Property Consultant will not be effective communication of withdrawal until the withdrawal comes to the attention of the vendor. Note from the above examples the importance of a Property Consultant always ensuring that vendors are kept informed of all offers and withdrawals of offers. Presence of form or consideration Consideration or valuable consideration means the gain or benefit to the person making the promise, (the promisor), arising from some act or forbearance of the other party, (the promisee). Consideration in simple contracts Any contract that is not a formal contract (ie, those by deed or under seal) is a simple contract, whether written, verbal or implied. The important essential is that in all simple contracts a valuable consideration must be present. In some cases, the law requires these contracts to be in writing, and in other cases the law requires the contracts to be supported by evidence in writing. In contracts for the sale of land, contracts are required to be in writing (see Section 36 of the Conveyancing and Law of Property Act 1884. You should note that a promise to do something in six months time is sufficient consideration. Thus a promise to pay $150,000 in 90 days’ time, in return for a promise to transfer the title to a house at the same time, is valuable consideration. It is not a requirement for a valid contract that a deposit be paid. Summary This chapter has covered three of the essential elements in the formation of a contract. You should now be able to explain and apply the rules relating to: © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 10 Intention to create legal relations; Offer and acceptance (agreement); and Consideration. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 11 Chapter 2: Scope of Contracts This chapter is concerned with the material contents of a contract and how that content will be interpreted where there is doubt regarding the obligation imposed. Terms of a Contract Terms of a contract are all the relevant statements which set out the rights and obligations established under the agreement. A good rule of thumb is to put a contract into written form if the agreement is reasonably complex. You might later want to have some written evidence of the rights and obligations which have been created under that agreement. In interpreting a contract, the terms or contents of the contract are known as the express terms. Express and implied terms Those terms which are written down or have previously been agreed to verbally are clearly express terms. Sometimes an important aspect of the agreement later arises for question and the parties find that this aspect has not been clearly set out or written down. This raises a legal question concerning implied terms of a contract. Implied terms An implied term is one that has not been directly discussed but has rather been simply assumed by the parties at the time when they reached the agreement. The express terms of a contract may also need to be supplemented by the implication of terms to address contingencies not expressly covered by its provisions. A term will not be implied if it can be described as ‘essential’, ie, a term going to the heart of the agreement or a term required by statute, as the court will not impose a contract on the parties in order to save an agreement that, as a result of inadvertent omissions, is too uncertain to be enforced. Examples of Implication of Terms Timing of payment Without a term as to the timing of payment, a contract makes no sense and accordingly, a court would readily infer a term in order to give business efficacy to the dealings. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 12 By operation of Law A variety of terms can, and in some instances will, be implied by operation of Law. The Conveyancing and Law of Property Act implies into leases and mortgages certain terms if those terms are not already covered in the document. Representations versus terms A representation is a statement concerning fact or containing a description of the subject matter of the contract. That representation may constitute a term of the contract when it has the effect of making a promise which is meant to be binding on the party making it. An expression of opinion is not usually regarded as a term of the contract because it is no more than a tentative statement which is not backed by a promise as to its accuracy. eg. “This article I am selling is the best value anywhere” is merely an expression of opinion or sales pitch and is not a promise whereas an assurance in response to a specific question about a product is a representation – it could be interpreted as a guarantee. Conditions of contracts Once a statement is deemed to be a term of the contract and not a mere representation, the problem still remains concerning the amount of importance to be placed on that statement. Was it intended that the statement would stand as a fundamental aspect of the contract so that the contract could not exist without it? Or was it intended that the contract would still exist even though there would be a resulting partial failure of the agreement if the matters expressed in the statement were not fulfilled? In contract law the difference is often expressed as the difference between a condition and a warranty. Condition versus warranty Condition A condition is a term which is vital to the agreement. The non fulfilment of the condition would result in an outcome of the agreement which was totally different from that envisaged by the parties when they entered the agreement. The non performance of the condition will usually result in a breach of contract ie, failure to perform an obligation for which the innocent party may rescind the contract and claim damages. Eg: Failure of a tenant to pay the rent agreed in a Residential Tenancy Agreement. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 13 Warranty A warranty is a lesser term of the contract, the breach of which will not result in an outcome fundamentally different from that originally envisaged by the parties when they entered into the contract. The non-performance of a warranty will normally give rise to a right to damages. However, the contract will still be valid and enforceable. Condition precedent A condition precedent is one that must be satisfied before the contract can be said to exist. A common condition precedent in purchasing land is that the purchaser obtain finance and/or sell their existing house within a specified time of signing the contract. The effect of the condition precedent will depend upon the width the condition is shown to have. For instance, the whole contract could fail if a condition precedent is not met eg if a buyer fails to obtain finance, whereas in other circumstances the condition precedent may only affect a particular term or terms of the agreement. Where a contractual right or obligation is subject to a condition precedent, the onus of proving that the condition has been fulfilled is upon the party who intends to rely on the right or obligation. Condition subsequent By contrast with a condition precedent, an obligation or right which is terminated upon the occurrence of some event, is said to be subject to a condition subsequent, eg, if one of the parties becomes insolvent. Exemption clauses or exclusion terms An exemption clause is a term in a contract which attempts to limit the liability of one party for injury caused to another party. Doctrine of privity The common law doctrine of privity of contract provides that only the parties to a contract can sue or be sued on the contract. A person not a party to the contract cannot enforce or seek to enforce terms of the contract, even if the contract is for their benefit. Summary This chapter has described the various principles involved in determining the scope and nature of a contract, and other matters which have an impact on the obligations imposed by a contract on both parties. You should now be able to: Determine the terms of a contract; Explain the difference between express and implied terms of a contract; © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 14 Identify the difference between a term of a contract and a mere representation; Explain and identify the differences between conditions precedent and conditions subsequent; Identify the differences between conditions and warranties in a contract; Explain and apply the principles of privity of contract. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 15 Chapter 3: Void, Voidable and Unenforceable Contracts Introduction Having established that the first three elements of a contract are present, ie: The intention of the parties to create a legal relationship; An offer by one party and an acceptance by the other party; The presence of form or valuable consideration; and having determined the scope of the contract, it is now appropriate to consider whether there are any particular aspects of the contract which may affect its validity. Matters which may affect a contract's validity include: A mistake by one or both of the parties (the contract may lack some formal requirement; Misrepresentation by one of the parties. One or both of the parties may have been induced or influenced to enter into the agreement by factors which operate to vitiate (make suspect) their consent; Illegality (the objects of the contract may infringe a rule of common law or statutory provision or may be contrary to public policy); Incapacity by one of the parties (the parties who entered into the agreement may not have had the necessary power to do so). Consequence of defects These defects produce varying consequences which may render the contract void, voidable or unenforceable. Void A void contract is not a contract at all because one of the essential elements in missing. In the case of a void contract for the sale of land, the Vendor would retain ownership of the property, and the parties are treated as if the agreement was never entered into. Voidable © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 16 A voidable contract can be affirmed or repudiated at the option of either of the parties. Such a contract is valid until steps are taken to repudiate it, and any action taken up to the time of repudiation is valid and effective. Eg, a contract entered into by minors. Unenforceable An unenforceable contract is valid, with legal consequences arising to the extent that it has been performed. However, it cannot be enforced in the courts because it is technically deficient eg, a verbal contract for sale of land is deficient because statute requires it to be in writing. Thus, where there is an unenforceable contract, neither party is able to sue to enforce it or to recover damages for breach of it. If a contract is unenforceable, it can still function to do certain things, for example, transfer title to property from one party to another, with the result that the Purchaser can effectively transfer title to a third party. This is not possible if the contract is void. Illegal If the purpose of the contract is illegal, the courts will not assist either of the parties to enforce the contract. The remainder of this Unit examines the features of these types of contracts. Matters affecting a contract’s validity Legal capacity of the parties The fourth essential element of a contract is the legal capacity of parties. With some exception, every person normally residing in Australia has the right to enter into contracts, to enforce those contracts and be bound by the contracts they make. Exceptions to full capacity The following classes of person under the law do not have full capacity in all cases to enter into valid contracts on all matters. Aliens; Minors; Persons of unsound mind and intoxicated persons; Bankrupts; Corporations; Imprisoned persons. Aliens © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 17 An alien is a foreigner who is not an Australian subject. In peace time, an alien has full capacity to enter into most contracts. In time of war, aliens who owe allegiance to an enemy country become enemy aliens and are restricted in their power to contract. Foreign sovereigns and their diplomatic staff in Australia are a special class of alien. They may enter into contracts, and enforce them, but they cannot be sued unless they submit themselves to the jurisdiction of Australian courts. Minor A minor is a person under the age of 18 years. A minor's capacity to contract is governed by common law rules and statutes which vary in some states. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 18 Contracts with minors are can be: 1. Valid and enforceable, eg: Contracts for supply of necessaries (such things as food, clothing, education); contracts made for the minor's benefit (eg agreements relating to services to provide the minor with means of livelihood, contracts for education or a contract of apprenticeship) 2. Voidable at the option of the minor: (a) Those binding unless repudiated by the minor during their minority or within a reasonable time after attaining the age of 18 years. This rule applies where the minor acquires an interest in contracts of a permanent nature including leases of land. (b) Those not binding unless ratified (approved) by the minor within a reasonable time of attaining the age of 18 years. These contracts are not of a continuing nature. 3. Unenforceable Persons who are of unsound mind or intoxicated A contract with a person who is of unsound mind or intoxicated is, prima facie, binding upon that person unless he/she can show that: At the time of making the contract, their mind was so affected as to be incapable of understanding what he/she was doing; and The other party was aware of his/her condition. If the impaired person can prove these points the contract is voidable at the option of the impaired person. This option to repudiate must be taken within a reasonable time of becoming sane or sober. Should the impaired person ratify the contract upon becoming sober or sane, that person cannot later repudiate the contract on the grounds of unsound mind or intoxication. Bankrupts Bankruptcy in itself does not make a person incapable of entering into contracts, but restrictions are placed upon that person by statute when dealing with other parties. Corporations A corporation (company) is an artificial body created by law which has separate existence to that of the individual(s) comprising it. A corporation has limited capacity to contract, depending on how it was formed and for what purpose. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 19 Imprisoned persons In most states, a convicted person cannot make a valid contract, nor enforce one that's already been made, during his/her time in prison. However, a contract that was made before their sentence may be enforced by a person appointed by the Crown. Genuine consent The fifth essential element of a contract is genuine consent of the parties. A consent which has been induced by fraud, or misrepresentation, or obtained through a mistake of fact, is not considered in law to be genuine. However, this does not mean that the law will regard the contract as being invalid. Mistake Mistakes can be classified as mistake of law and mistake of fact. Generally a mistake of law will not affect the contract as the legal maxim "ignorance of the law is no excuse" presumes everyone knows the law. If through ignorance of law a mistake is made in forming a contract, the party making the mistake will have to suffer any loss arising. If a party makes an error or mistake in judgement, such as believing the value to be greater that the contracted value, that party cannot escape the liabilities of the contract. The law will come to the aid of the parties only in certain classes of mistakes. Fraudulent misrepresentation Representations are statements made by one party to another during negotiations, prior to the formation of a contract. If the representation proves to be untrue, it is said to be a misrepresentation, which may be fraudulent, innocent or negligent. Fraud exists when it is shown that a false representation has been made: knowingly; or without belief in its truth; or recklessly, careless as to whether it be true or false. In order to constitute grounds for an action for fraud, the presence of each of the following six elements is necessary. 1. The representation must be one of fact; 2. The representation must be untrue; 3. The representation must be made with knowledge of its falsehood or without belief in its truth; © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 20 4. The representation must be made with the intention that it should be acted upon by the injured party; 5. The representation must actually deceive and be acted upon by the other party; 6. The person claiming (called the plaintiff) must have suffered damages. Fraud may exist where there is a partial statement of fact which changes the truthfulness of what has been said. Remedies for fraudulent misrepresentation Where fraud is present in a contract, the contract is voidable at the option of the injured party. The injured party may: Elect to have the contract completed and bring an action for damages or loss; Have the contract rescinded, with or without claiming damages; Successfully defend any action brought to enforce the contract. Innocent misrepresentation Innocent misrepresentation may be defined as an incorrect statement of fact made without intention to mislead and without knowing the statement to be false. This type of misrepresentation usually occurs through non-disclosure of facts without the intention to deceive the other party. Innocent misrepresentation renders the contract voidable, not void. The injured party has the right to: Rescind the contract and have it set aside; Refuse further performance of the contract. The injured party cannot as a general rule, sue for damages except: Where the innocent misrepresentation was made negligently and a confidential relationship existed between the parties, such as solicitor and client; Where an agent believes authority to perform certain acts exists, when in fact no such authority exists - the agent may be sued for breach of warranty of authority; Where a company prospectus contains incorrect statements of material facts. The Commonwealth Trade Practices Act 1974 provides, in certain circumstances, additional remedies to enable a person to recover loss where misrepresentation has arisen in connection with the supply of goods or services, or the sale or grant of an interest in land by a company. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 21 Negligent misrepresentation If a person with special skills or expertise provides advice to another person, either freely or for reward, that person must take reasonable care and skill with the accuracy of that advice or information. If there is a failure to take this reasonable care and a loss is suffered by the other party, then the person providing that advice is liable for damages for negligent misrepresentation. Legality of the objects The final essential element of a contract is the legality of the objects. If the object of the contract is one which is not allowed, or is discouraged by law, the contracts may be illegal at, common law or statute law. Contracts illegal at common law There are a number of contracts that can be illegal at common law. These contracts may involve an illegal act or an act contrary to "the public interest". There are several main classes of contracts illegal at common law; those most likely to affect a real estate sales person in their completion of a contract are: 1. Agreement to commit a crime or civil wrong 2. Agreements involving a conflict of interest with duty Should an employee or agent allow their interest, financial or otherwise - to interfere with duty, this interest would be considered to be illegal and therefore void. 3. Agreements tending to injure the public service These are agreements to procure titles or agreements with a person holding an official position, to use that person's influence, to obtain a benefit for the other party. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 22 4. Agreement in restraint of trade Eg, contracts which restricts one party from freely exercising that person's trade, business or profession. The Property Consultant may only need to be aware of these in relation to the sale of businesses. Many kinds of anti-competitive agreements are now regulated by specific Commonwealth and State Acts such as the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Commonwealth). Contracts illegal by statute law Certain statutes have provisions that affect business activities. Some statutes have provisions that absolutely forbid contracts of certain kinds, and others provide that they must conform with a certain form laid down in the Act eg a Residential Tenancy Agreement requiring a security deposit (bond) of the equivalent of two months’ rent is illegal under the Residential Tenancy Act. Effect of illegality The general effect of illegality in the formation of a contract is to render that contract void. If the contract is partly illegal and partly legal, and the illegal section can be separated from the legal section, the latter stands and can be enforced. Otherwise, the whole contract will be void. The general rule is that any money paid under an illegal contract is non-recoverable. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 23 Summary This chapter has been concerned with those matters which may affect the validity of a contract. You should now be able to: Explain the differences between valid, void, voidable and unenforceable contracts; Indicate the effect of contracts entered into by minors and intoxicated persons; Explain the meaning of mutual, unilateral and common mistake; Explain the effect of fraudulent and innocent misrepresentation; Identify the effect of contracts, which are illegal. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 24 Chapter 4: Termination, Discharge and Remedies A contract may be terminated in any one of the following ways: 1. by performance; 2. by agreement; 3. by frustration; 4. by operation of the law; 5. by breach. Types of Termination Termination by performance When the parties to the contract have performed their obligations under that contract, the contract is discharged. Performance may be by: actual performance; tender or attempted performance. Actual performance The normal way to discharge a contract is for the parties to discharge their obligations under a contract, the performance being within the terms of the agreement. Where the contract is to be completed by the payment of money, the money must be paid to the right person, at the proper place, at the proper time and in legal tender, unless otherwise agreed. Payment in legal tender constitutes an absolute discharge of the debt. If payment is made otherwise than by legal tender for example, by cheque or bill of exchange the debtor only obtains a conditional discharge. Should the cheque or bill of exchange be dishonoured then, in the absence of an express agreement to the contract, the original debt is revived. Payment by post Should a creditor request a debtor to forward payment by post in satisfaction of a debt, the debtor is discharged from liability by posting the payment, even if the letter containing that payment is lost. However, if the payment was by cheque and no claim was made on the debtors bankers, then the debtor would not be discharged as that person has not met the obligation. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 25 Unless the creditor expressly requests the payment to be sent by post, the debtor will not be discharged by posting the payment if it is not received by the creditor. Tender or attempted performance Tender is the attempted performance of the terms of the contract. It may be an offer of goods, services or money according to the circumstances of the contract. However, where a party refuses to accept the tender of money, the debt itself is not discharged, but the debtor is released from the duty to seek out the creditor again. The debtor must still be willing to pay the debt. Tender, to be a valid performance, must observe exactly any special terms which the contract may contain as to time, place and mode of payment. Termination by agreement A contract is the result of an agreement. The parties to a contract may, at any time, terminate the contract by a further agreement. This further agreement can be made in two main ways: By varying the terms of the original agreement by substituted agreement; By cancelling the original agreement, for example by waiver or release. Substituted agreement A new agreement may be made varying the terms of the original agreement so that a new contract is substituted for the old one. An example of a substituted agreement is that of novation. Here, one contract is rescinded and replaced by a new one under which the same rights and obligations as in the original contract are performed by different parties. So a new contract is substituted for the previous contract under which outstanding obligations of one party are taken over by another party now responsible for satisfying those outstanding obligations. Cancel by waiver Where the contract has not been performed by both parties, they may agree that the unfilled promises be waived. The consideration for the agreement is a mutual abandonment of rights, and rescinds the contract. Cancel by release Where one party has performed his/her obligations and the other party has not, the only method of discharging the contract is by agreement under seal to release the defaulting party, or the party still under obligation may give some further consideration for their release from the contract. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 26 It is possible that the contract itself contains provision for the discharge of the contract in certain circumstances. This provision can fall into two main groups: option to terminate (eg if one of the parties breaches the agreement); conditions subsequent. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 27 Termination by frustration After a contract has been formed, some unforeseen event may occur, rendering the contract impossible of performance. Examples where frustration has acted as a discharge of the contract: (a) When performance of the contract becomes illegal through a change in the law; (b) If a material thing vital to the performance of the contract is destroyed. For example, a building is hired for a future date but burns down in the meantime; (c) Where the contract is of a personal nature and the death or serious illness of one party makes the performance of the contract impossible; (d) When a particular event or specific set of circumstances is essential to the performance, and that event or circumstances does not eventuate, the parties are discharged; (e) When the performance of a contract would be impossible or radically different, because of government interference such as in times of war; (f) When supervening circumstances make performance of the contract impossible within the set time in the manner agreed in the contract. If performance becomes impossible through no fault of the parties, their contractual obligations are automatically discharged at the point of frustration. Thereafter neither can demand further performance by the other. Effect of frustration When the doctrine of frustration applies, the contract automatically comes to an end at the point at which the frustrating event occurs. Thereafter, neither party can be held to performance. However, the contract only terminates as and from the point of frustration rights, duties and liabilities which have accrued prior to that point remain on foot. Termination by law A contract may be discharged independently of the wishes of the parties. There are rules of law which will discharge a contract in certain circumstances. Merger © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 28 A simple contract is discharged by a deed made between the same parties dealing with the same subject matter. The lower form of contract is said to "merge" into the deed. Bankruptcy Should a party to a contract become a bankrupt pursuant to Commonwealth Bankruptcy Act 1966, that person is released from obligations under the contract. If the other party is owed money under the contract he/she may claim the debt as a creditor in the bankrupt's estate. In no case is the bankrupt released from liability incurred by that person for such things as fraud or a fraudulent breach of trust committed by that person. Material alteration Where one party to a contract makes a material alteration to the terms of a written contract without the consent of the other party, the party benefiting from the alteration is prevented from maintaining any action under the contract. Termination by breach One party to a contract may fail to fulfil obligations under that contract. This breach of contract may entitle the other party to regard themselves as discharged from their obligations. But certain breaches of contract do not give the innocent party the right to regard the contract as at an end, but merely entitle that party to sue for damages. There are two possible situations to consider. Where one party repudiates the whole contract, whether by act or deed; Where one party breaches a term of the contract. Repudiation by one party Repudiation occurs in the following four ways. (a) By renunciation before the contract is due for performance. If one party to a contract says or implies that he/she will not carry out obligations under the contract, this is known as anticipatory breach. The other party may treat the contract as discharged and immediately sue for damages. (b) By renunciation during the performance. Where there has been some performance of the contract and one party repudiates and will not complete their obligations, the other party can treat the contract as no longer binding. They are then entitled to sue for breach of contract. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 29 (c) By impossibility created by one party before the contract is due for performance. It is a rule of law that a person cannot by their own act rid himself/herself of obligations under a contract and thereby avoid liability. An example of this rule could be the sale of goods before the date of performance under the contract. (d) By impossibility created by one party during performance. Where one party to a contract renders the contract impossible of further performance during its performance, the innocent party has the right to sue for damages. Contracts broken by one party A breach in performance usually does not involve a complete and conscious repudiation of the whole contract, but a breach of obligation under that contract. Whether the breach is so basic as to entitle the other party to repudiate or whether that party is bound to regard the contract still on foot and is merely entitled to sue for damages is a difficult question. It will depend upon the term that has been breached. Remedies There are a number of remedies available for breach of a contract. Where the breach discharges the contract Certain breaches entitle the party not in default to regard himself/herself as freed from the obligation to perform his/her side of the contract. In such a case, that party may: (a) decide to keep the contract on foot and perform his/her part; (b) refuse to perform his/her part of the contract; (c) resist any action brought by the defaulting party; (d) take action against the other party for damages sustained due to the breach; (e) take action against the offending party for an amount equivalent to the value of goods and services provided. Where the breach does not discharge the contract This can occur when either: (i) the breach does not entitle the innocent party to regard the contract as at an end; or (ii) although entitled to do so, the innocent party has decided not to accept the guilty party’s repudiation. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 30 In such situations, the party not in default may: (a) Sue for specific performance Specific performance is an order of a court directing a party in default to specifically carry out obligations under the contract. This remedy will only be available in cases where damages will not provide adequate compensation for the breach of contract. It is applicable for contracts involving the sale of land. (b) Obtain an injunction An injunction is a court order restraining a person from doing a wrongful act or the repetition of a wrongful act. (c) Sue for damages An award of damages for breach of contract is to compensate the injured party with a sum of money for their loss resulting from the breach. If in fact the innocent party has sustained no loss from the breach, nominal damages may be awarded recognising that a legal right has been infringed. Where that party has sustained a loss, they could be entitled to substantial damages. Statutes of limitation State statutes limit the period in which legal action may be taken to enforce the right under a contract, depending on state legislation and the class of contract. For example for a specialty contract (deed) the period is 12 years in Tasmania and for simple contracts the period is generally 6 years. In certain circumstances the time to take action may be extended. Summary We have now seen that there are a number of reasons a contract may be terminated. The five ways in which a contract may come to an end are by performance, by agreement, by operation of law, by frustration and by breach. If there has been a breach of contract, then the innocent party has a number of remedies available to him or her. The most important of these are damages, specific performance and injunction. © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 31 Section review In this section, the material has covered the essential aspects of a contract, including: the essential elements for the formation of a contract; the principles regarding the interpretation of contracts; matters which may affect the validity or enforceability of a contract; ways in which a contract may be discharged; the remedies available for breach of contract. If there are any issues which are unclear, you are advised to consult one of the textbooks listed below. References Graw, Stephen, Introduction to the Law of Contract, 1993, Law Book Library Gillies, Peter, Business Law, Federation Press Barron, M.L., Fundamentals of Business Law, McGraw Hill Halsburys Laws of Australia © REIT Version 2 - 2012 Intro to Contract Law Manual 32