Management of Embedded Foreign Body: Penetrating Stab Wound

advertisement

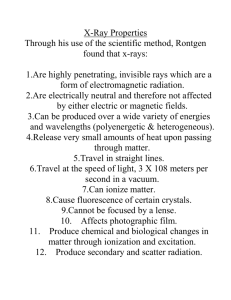

CA S E S T U DY Management of Embedded Foreign Body: Penetrating Stab Wound to the Head Sharolyn Martin, BSN, RN, CEN Glenn H. Raup, PhD, MSN, RN, NE-BC George Cravens, MD, FACS Carrie Arena-Marshall, MSN, RN, NE-BC ■ ABSTRACT Penetrating craniocerebral trauma is an injury in which a projectile violates the skull but does not exit. The significance of penetrating injuries to the head depends largely on the circumstances of the injury, the velocity of impact, and attributes of the projectile. While most penetrating head injuries are caused by firearms, lower-velocity mechanisms of penetrating brain injury present unique challenges for the multidisciplinary team involved with the delivery of care. Appropriate management can lead to optimal outcomes and limit secondary brain injury. ■ KEY WORDS Embedded foreign body, Multidisciplinary approach, Penetrating embedded trans-cranial trauma (PETT) P enetrating embedded trans-cranial trauma (PETT) is an injury in which a projectile violates the skull but does not exit. These types of injuries may be caused by bullets or other sharp objects. Penetrating head injuries may be the result of interpersonal violence, suicide attempts, falls, motor vehicle crashes, or occupational incidents. The significance of penetrating injuries to the Sharolyn Martin, BSN, RN, CEN, is Emergency Department Research Nurse, JPS Health Network, Fort Worth, Texas, Glenn H. Raup, PhD, MSN, RN, NE-BC, is Assistant Professor, DNP Program, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas, George Cravens, MD, FACS, is Chairman of Neurosurgery, JPS Health Network, Forth Worth, Texas, and Carrie Arena-Marshall, MSN, RN, NE-BC, is ICU/RDU Manager, JPS Health Network, Fort Worth, Texas. Corresponding Author: Sharolyn Martin, BSN, RN, CEN, 1575 S Main, Ft Worth, TX 76104 (Smartin01@jpshealth.org). 82 Journal of Trauma Nursing • Volume 16, Number 2 head depends largely on the circumstances of the injury, the velocity of impact, attributes of the projectile, and the location combined with the intracranial path of the object. The focus of this article is on the management of nonballistic PETT. Management of a penetrating injury as a result of a transcranial embedded foreign object may appear straightforward, but unique issues such as formation of a traumatic pseudoaneurysm, vascular disruption with sudden exsanguination, limited visualization of cranial contents on computerized tomography (CT) scan secondary to artifact from the impaled object, and the development of infectious complications greatly limit the establishment of universal treatment algorithms to treat victims of transcranial trauma. ■ CASE REPORT A 21-year-old Hispanic man was stabbed in the head with a large butcher knife during an altercation at a bar. He arrived at the hospital via emergency medical services with the knife blade firmly embedded in his left temporal bone just superior to the zygomatic arch. A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15 was maintained during transport as well as in the hospital. He denied any loss of consciousness during the assault. The only deficit noted during his primary and secondary assessments in the emergency department was a probable injury to his left eighth cranial nerve, demonstrating difficulty with closure of his left eye. After completion of the physical assessment, a skull radiograph was taken (Fig 1). This radiograph revealed the knife blade to be projecting over the left orbit and extending into the left temporal fossa. No definite fractures were appreciated. A CT scan of his brain was performed emergently. The CT demonstrated a large knife blade embedded within the left skull traversing along the posterior aspect of the left orbit within the anterior aspect of the left middle cranial fossa, with the tip of the blade resting near the cavernous portion of the left carotid artery. No conclusive evidence of an associated intracranial or extra-axial hemorrhage was noted. Extensive artifact obscured the surrounding soft tissues (Fig 2). April–June 2009 FIGURE 1. Plain skull radiograph-embedded transcranial foreign object. Arteriography of his cerebral arteries was obtained, because of the proximity of the blade tip to the left carotid artery, to determine the extent of cerebrovascular injury. The angiogram revealed no evidence of an intimal injury, pseudoaneurysm, or extravasation, showing normal bilateral internal carotid and cerebral arteries (Fig 3). Upon completion of all the necessary diagnostic studies, he was taken to the operating room where he underwent a left frontotemporal craniotomy with a craniotome. After the bone flap was removed, careful elevation and identification of the foramen ovale, foramen rotundum as well as the superior orbital fissure was performed. After all structures had been identified, a 270 elevation of the dura mater around the knife was attained. Dural bleeding from around the cavernous sinus as well as a dural tear was noted in the anterior portion of the temporal lobe. Dead tissue from the brain was then carefully suctioned away, and the wound was FIGURE 3. Standard cerebral angiogram without evidence of vascular injury. FIGURE 2. CT scan demonstrating extensive artifact from embedded knife. irrigated with an antibiotic solution. The knife was then removed cautiously by pulling in the same trajectory as it had been inserted. After the knife was removed, bleeding was selectively controlled with bipolar electrocautery and with gelfoam with thrombin. After approximately 5 minutes of direct surveillance of the cavernous sinus region, no signs of excessive bleeding were noted from the vessels in the area. Therefore, the area was rinsed with antibiotic irrigation, and the dural tears were repaired. The bone flap was replaced and then the pericranial flap, temporal fascia, and skin were properly positioned and the layered closure was completed. The surgical procedure was tolerated well. The patient was allowed to awaken from the general anesthesia in the operating room. He was taken immediately for a postoperative CT scan and then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close observation. He underwent 1 additional postoperative CT scan; neither of the follow-up scans showed any signs of active intracranial bleeding. He was discharged on postoperative day 3 without incident. He did not return for his follow-up appointment. Because this injury resulted from an act of violence, the surgical team was also responsible for the proper handling of forensic evidence. Once the knife was removed from the cranial vault, a chain of evidence had to be established and maintained. This was accomplished by wrapping the knife in a towel of the operating room and placing it in a large envelope, sealing it with patient stickers that had been timed, dated, and initialed, across the seams. This envelope also cautioned that a sharp object was enclosed inside for personnel safety. Appropriate chain of evidence forms were completed and attached to April–June 2009 Journal of Trauma Nursing • Volume 16, Number 2 83 the outside of the envelope before it was dropped in the evidence collection safe. The appropriate law-enforcement agency was notified for later retrieval of the knife. ■ DISCUSSION PETT comes with specific issues not associated with blunt traumatic brain injury. This article does not attempt to discuss the overall treatment of traumatic brain injury such as managing increased intracranial pressure; instead, it will present information particular to penetrating head injuries. The scope is narrowed further to look at treatment modalities as well as emergency, perioperative, and intensive care nursing for nonballistic penetrations that encompass retained transcranial foreign objects. Intracranial stab wounds are atypical, secondary to the effective barrier provided by the adult skull. Nonmissile penetrating craniocerebral injuries are generally easier to treat than missile injuries. A stab wound creates a fine hemorrhagic infarction that typically confines brain damage to the wound tract.1 Nonballistic penetrating head trauma tends to occur at a lower velocity, which often causes vital structures to be shifted aside rather than obliterated.2 The prognosis for nonmissile PETT is good in the absence of a laceration to one of the major intracranial blood vessels with development of a subsequent massive intracerebral hematoma or direct injury to the brainstem. The usual areas of penetration are in the locality of the orbits or in the temporal areas where the skull is thin.3 Temporal stab wounds are prone to major neurological impairment as a result of the delicacy of the temporal bone and the close proximity of vital structures and vasculature of the brain.4 Morbidity and mortality tend to be higher from temporal stab wounds secondary to the aforementioned reasons. Emergency nursing considerations The initial evaluation of an individual who has sustained a transcranial injury should consist of a very thorough physical examination as well as radiographic studies and laboratory tests. The primary survey, assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulatory status, is always the foremost concern when dealing with PETT. After ensuring patency and clinical stabilization of the physiologic components of the primary survey, a meticulous neurological examination should be performed. A detailed assessment should address the level of consciousness including documentation of the GCS, overall mental status, cranial nerves, and motor/sensory function. A comprehensive head-to-toe assessment should follow, assuming that the patient is physiologically stable, evaluating all other systems. Specific attention should be given to evaluation of the scalp. Oftentimes the penetrating 84 Journal of Trauma Nursing • Volume 16, Number 2 object is absent at the time of assessment. Penetrating wounds do not have usual sites or characteristic entry wounds and are often buried beneath blood-matted hair. Puncture wounds from objects such as ice picks are often minute and easily missed, causing a delay in diagnosis of a craniocerebral injury. Once physiologic stability has been ensured, laboratory and radiological evaluations are vital to determining the extent of injury. Initial laboratory evaluation studies should include an arterial blood-gas analysis, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, type and crossmatch, coagulation tests, and a drug screen including alcohol level. Radiographic assessment may consist of a CT scan, skull series, angiography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Computerized tomography scans can detect the path and location of the embedded foreign body, bone and metal debris fragments, intracranial damage and hematomas, and mass effect. While CT scanning is considered the gold standard for evaluation of intracranial injury,5 it may be significantly blighted when a penetrating metal object is embedded in the cranial vault. Because of the distortion, brain injury along the trajectory of the penetrating object may not initially be visualized. An immediate postoperative scan may be warranted to look for missed contusion brain injury or hemorrhage.6 CT scans are also necessary to evaluate any changes in a patient’s mental status. Angiography is advocated for initial evaluation of suspected cerebral vascular injuries caused by PETT and to evaluate postoperatively for the presence of a pseudoaneurysm. When ordering a diagnostic cerebral angiogram looking for initial vascular injury with an embedded metal object, it is important to specifically order a standard cerebral angiogram as opposed to a CT angiogram. In these cases, the standard angiogram allows for much higherresolution images because there is no artifact such as would be seen with the CT angiogram. Magnetic resonance imaging is contraindicated in the presence of metallic fragments as the magnet may cause movement of the projectile. A magnetic resonance imaging scan may provide more detailed information than a CT scan for penetrating nonmetallic foreign objects. Perioperative nursing considerations The most appropriate management for an embedded transcranial foreign object is to leave it in place until it can be removed in a surgical suite under direct visualization. Minimal manipulation of the embedded object prior to removal maximizes the preservation of cerebral function by avoiding additional tissue damage and sudden exsanguination if the object is tamponading a major vessel.7 Techniques employed to stabilize impaled objects consist of taping, wrapping with sterile towels, suturing in place, covering with a cup, and possibly cutting the April–June 2009 embedded object down in size to decrease the likelihood of accidental manipulation or removal.8 Embedded object removal may cause many problems, as any movement during disimpaction may lead to further tissue or vessel damage with increased neurological deficits. The individual may survive the initial injury, but removal itself can lead to death. The impaled object should be removed along its trajectory. Depending on the location of the largest portion of the object, the foreign body should be removed by either the antegrade or the retrograde route following the trajectory of entry.9 In PETT, the foremost purpose of surgery is to limit the possible complications that can arise immediately after the removal of the embedded object.10 If the patient is stable, it may be prudent to delay the surgical removal of the object in order for the arrested bleeding secondary to the tamponade effect to become consolidated and the injured vasculature can develop a firm clot.9 When deemed appropriate, the surgical procedure should be undertaken to remove the embedded foreign body and to débride necrotic tissue and clots followed by thorough hemostasis and dural closure. injury to the brain. Factors correlated with seizures consist of severity of injury, retained foreign debris, and hematoma formation.15,16 The neurological injury is thought to cause a hyperexcitability of neurons with a consequential formation of an epileptic focus. Anticonvulsant prophylaxis administered in the immediate postinjury period is believed to curb neuronal hyperexcitability and reestablish the seizure threshold.14,17,18 Specific nursing interventions Multiple concerns accompany victims of PETT in the post–foreign body removal period. The primary concern is the formation of a pseudoaneurysm. Rupture of traumatic intracranial aneurysm occurs within 3 weeks after the initial injury and carries a 50% mortality rate.11 As many of these lesions are not visible on initial arteriograms and have a high likelihood of future development, routine angiography should be performed 7 to 14 days postinjury on all patients.12 Another delayed complication is cerebral vasospasm. It characteristically appears within the first 2 weeks postinjury, principally days 5 through 11.11 If not treated promptly, the end result of either vasospasm or pseudoaneurysm rupture is decreased cerebral perfusion pressure. A continued state of cerebral hypoperfusion will cause tissue hypoxia and cellular starvation with secondary neuronal injury, which carries a very poor prognosis. Another customary complication that follows PETT is infection. Cerebrospinal fistulas, meningitis, and abscess are a few of the sources for infection. Bacterial contamination occurs in the wound as a result of dirt, bone fragments, or other foreign matter entering along with the embedded foreign object. Organic materials, including wood or bone, are more likely than inorganic projectiles, such as glass or metal, to fragment and become infected because of their porous nature.13 Additional latent infections may be composed of scalp infections, osteomyelitis, and cerebritis. Tetanus prophylaxis and antibiotics may avert these infectious complications.14 Posttraumatic epilepsy is relatively commonplace after PETT. Seizures are thought to arise secondary to direct Nursing interventions for patients with transcranial embedded foreign bodies may be categorized by the following: (1) patient’s self-image, (2) family/loved-one acceptance and perception, (3) physiologic management, (4) neurological function, and (5) multidisciplinary communication. The patient’s acceptance and adjustments to the traumatic injury are of great importance to obtaining the maximum level of recovery. Acceptance of disfigurement and physical limitation are considerable obstacles to overcome. Nurses, by not only caring for but also caring about their patients, initiate the healing process through their own acceptance of their patients’ appearance and physical condition. This course of action begins with the preparation of the patient of what to expect. Compassionate honesty in all communications is vital to establishing a trusting bond in the nurse-patient relationship. In cases involving victims of embedded transcranial objects, one of the most important details is making sure the family sees the patient, providing his physical condition permits, prior to the surgical procedure. Nurses with an expertise in dealing with this type of PETT recognize the possibility of adverse events, including significant changes in physical and neurological function and even death, occurring during the extrication procedure. The importance of the family seeing them just prior to the operation cannot be overvalued. The patient/family needs to be made aware of the possible complications involved during the procedure to remove the impaled object and be given the chance to discuss thoughts and feelings with each other as well as with a healthcare professional to answer questions. Nurses excel at this role because of their ability to see the big picture without losing sight of the smallest details. To be an effective steward for a patient who has an embedded transcranial foreign body, the nurse must not only possess the knowledge of appropriate nursing care of traumatic brain injury in general but also know the nuances of physiological monitoring and care associated with PETT, both nursing and medical. Nurses must be vigilant in reviewing all previous orders to ensure that they have been completed, in following up to be sure critical time-sensitive results have been posted, and in viewing current orders to be sure all the different disciplines April–June 2009 Journal of Trauma Nursing • Volume 16, Number 2 Intensive care nursing considerations 85 are working cooperatively. This will ensure quality care as it provides the foundation for recognizing even subtle changes in their patient’s physiological condition that can lead to secondary insult and further morbidity, if not addressed in a timely manner. Communicating with other team members in a clear, concise, and professional manner ensures an optimal chance for the best possible recovery. Reporting diagnostic results concerning physiological parameters unique to penetrating injuries, as well as, changes and responses to therapy is a continuum goal led by nursing. Understanding the divergence between blunt and PETT empowers nurses to bring different dimensions into patient care. ■ CONCLUSION Effective management of embedded transcranial foreign objects necessitates an understanding of the mechanism of injury and associated neurological pathophysiology. The individual may survive the initial injury but later succumb to death as a result of manipulation and/or surgical removal of the impaled object or from delayed complications such as the rupture of a pseudoaneurysm or development of an infectious process. Optimal outcomes for victims of PETT can be provided through a multidisciplinary approach incorporating medical, surgical, and nursing expertise. Nursing plays an integral role in ensuring the best possible outcomes for patients who have sustained transcranial trauma. Nurses’ role as patient advocates ensures consistency throughout the multidisciplinary continuum of care. REFERENCES 1. Dempsey L, Winestock D, Hoff J. Stab wounds of the brain. West J Med. 1977;126:1–4. 2. Paul S, Lee C. Trauma case review: survival following impalement. Crit Care Nurse. 1994;14:55–59. 86 Journal of Trauma Nursing • Volume 16, Number 2 3. Dooling J, Bell W, Whitehurst W. Penetrating skull wound with a pair of scissors: case report. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:636–638. 4. Kennedy U, Geary U, Sheehy N. Intracranial stab wound: a case report. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14:72–74. 5. International Brain Injury Association, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, et al. Guidelines for the management of penetrating head injury: neuroimaging in the management of penetrating brain injury. J Trauma. 2001;51(2)(suppl):S7–S11. 6. Lin H, Lee H, Cho D. Management of transorbital brain injury. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70(1):36–38. 7. Arashiro K, Kunihiro I, Nobuo F. Unusual facial impalement injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:145–147. 8. O’Loughlin M, Criddle L. A 79-year-old man with an impalement injury of his face. J Emerg Nurs. 2004;30:303–306. 9. Rao G, Rao N, Reddy P. Technique of removal of an impacted sharp object in a penetrating head injury using the lever principle. Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12(6):569–571. 10. Tanicioni F, Gaetani P, Pugliese R, Rodriguez Y, Baena R. Intracranial nail: a case report. J Neurosurg Sci. 1994;38:239–243. 11. Blissitt P. Care of the critically ill patient with penetrating head injury. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2006;18:321–332. 12. Amirjamshidi A, Rahmat H, Abbassioun K. Traumatic aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas of intracranial vessels associated with penetrating head injuries occurring during war: principles and pitfalls in diagnosis and management: a survey of 31 cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:769–780. 13. Miller C, Brodkey J, Colombi B. The danger of intracranial wood. Surg Neurol. 1977;7(2):95–103. 14. Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: infection prophylaxis. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(suppl 1):S26–S31. 15. Kennedy C, Freeman J. Post-traumatic seizures and post-traumatic epilepsy in children. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1986;1(14):66–73. 16. Lewis R, Yee L, Inkelis S, Gilmore D. Clinical predictors of post-traumatic seizures in children with head trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(7):1114–1118. 17. Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: antiseizure prophylaxis. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(suppl 1):S83–S86. 18. Kuhl D, Boucher B, Muhlbauer M. Prophylaxis of post-traumatic seizures. DICP. 1990;24(3):277–285. April–June 2009