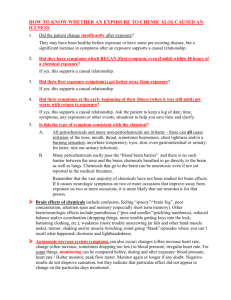

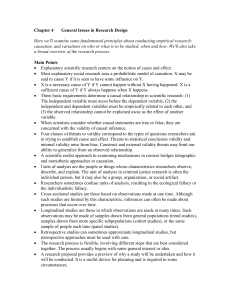

Confusion about Causation in Insurance

advertisement