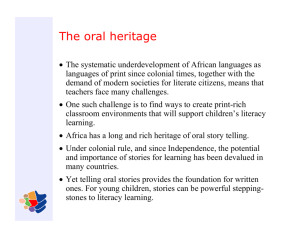

Research Proposal Colonial Concepts of Development in Africa. A

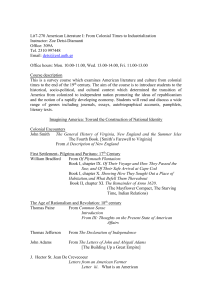

advertisement