Authority and Obedience in Bernhard Schlink's Der Vorleser and Die

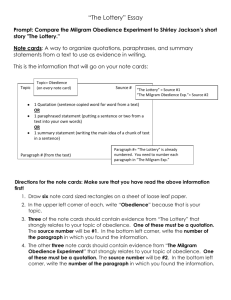

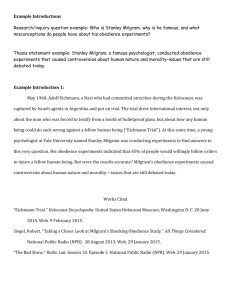

advertisement