umi-umd-2422 - DRUM - University of Maryland

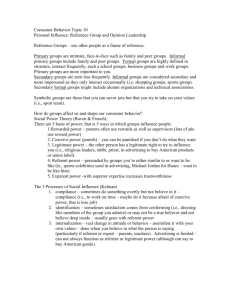

advertisement