FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT Docket Nos. 04-3953(L), 04

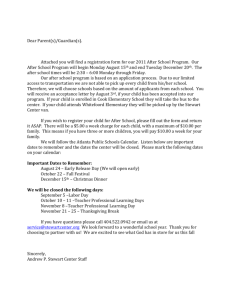

advertisement