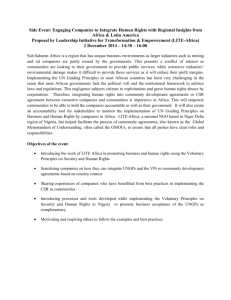

Not Always in the People's Interest

advertisement