Mark Lemley & R. Anthony Reese - Berkman Center for Internet and

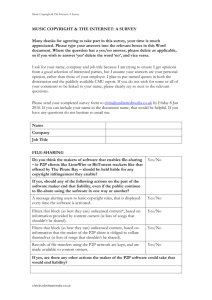

advertisement