Pastures for Profit - The Learning Store

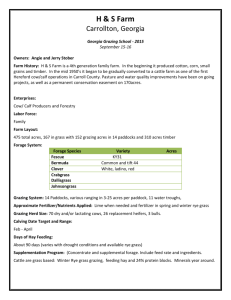

advertisement