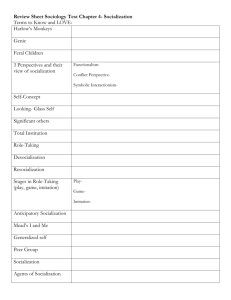

Organizational Culture: Elements, Functions, and Change

advertisement