modern trends in veterinary malpractice: how our evolving attitudes

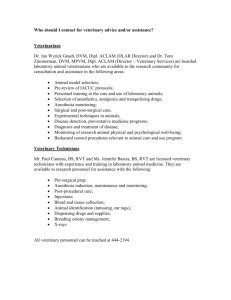

advertisement