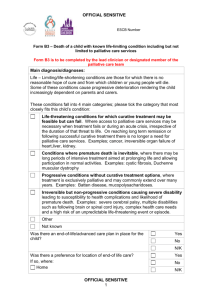

Guidelines for the Assessment of Bereavement Risk in Family

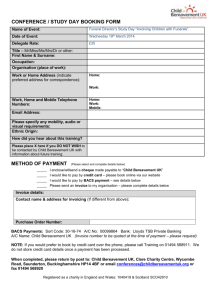

advertisement