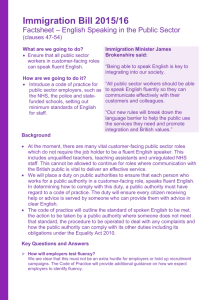

Analyzing and Improving Customer-Facing Processes

advertisement