In re Netsmart Technologies, Inc. Shareholder Litigation

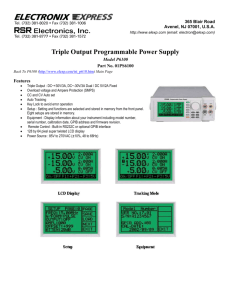

advertisement