Creating an Interprofessional Workforce

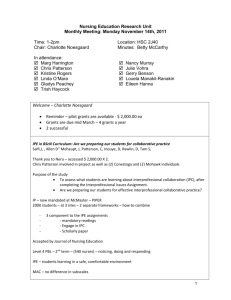

advertisement