The Instinct of An Artist - Rare and Manuscript Collections

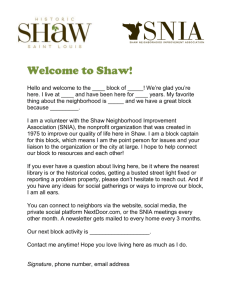

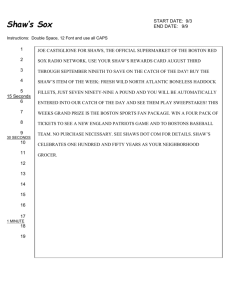

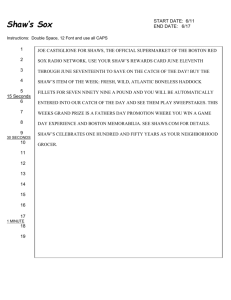

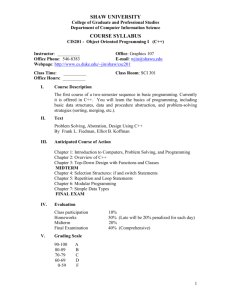

advertisement