Mrs. Warren's Profession - Roundabout Theatre Company

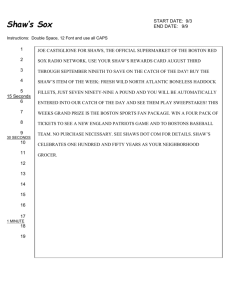

advertisement