in The Simpsons

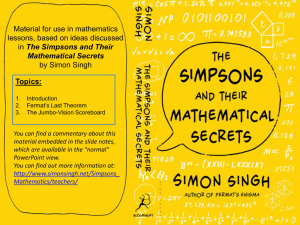

advertisement