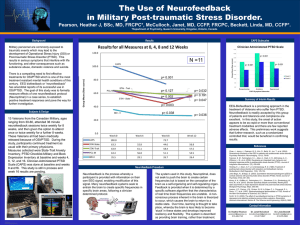

Remediation of PTSD Symptoms Using Neurofeedback

advertisement