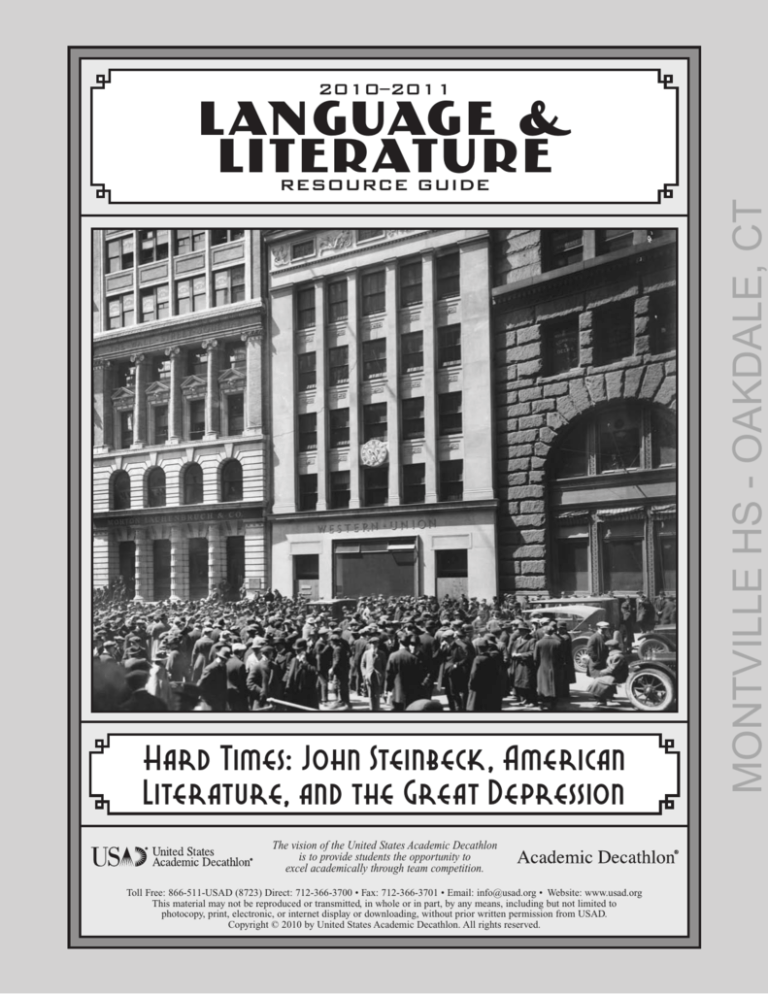

2010–2011

Hard Times: John Steinbeck, American

Literature, and the Great Depression

The vision of the United States Academic Decathlon

is to provide students the opportunity to

excel academically through team competition.

Toll Free: 866-511-USAD (8723) Direct: 712-366-3700 • Fax: 712-366-3701 • Email: info@usad.org • Website: www.usad.org

This material may not be reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, by any means, including but not limited to

photocopy, print, electronic, or internet display or downloading, without prior written permission from USAD.

Copyright © 2010 by United States Academic Decathlon. All rights reserved.

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

LANGUAGE &

LITERATURE

RESOURCE GUIDE

SEC T ION I:

Critical Reading. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

ONCE THERE WAS A WAR (1958). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

Life and Writing in the 1960s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

THE WINTER OF OUR DISCONTENT (1961). . . . . . . . .

25

TRAVELS WITH CHARLEY (1962) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

THE NOBEL PRIZE FOR LITERATURE, 1962. . . . . . . . . .

25

AMERICA AND AMERICANS (1966). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

Early Life and Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

THE ACTS OF KING ARTHUR AND

HIS NOBLE KNIGHTS (1976) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

Work Experience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

STEINBECK’S DEATH, DECEMBER 20, 1968. . . . . . . . .

26

SEC T ION II:

John Steinbeck and

the Grapes of Wrath. . . . . . . . . . 10

Introduction: Relationship to the Theme . . . . . . . . . . 10

John Steinbeck’s Life (1902–68). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Early Publication: Cup of Gold (1929). . . . . . . . . . 13

The Grapes of Wrath (1939). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

First Marriage, Family Life, and Friendship. . . . . 13

Historical Context:

The Great Depression in California . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Life and Writing in the 1930s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

THE PASTURES OF HEAVEN (1932). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

TO A GOD UNKNOWN (1933). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

Documentary Evidence of the

Great Depression in California . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

TORTILLA FLAT (1935) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

15

Literary History and the Novel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

IN DUBIOUS BATTLE (1936). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

Form and Structure of the Novel . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

IN DEPTH: OF MICE AND MEN (1937) . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

Characters. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

THEIR BLOOD IS STRONG (1938) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

TOM JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

THE LONG VALLEY (1938) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

MA JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

THE GRAPES OF WRATH (1939), FILM (1940). . . . . . . .

18

JIM CASY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

Life and Writing in the 1940s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

ROSE OF SHARON. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

THE FORGOTTEN VILLAGE (1941) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

PA JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

SEA OF CORTEZ (1941). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

AL JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

THE MOON IS DOWN (1942). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

JIM RAWLEY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

BOMBS AWAY (1942). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

UNCLE JOHN JOAD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

LIFEBOAT (1944). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

NOAH JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

CANNERY ROW (1945). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

GRANMA AND GRAMPA JOAD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

THE WAYWARD BUS (1947). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

RUTHIE AND WINFIELD JOAD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

IN DEPTH: THE PEARL (1947) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

MULEY GRAVES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

A RUSSIAN JOURNAL (1948). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

IVY AND SAIRY WILSON . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

Life and Writing in the 1950s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

FLOYD KNOWLES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

BURNING BRIGHT (1950). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

THE WAINWRIGHTS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

IN DEPTH: VIVA ZAPATA! (1952) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

CONNIE RIVERS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

IN DEPTH: EAST OF EDEN (1952). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

WILL FEELEY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

SWEET THURSDAY (1954) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

24

Setting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

THE SHORT REIGN OF PIPPIN IV (1957). . . . . . . . . . . .

24

THE DUST BOWL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Table of Contents

THE ROAD, HIGHWAY 66 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

CALIFORNIA, THE GARDEN OF EDEN. . . . . . . . . . . . .

40

THE BAKERSFIELD HOOVERVILLE CAMP. . . . . . . . . . .

40

THE WEEDPATCH CAMP. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

Selected Work: “Women on the Breadlines”

(1932) By Meridel Le Sueur. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

THE FLOOD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

“Women on the Breadlines”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

Style. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960) and

“The Gilded Six-Bits”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68

Literary and Historical Allusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Metaphor, Figurative Language,

Motif, and Symbolism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Selected Work: “The Gilded Six-Bits,”

(1933) by Zora Neale Hurston. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

“The Gilded Six-Bits”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Themes and Symbolism. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

William Faulkner (1897–1962) and “Barn Burning” . . 77

Contemporary Reviews of the Novel. . . . . . . . . . 50

Selected Work: “Barn Burning,”

From Novel to Film . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

(1938) by William Faulkner. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Conclusion: The Place of The Grapes of Wrath

in the Discourse of the Great Depression. . . . . . . . . . 52

“Barn Burning”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

Carl Sandburg (1878–1967) and The People, Yes. . . . 89

SEC T ION III:

Shorter Selections. . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Selected Work: Excerpt from

The People, Yes, (1936) by Carl Sandburg . . . . . . . . . 91

Introduction: Relationship to the Theme

and to The Grapes of Wrath . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

The People, Yes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Studs Terkel (1912–2008) and Hard Times:

An Oral History of the Great Depression. . . . . . . . . . 55

Selected Work: “The Song,” Interview with

Yip Harburg, from Hard Times: An Oral History

of the Great Depression by Studs Terkel . . . . . . . . . . 57

Langston Hughes (1902–67) and

“Let America Be America Again” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Selected Work: “Let America Be America

Again,” (written in 1936, published in 1938)

by Langston Hughes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

“Let America Be America Again”. . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Selected Work: “Cesar Chavez,” from

Hard Times: An Oral History of the

Great Depression by Studs Terkel. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

NOTES. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Hard Times. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

3

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Narrative Viewpoint. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Meridel Le Sueur (1900–96) and

“Women on the Breadlines” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

SECTION

I:

C

ritical reading is a familiar exercise to students, an

exercise that many of them have been engaged in

since the first grade. Critical reading forms a major

part (more than fifty percent) of the PSAT, the SAT, the

ACT, and both Advanced Placement Tests in English.

It is the portion of any test for which students can do

the least direct preparation, and it is also the portion

that will reward students who have been lifelong readers. Unlike other parts of the United States Academic

Decathlon Test in Language and Literature, where the

questions will be based on a specific works of literature

that the students have been studying diligently, the critical reading passage in the test, as a previously unseen

passage, will have an element of surprise. In fact, the

test writers usually go out of their way to choose passages from works not previously encountered in high

school so as to avoid making the critical reading items

a mere test of recall. From one point of view, not having

to rely on memory actually makes questions on critical

reading easier than the other questions because the

answer must always be somewhere in the passage,

stated either directly or indirectly, and careful reading

will deliver the answer.

Since students can feel much more confident with

some background information and some knowledge

of the types of questions likely to be asked, the first

order of business is for the student to contextualize the

passage by asking some key questions. Who wrote it?

When was it written? In what social, historical, or literary

environment was it written?

In each passage used on a test, the writer’s name

is provided, followed by the work from which the passage was excerpted or the date it was published or the

dates of the author’s life. If the author is well known to

high school students (e.g., Charles Dickens, F. Scott

Fitzgerald, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Jane Austen), no

dates will be provided, but the work or the occasion

will be cited. For writers less familiar to high school

students, dates will be provided. Using this information,

students can begin to place the passage into context.

As they start to read, students will want to focus on what

they know about that writer, his or her typical style and

concerns, or that time period, its values and its limita-

tions. A selection from Thomas Paine in the eighteenth

century is written against a different background and

has different concerns from a selection written by Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr. prior to the passage of the Civil

Rights Act. Toni Morrison writes against a different

background from that of Charles Dickens.

Passages are chosen from many different kinds

of texts—fiction, biography, letters, speeches, essays,

newspaper columns, and magazine articles—and may

come from a diverse group of writers, varying in gender, race, location, and time period. A likely question

is one that asks readers to speculate on what literary

form the passage is excerpted from. The passage itself

will offer plenty of clues as to its genre, and the name

of the writer often offers clues as well. Excerpts from

fiction contain the elements one might expect to find

in fiction—descriptions of setting, character, or action.

Letters have a sense of sharing thoughts with a particular person. Speeches have a wider audience and a

keen awareness of that audience; speeches also have

some particular rhetorical devices peculiar to the genre.

Essays and magazine articles are usually focused on one

topic of contemporary, local, or universal interest.

Other critical reading questions can be divided into

two major types: reading for meaning and reading for

analysis. The questions on reading for meaning are

based solely on understanding what the passage is saying, and the questions on analysis are based on how the

writer says what he or she says.

In reading for meaning, the most frequently asked

question is one that inquires about the passage’s main

idea since distinguishing a main idea from a supporting

idea is an important reading skill. A question on main

ideas is sometimes disguised as a question asking for

an appropriate title for the passage. Most students

will not select as the main idea a choice that is neither

directly stated nor indirectly implied in the passage, but

harder questions will present choices that do appear in

the passage but are not main ideas. Remember that an

answer choice may be a true statement but not the right

answer to the question.

Closely related to a question on the main idea of

a passage is a question about the writer’s purpose. If

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

4

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Critical Reading

the opposite of what it is. With each of these methods

of irony, two levels of meaning are present—what is said

and what is implied. An ironic tone is usually used to

criticize or to mock.

A writer of fiction uses tone differently, depending

on what point of view he or she assumes. If the author

chooses a first-person point of view and becomes one

of the characters, he or she has to assume a persona and

develop a character through that character’s thoughts,

actions, and speeches. This character is not necessarily sympathetic and is sometimes even a villain, as in

some of the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Readers

have to pick up this tone from the first few sentences. If

the author is writing a third-person narrative, the tone

will vary in accordance with how intrusive the narrator appears to be. Some narrators are almost invisible

while others are more intrusive, pausing to editorialize,

digress, or, in some cases, address the reader directly.

Language is the tool the author uses to reveal

attitude and point of view. A discussion of language

includes the writer’s syntax and diction. Are the sentences long or short? Is the length varied—is there an

occasional short sentence among longer ones? Does

the writer use parallelism and balanced sentence structure? Are the sentences predominantly simple, complex, compound, or compound-complex? How does

the writer use tense? Does he or she vary the mood of

the verb from indicative to interrogative to imperative?

Does the writer shift between active and passive voice?

If so, why? How do these choices influence the tone?

Occasionally, a set of questions may include a grammar question. For example, an item might require students to identify what part of speech a particular word is

being used as, what the antecedent of a pronoun is, or

what a modifier modifies. Being able to answer demonstrates that the student understands the sentence structure and the writer’s meaning in a difficult or sometimes

purposefully ambiguous sentence.

With diction or word choice, one must also consider

whether the words are learned and ornate or simple

and colloquial. Does the writer use slang or jargon?

Does he or she use sensual language? Does the writer

use figurative language or classical allusions? Is the

writer’s meaning clearer because an abstract idea is

associated with a concrete image? Does the reader

have instant recognition of a universal symbol? If the

writer does any of the above, what tone is achieved

through the various possibilities of language? Is the

writing formal or informal? Does the writer approve of

or disapprove of or ridicule his or her subject? Does he

or she use connotative rather than denotative words to

convey these emotions? Do you recognize a pattern of

images or words throughout the passage?

Some questions on vocabulary in context deal with a

single word. The word is not usually an unfamiliar word,

but it is often a word with multiple meanings, depending on the context or the date of the passage, as some

words have altered in meaning over the years.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

5

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

the passage is fiction, the purpose, unless it is a digression—and even digressions are purposeful in the hands

of good writers—will in some way serve the elements of

fiction. The passage will develop a character, describe

a setting, or advance the plot. If the passage is nonfiction, the writer’s purpose might be purely to inform;

it might be to persuade; it might be to entertain; or it

might be any combination of all three of these. Students

may also be questioned about the writer’s audience. Is

the passage intended for a specific group, or is it aimed

at a larger audience?

The easy part of the Critical Reading section is that

the answer to the question is always in the passage, and

for most of the questions, students do not need to bring

previous knowledge of the subject to the task. However,

for some questions, students are expected to have

some previous knowledge of the vocabulary, terms,

allusions, and stylistic techniques usually acquired in an

English class. Such knowledge could include, but is not

limited to, knowing vocabulary, recognizing an allusion,

and identifying literary and rhetorical devices.

In addition to recognizing the main idea of a passage, students will be required to demonstrate a more

specific understanding. Questions measuring this might

restate information from the passage and ask students

to recognize the most exact restatement. For such

questions, students will have to demonstrate their clear

understanding of a specific passage or sentence. A

deeper level of understanding may be examined by

asking students to make inferences on the basis of

the passage or to draw conclusions from evidence in

the passage. In some cases, students may be asked to

extend these conclusions by applying information in

the passage to other situations not mentioned in the

passage.

In reading for analysis, students are asked to recognize some aspects of the writer’s craft. One of these

aspects may be organization. How has the writer chosen

to organize his or her material? Is it a chronological narrative? Does it describe a place using spatial organization? Is it an argument with points clearly organized in

order of importance? Is it set up as a comparison and

contrast? Does it offer an analogy or a series of examples? If there is more than one paragraph in the excerpt,

what is the relationship between the paragraphs? What

transition does the writer make from one paragraph to

the next?

Other questions could be based on the writer’s

attitude toward the subject, the appropriate tone he or

she assumes, and the way language is used to achieve

that tone. Of course, the tone will vary according to the

passage. In informational nonfiction, the tone will be

detached and matter-of-fact, except when the writer is

particularly enthusiastic about the subject or has some

other kind of emotional involvement such as anger,

disappointment, sorrow, or nostalgia. He or she may

even assume an ironic tone that takes the form of exaggerating or understating a situation or describing it as

Sample Passage

To Prepare For Critical Reading

“We will each write a ghost story,” said Lord Byron, and his proposition was acceded to.

There were four of us. The noble author began a tale, a fragment of which he printed at the

end of his poem of Mazeppa. Shelley, more apt to embody ideas and sentiments in the

radiance of brilliant imagery and in the music of the most melodious verse that adorns our

(5)

language than to invent the machinery of a story, commenced one founded on the

experiences of his early life. Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed

lady who was so punished for peeping through a key-hole—what to see I forget:

something very shocking and wrong of course; but when she was reduced to a worse

condition than the renowned Tom of Coventry1, he did not know what to do with her and

(10) was obliged to dispatch her to the tomb of the Capulets, the only place for which she was

fitted. The illustrious poets also, annoyed by the platitude of prose, speedily relinquished

their uncongenial task.

I busied myself to think of a story—a story to rival those which had excited us to this task.

One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature and awaken thrilling

(15) horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the

beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be

unworthy of its name. I thought and pondered—vainly. I felt that blank incapability of

invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our

anxious invocations. “Have you thought of a story?” I was asked each morning, and each

(20) morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.

Mary Shelley

Introduction to Frankenstein (1831)

1. Tom of Coventry—Peeping Tom who was struck blind for looking as Lady Godiva passed by.

INSTRUCTIONS: On your answer sheet, mark the lettered space (a, b, c, d, or e) corresponding to the

answer that BEST completes or answers each of the following test items.

1. The author’s purpose in this passage is to

a. analyze the creative process

b. demonstrate her intellectual superiority

c. name-drop her famous acquaintances

d. denigrate the efforts of her companions

e. narrate the origins of her novel

2. A

ccording to the author, Shelley’s talents

were in

a. sentiment and invention

b. diction and sound patterns

c. thought and feeling

d. brightness and ornamentation

e. insight and analysis

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

6

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

In order to prepare for the critical reading portion of the test, it may be helpful for students to take a

look at a sample passage. Here is a passage used in an earlier test. The passage is an excerpt from Mary

Shelley’s 1831 Introduction to Frankenstein.

7. “

Noble” (line 2) can be BEST understood to

mean

a. principled

a. accurate

b. aristocratic

b. prejudiced

c. audacious

c. appreciative

d. arrogant

e. eminent

d. detached

e. exaggerated

a. amused

8. A

ll of the following constructions, likely to

be questioned by a strict grammarian or a

computer grammar check, are included in

the passage EXCEPT

b. sincere

a. a shift in voice

c. derisive

b. unconventional punctuation

d. ironic

c. sentence fragments

e. matter-of-fact

d. run-on sentences

5. T

he author’s approach to the task differs

from that of the others in that she begins by thinking of

e. a sentence ending with a preposition

a. her own early experiences

a. intellectual value

b. poetic terms and expressions

b. philosophical aspect

c. the desired effect on her readers

c. commonplace quality

d. outperforming her male companions

d. heightened emotion

e. praying for inspiration

e. demanding point of view

4. The author’s attitude toward Polidori is

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

3. T

he author’s descriptions of Shelley’s talents

might be considered all of the following

EXCEPT

9. In context “platitude” (line 11) can be BEST

understood to mean

6. At the end of the excerpt the author feels

10.“The tomb of the Capulets” (line 10) is an

allusion to

a. determined

a. Shakespeare

b. despondent

b. Edgar Allan Poe

c. confident

c. English history

d. relieved

d. Greek mythology

e. resigned

e. the legends of King Arthur

Answers and Explanations of Answers

1. (e) This type of question appears in most sets of critical reading questions. (a) might appear to be

a possible answer, but the passage does not come across as very analytical, nor does it seem like a

discussion of the creative process but rather is more a description of a game played by four writers to

while away the time. (b) and (c) seem unlikely answers. Mary Shelley’s account here sounds as if she is

conscious of inferiority in such illustrious company rather than superiority. She has no need to namedrop, as she married one of the illustrious poets and at that time was the guest of the other. She narrates

the problems she had in coming up with a story, but since the passage tells us that she is the author of

Frankenstein, we know that she did come up with a story. The answer is (e).

2. (b) This type of question asks readers to recognize a restatement of ideas found in the passage. The

sentence under examination is found in lines 3–6, and students are asked to recognize that “diction and

sound patterns” refers to “radiance of brilliant imagery” and “music of the most melodious verse.” (a)

would not be possible because even his adoring wife finds him not inventive. “Thought and feeling,”

(c), appear as “ideas and sentiments” (line 3), which according to the passage are merely the vehicles to

exhibit Shelley’s talents. Answer (d), incorporating “brightness,” might refer to “brilliant” in line 4, but

“ornamentation” is too artificial a word for the author to use in reference to her talented husband. (e) is

incorrect, as insight and analysis are not alluded to in the passage.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

7

3. (d) This question is related to Question 2 in that it discusses Shelley’s talents and the author’s opinion

of them. The writer is obviously not “detached” in her description of her very talented husband. She is

obviously “prejudiced” and “appreciative.” She may even exaggerate, but history has shown her to be

accurate in her opinion.

5. (c) This question deals with the second paragraph and how the author set about writing a story.

Choices (a), (b), (d), and (e) may seem appropriate beginnings for a writer, but they are not mentioned

in the passage. What she does focus on is the desired effect on her readers, (c), as outlined in detail in

lines 13–16.

6. (b) This question asks for an adjective to describe the author’s feeling at the end of the excerpt. The

expressions “blank incapability” (line 17) and “mortifying negative” (line 20) suggest that “despondent”

is the most appropriate answer.

7. (b) This question deals with vocabulary in context. The noble author is Lord Byron, a hereditary peer

of the realm, and the word in this context of describing him means “aristocratic.” “Principled,” (a), and

“eminent,” (e), are also possible synonyms for “noble” but not in this context. Byron in his private life

was eminently unprincipled (nicknamed the bad Lord Byron) and lived overseas to avoid public enmity.

(c) and (d) are not synonyms for “noble.”

8. (d) This is a type of question that appears occasionally in a set of questions on critical reading. Such

questions require the student to examine the sentence structure of professional writers and to be aware

that these writers sometimes take liberties in order to make a more effective statement.

They know the rules, and, therefore, they may break them! An additional difficulty is that the question

is framed as a negative, so students may find it a time-consuming question as they mentally check off

which constructions Shelley does employ so that by a process of elimination they may arrive at which

construction is not included. The first sentence contains both choices (a) and (e), a shift in voice and a

sentence ending in a preposition. Neither of these constructions is a grammatical error, but computer

programs point them out. The conventional advice is that both should be used sparingly, and they should

be used when avoiding them becomes more cumbersome than using them. The sentence beginning in

line 14 is a sentence fragment (c), but an effective one. Choice (b) corresponds to the sentence beginning

in line 6 and finishing in line 11, which contains a colon, semicolon, and a dash (somewhat unconventional)

without the author’s ever losing control. This sentence is not a run-on even though many students may

think it is! The answer to the question then is (d).

9. (c) Here is another vocabulary in context question. Knowing the poets involved and their tastes,

students will probably recognize that it is (c), the commonplace quality of prose, that turns the poets away

and not one of the loftier explanations provided in the other distracters.

10. (a) The allusion to “the tomb of the Capulets” in line 10 is an example of a situation where a student

is expected to have some outside knowledge, and this will be a very easy question for students. Romeo

and Juliet is fair game for American high school students. Notice that the other allusion is footnoted, as

this is a more obscure allusion for American high school students, although well known to every English

schoolboy and schoolgirl.

This set of ten questions is very typical—one on

purpose, a couple on restatement of supporting ideas,

some on tone and style, two on vocabulary in context,

and one on an allusion. Students should learn how to

use the process of elimination when the answer is not

immediately obvious. The organization of the questions is also typical of the usual arrangement of Critical

Reading questions. Questions on the content of the

passage, the main idea, and supporting ideas generally appear first and are in the order they are found in

the passage. They are followed by questions applying

to the whole passage, including general questions

about the writer’s tone and style. Students should be

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

8

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

4. (a) This is another question about the writer’s attitude. Some of the adjectives can be immediately

dismissed. She is not ironic—she means what she says. She is not an unkind writer, and she does not use

a derisive tone. However, there is too much humor in her tone for it to be sincere or matter-of-fact. The

correct answer is that she is amused.

setting, either outdoor or indoor, and the role it is likely

to play in a novel or short story.

Speeches generate some different kinds of questions because of the oratorical devices a speaker

might use—repetition, anaphora, or appeals to various

emotions. Questions could be asked about the use of

metaphors, the use of connotative words, and the use

of patterns of words or images.

The above suggestions should provide a useful background for critical reading. Questions are

likely to follow similar patterns, and knowing what to

expect boosts confidence when dealing with unfamiliar

material.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

9

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

able to work their way through the passage, finding the

answers as they go.

Additional questions on an autobiographical selection like this passage might ask what is revealed about

the biographer herself or which statements in the passage associate the author with Romanticism.

Since passages for critical reading come in a wide

variety of genres, students should keep in mind that

other types of questions could be asked on other types

of passages. For instance, passages from fiction can

generate questions about point of view, about characters and how these characters are presented, or about

SECTION

II:

Introduction:

Relationship to the Theme

I

n the closing chapter of You Can’t Go Home Again,

Thomas Wolfe’s narrator surveys the state of America

in the midst of the Great Depression, not only looking backward upon the vast wasteland created by

economic collapse at home, but also forward to the

growing threat of militaristic fascism abroad. While

Wolfe stands firm in his belief that America can find

itself once again, he feels compelled to warn his readers of his vision of “the enemy” who, assuming many

shapes, is the embodiment of the causes for a “lost”

America of the thirties. “I think I speak for most men

living,” Wolfe writes, “when I say that our America is

Here, is Now, and beckons on before us, and that this

glorious assurance is not only our living hope, but our

dream to be accomplished.”1 The warning which follows, however, offers a compelling portrait of America

in the Depression:

I think the enemy is here before us, too. But I

think we know the forms and faces of the enemy,

and in the knowledge that we know him, and

shall meet him, and eventually must conquer

him is also our living hope. I think the enemy is

here before us with a thousand faces, but I think

we know that all his faces wear one mask. I think

the enemy is single selfishness and compulsive

greed. I think the enemy is blind, but has the

brutal power of his blind grab. I do not think

the enemy was born yesterday, or that he grew

to manhood forty years ago, or that he suffered

sickness and collapse in 1929, or that we began

without the enemy, and that our vision faltered,

that we lost the way, and suddenly were in his

camp. I think the enemy is old as Time, and

evil as Hell, and that he has been here with us

from the beginning. I think he stole our earth

from us, destroyed our wealth, and ravaged and

despoiled our land. I think he took our people

and enslaved them, that he polluted the fountains of our life, took unto himself the rarest

treasures of our own possession, took our bread

and left us with a crust, and, not content, for the

nature of the enemy is insatiate—tried finally to

take from us the crust…. Look about you and see

what he has done.2

As Wolfe struggled to find artistic expression for

the political chaos of his time, John Steinbeck formed

characters who would live their lives in a battle with the

“enemy” who steals the land they’ve worked all of their

lives, forces them to join a vast sea of humanity migrating westward, and denies them work and sustenance

once they arrive. The shape of Steinbeck’s “enemy”

takes form in his defining fictional portrait of the Great

Depression, The Grapes of Wrath.

John Steinbeck’s Life (1902–68)

Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

NOTE TO STUDENTS: This year’s selected literature includes literary masterpieces by some of the greatest American writers in our nation’s

history. Some of these works contain profanity and deeply offensive racial slurs and address mature themes and topics. It is our hope that

Academic Decathletes will not only read and discuss these works with a scholarly appreciation for their richness and for the insights they provide into the topic of the Great Depression, but also will approach the subject matter with maturity and sensitivity.

Students should also be aware that all page references cited in the discussion of The Grapes of Wrath refer to the Penguin Classics edition of

the novel that is included in the bibliography at the end of the resource guide.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

10

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

John Steinbeck and

the Grapes of Wrath

— Closing lines from “Ulysses,”

Alfred Lord Tennyson

On December 20, 1968, John Steinbeck passed

quietly away, slipping into a coma after a long battle

with arteriosclerosis. At his funeral a few days later,

Henry Fonda, the actor who portrayed Tom Joad in

the film version of The Grapes of Wrath, read passages

from three of Steinbeck’s favorite poems, among them,

“Ulysses” by Alfred Lord Tennyson, whose closing lines

appear above. The lines suggest not an ending, but a

beginning, a fitting tribute to a writer whose work is

reborn with each new generation of readers.

Early Life and Education

John Steinbeck was born the third child of John and

Olive Steinbeck, on February 27, 1902. At the time of

his birth, Steinbeck’s parents lived in Salinas, California,

where his father served as the treasurer for Monterey

County. Steinbeck’s mother, who had been certified as

a teacher at the age of seventeen, gave up her profes-

sion after her marriage, but continued to serve as a

community leader. His mother provided a home filled

with books, an atmosphere that stimulated Steinbeck’s

imagination from a very early age. There is an additional important influence on Steinbeck, which came from

his mother’s side—his deep affection for his Hamilton

grandparents’ ranch about sixty miles south of Salinas.

The ranch provides the setting for Steinbeck’s The Red

Pony and figures prominently, along with the Hamilton

family, in East of Eden (1952). Among the early influences in his reading were works by Robert Louis Stevenson,

Alexandre Dumas, and Sir Walter Scott.

However, perhaps the most important influence

of all, one that would sustain Steinbeck throughout

his life, was his introduction to Thomas Malory’s Le

Morte d’Arthur. In one way or another, almost all of

Steinbeck’s fiction bears the mark of Malory. In fact,

Steinbeck planned and worked on a modern translation of Malory in the 1950s which was published posthumously in its unfinished form and entitled The Acts

of King Arthur and His Noble Knights (1976).

In high school, Steinbeck decided to become a

writer. While school itself didn’t seem to enchant him as

The John Steinbeck Map of America, Molly Maguire, Color Lithograph Map, Los Angeles:

Aaron Blake, 1986, Geograph and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

11

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.3

…the dark corridors of the school and the

desks in the ill-lighted room shining fiercely…the

grey light from the windows, and the teachers,

weekend over, facing us with more horror than

that with which we faced them.4

From the “horror” of the high school classroom,

Steinbeck entered the hallowed halls of Stanford

University, taking classes intermittently during a period

of six years, from 1919 to 1925 without ever completing

a degree. His record was only remarkable for the number of incompletes, withdrawals, and leaves of absence

he amassed, but he found a way to use his time at

Stanford to acquire the education he needed. After

several lengthy absences from the university, Steinbeck

realized that he did need a formal education of sorts

to accomplish his goals, so he reapplied for admission,

determined, however, to do it his own way.

One summer experience is worth mentioning in

some detail—Steinbeck enrolled in the Hopkins Marine

Station with his sister Mary for the summer quarter

in 1923. His instructor for general zoology had been

trained at Berkeley where the prevailing view of nature

was “organismal,” that is, a view that everything in

nature formed a whole in which the whole and its parts

were inextricably interrelated. The impact of this view

on Steinbeck’s later work and on his relationship with

Edward Ricketts, a marine biologist, is immeasurable.

From the time of his reentry at Stanford in January 1923

until he left in 1925, Steinbeck devised his own course

of studies, choosing classes in elementary Greek, writing, literature, and the classics, and avoiding his lowerdivision requirements. While at that time Stanford did

not offer a degree in creative writing, Steinbeck took

every course that was offered in the writing of fiction,

poetry, advanced composition, and journalism.

Arguably the most important influence on Steinbeck

at this time was his short fiction instructor, Edith

Mirrielees. Her insistence on a “lean, terse style”5 and

her demands for revision became increasingly important as Steinbeck learned his craft largely through

internalizing the lessons of his instructors as well as

by teaching himself through his writing. As Mirrielees

wrote in her own book on writing, which she was preparing for publication while Steinbeck was in her class:

There are a few helps towards general

improvement which it is feasible to offer, there

are many specific helps in the work of revision,

but help in the initial shaping of a story there is

none. That is the writer’s own affair.6

By the 1930s, Mirrielees’ lessons had taken root, for

Steinbeck was shedding the preference he displayed in

college publications for overblown figurative language

and began to find his voice in the lean, muscular style

of Tortilla Flat, Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of

Wrath.

Work Experience

During his frequent absences from Stanford,

Steinbeck worked to accumulate enough money to

return, finding employment as a store clerk, cotton

picker, and ranch hand, among other jobs. What he

learned on these jobs was as formative for the material of his writing as his Stanford classes were for the

development of his style. At some point during his

1920–January 1923 hiatus from Stanford, Steinbeck

stopped at a hobo camp and asked if anyone had a

good story. According to his biographer, Steinbeck

may have gotten the idea here for what would become

the ending of The Grapes of Wrath when one of the

hoboes, Frank Kilkenny, told him the story of how he

almost died and was saved by a Finn farmer’s wife who

gave him her breast to keep him from starving to death.

“I can use that,” Steinbeck told Kilkenny and paid him

two dollars.7

When he finally decided to leave Stanford without a

degree, Steinbeck continued to work, mostly as a laborer. He took a summer maintenance job at Lake Tahoe,

earning enough money to ship out on a freighter for

New York. His passage through the Panama Canal and

a stop in Panama City helped give him firsthand information that he would use later in his first novel Cup of

Gold. In New York, Steinbeck hoped he could make

a serious start on his writing career, but he needed to

work. He worked as a day laborer on the construction

of Madison Square Garden, which left him little time to

write; however, he was fortunate to get hired as a cub

reporter by the New York American. The job lasted only

a few months, though, as Steinbeck failed to meet his

deadlines, and he faced the reality that, without work,

he’d have to return to California.

The decision to return to the West was a fateful one,

for Steinbeck found work as a year-round caretaker on a

summer estate at Lake Tahoe. In the summer, his duties

were heavy, taking care of the family in residence, but in

the winter, he was alone, and finally had the chance to

establish a disciplined schedule for writing. Once he’d

escaped the initial inertia to begin writing, Steinbeck

set aside a time for writing each day, completing the

manuscript of Cup of Gold, his fictional biography of

the seventeenth-century pirate Henry Morgan, in late

January 1928. He also managed to publish his first

story, “The Gifts of Iban,” in The Smokers Companion

and began reworking a play that his friend Toby Street

had given him to complete. The unfinished play would

become the basis for Steinbeck’s third novel, To A God

Unknown.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

12

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

he was neither athletic nor extremely popular, he spent

a great deal of time at his desk in his room writing and

demonstrated a growing skill as associate editor of the

yearbook during his junior and senior years. His memories of high school suggest a sharp displeasure at the

necessity of returning to school on Monday mornings:

rate dust jacket designed by his artist friend Mahlon

Blaine. By this time, though, Steinbeck had put Captain

Morgan’s story behind him, feeling that the work had

little value, referring to it as the “Morgan atrocity.”8

He had also come into contact, at Carol’s urging, with

Ernest Hemingway’s story “The Killers.” Steinbeck felt

threatened by the sheer stark power of Hemingway’s

prose, telling Carol that Hemingway “was the finest

writer alive.”9 But, Steinbeck would avoid reading any

more of Hemingway’s work until much later.

Early Publication:

Cup of Gold (1929)

Cup of Gold: A Life of Sir Henry Morgan, Buccaneer,

with Occasional Reference to History is the expansion

of an earlier story, “The Lady in Infra-Red,” begun when

Steinbeck was still at Stanford. The novel is Steinbeck’s

only historical romance and bears the marks of so

many influences, especially the influence of Malory and

the quest for the Holy Grail, as is indicated in the title

itself. Of course, the “Cup of Gold” is also Panama, a

repository for Spanish gold during the early modern

period. Steinbeck mixes mythical characters with the

historical, like Merlin, from Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, as

a way of expanding the tale beyond fictional biography.

Morgan, as Steinbeck creates him, is a slave to his own

ambition, a man unfulfilled by his success and doomed

to “mediocrity.”10 The first edition of 1500 copies of the

novel appeared in August 1929, and by Christmas had

sold quite well. Even though Steinbeck found it objectionable, Mahlon Blaine’s rather gaudy dust jacket may

well have contributed to the book’s sales.

First Marriage,

Family Life, and Friendship

An undated photograph

of John Steinbeck.

As the stock market crashed in October 1929,

Steinbeck and Carol had begun to plan a life together.

They became engaged and moved south to Los

Angeles in anticipation of their wedding. On January

14, 1930, the Steinbecks celebrated their marriage in

Glendale and settled in Eagle Rock, in the hills above

Los Angeles. While there, Steinbeck worked on two

manuscripts, “Dissonant Symphony,” which he would

ultimately abandon and destroy, and “Murder at Full

Moon,” a potboiler mystery written in an effort to make

money, which remains unpublished today. Before these

two, though, Steinbeck had been hard at work on the

“Green Lady” manuscript given to him years before by

his friend, Toby Street. Steinbeck reworked this idea in

1929, giving it the new title “To an Unknown God” in

1930, and he continued to work on it for the next two

years.

1930 was a watershed year for Steinbeck not only

because of his marriage, but also for his fateful meeting

with Ed Ricketts, the man who influenced his work and

his thought more, perhaps, than anyone else. While

Ricketts was alive, Steinbeck produced almost all of

his major work; he collaborated with Ricketts on Sea of

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

13

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

In May of 1928, Steinbeck left his position as caretaker for the Brigham family estate and went to work

at the Tahoe Hatchery. That summer, Steinbeck met

the woman who would become his first wife, Carol

Henning. By the end of the summer, Steinbeck had

left the Hatchery to move to San Francisco to be near

Carol. But his work in a warehouse, coupled with the

time he devoted to his growing relationship with Carol,

left him little time to write. His solution to the problem

was to quit his job, move back to his parents’ summer

home in Pacific Grove, and accept a small monthly

subsidy from his father. The subsidy afforded him the

time and inspiration to work on the manuscript of “The

Green Lady,” which formed the basis of To A God

Unknown (1933), and to learn the process of writing and

destroying what he had written until he had sharpened

and clarified his prose.

In January 1929, Steinbeck learned that, through

the efforts of his friend Ted Miller, Cup of Gold had

been accepted by Robert M. McBride. The first edition

would appear in August of that year, with an elabo-

Life and Writing in the 1930s

Steinbeck continued to work at a feverish pace

through 1931, but he had not published a word since

Cup of Gold. By now, he had three completed manuscripts, all of which had been rejected, but by late

summer, he signed a contract with Mavis McIntosh and

Elizabeth Otis to represent him as his literary agents.

Their association would be lifelong, and their first success as his agents was the contract they secured with

Jonathan Cape for The Pastures of Heaven in February

1932.

The Pastures of Heaven (1932)

Cape went bankrupt that same year, but the manuscript was picked up by Brewer, Warren & Putnam and

published, finally, in October. The Pastures of Heaven

centers on a theme that is a Steinbeck mainstay—the

loss of the Garden of Eden. “Las Pasturas del Cielo,”

Steinbeck’s fictional valley, was based on the real Corral

de Tierra near Salinas. The twelve “chapters,” or stories,

in the novel are loosely connected through their geographical location and through the presence of a family, the Munroes, woven throughout, whose members

play a major or minor role in all of the chapters except

the first and last and who appear as the catalysts for the

misfortunes of the inhabitants of the valley.

The structure and themes of the collection reveal

the influence of Sherwood Anderson’s loosely connected stories in Winesburg, Ohio (1919) as well

as the influence of American Naturalist writers like

Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser. The underlying

tragedy traced through the stories is, as one critic has

pointed out, that “although this rich valley presents

the promise of a fulfilling life, the characters within it

are either so restricted or so driven by self-deception

and obsession that they do not make the most of their

abundant opportunities.11 Since its publisher went

bankrupt shortly after the novel’s release, the book was

not widely circulated and did not offer Steinbeck much

relief from financial pressure. The promise of payment,

though, did offer enough relief for the Steinbecks to

move back to the Los Angeles area in July 1932.

To A God Unknown (1933)

Photograph of Ed Ricketts, who

had a tremendous influence on the

life and work of John Steinbeck.

Photo courtesy of Pat Hathaway.

In early 1933, Steinbeck decided to withdraw his

manuscript “Dissonant Symphony” from circulation

and ultimately destroyed it. His work on “To an

Unknown God,” however, continued, its title changing

to To A God Unknown when he sent it to his agents.

The novel, so long in the making, finally appeared in

September 1933, published by Robert O. Ballou. The

development of the novel was heavily influenced by

Steinbeck’s friendship and many conversations with

Joseph Campbell, a leading authority on mythology.12

Campbell moved next door to Ricketts in 1932, just at

the time when Steinbeck was reworking the “Unknown

God” manuscript.

The final version of the novel incorporates mythological themes intertwined with a belief in pantheism,

mysticism, and the sacredness of nature. The protagonist, Joseph Wayne, literally weds himself to the land

he buys in a California valley, and at the end of the

novel allows himself to bleed to death in the mystical

belief that his self-sacrifice will restore the land from

drought. Here Steinbeck begins his preoccupation

with an important notion in his work—westward migration—as Joseph and his brothers leave Vermont to

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

14

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Cortez; and he repeatedly used Ricketts as a character

in his fiction.

The Steinbecks weren’t in Los Angeles a year before

finances forced their return to his parents’ summer

cottage in Pacific Grove in October, and once there,

Steinbeck became a frequent visitor at Ricketts’ laboratory in Cannery Row, Monterey. Ricketts was a student

of marine life without a formal degree who collected

and provided specimens to biological supply houses.

With Ricketts, Steinbeck forged not only a friendship,

but also a philosophical world view heavily influenced

by his study of and discussions about science.

Steinbeck’s childhood home

in Salinas, CA. In March 1933,

Steinbeck and his wife Carol moved

back to this Salinas home to care

for Steinbeck’s aging parents.

forcing its way in on Steinbeck—the increase in labor

strikes all over California. Steinbeck collected material

from scenes of unrest in his own neighborhood, meeting fugitive labor organizers, striking farm workers,

and members of the Young Communist League. These

events gave Steinbeck his most powerful themes and

led directly to three of his greatest works: In Dubious

Battle, Of Mice and Men, and The Grapes of Wrath.

Tortilla Flat (1935)

Tortilla Flat, originally meant to be a collection of

stories, had by early 1934 become instead an episodic

novel. The publication of this novel marked the beginning of Steinbeck’s fame. Its characters comprise a

subculture of the Mexican-American community in

Monterey called “paisanos,” or countrymen, because,

in addition to Mexican and Indian blood, many of them

also had either Italian or Portuguese ancestry. The

novel produces, with comic overtones, a retelling of

the tale of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round

Table played by the poverty-stricken inhabitants of

Tortilla Flat. Steinbeck needed to write something light

to relieve the suffering he endured as he watched the

decline of both parents, and he was fortunate to have

his work introduced to Pascal Covici, the publisher who

would be his friend and editor for the rest of his life.

Covici agreed to publish Tortilla Flat in February 1935.

With its emphasis on the lower class and its use of the

vernacular, Tortilla Flat may be seen as an introduction to Steinbeck’s great proletarian novels that would

follow.

Despite his father’s continued failing health,

Steinbeck now had more time to begin research on

what would become his great theme—the plight of the

California farm worker. Migrants from the Dust Bowl

had begun arriving in the Salinas area in early 1934,

establishing a “Hooverville” camp just outside the

city. Steinbeck was aware of this movement, and as he

started collecting information about the clash between

the farm workers and the growers, he met two strike

organizers who were hiding from arrest and offered to

pay them for their stories.14

As a response to falling wages, agricultural workers, who had been spurned by traditional labor unions,

engaged in a number of strikes between 1930 and

1932. Without organization, though, the strikes could

not help but fail. With the help of the Communist Party

USA, workers formed the Cannery and Agricultural

Workers’ Industrial Union (CAWIU) from earlier parent

organizations in 1931, which helped secure modest

gains in wages. Steinbeck met a number of people associated with the movement, including Lincoln Steffens,

a journalist and “muckraker” who in the early decades

of the century had sought to expose corruption in business and government. Steffens and his wife Ella Winter

hosted a wide circle of activists at their home in Carmel,

among them, George West, with the San Francisco

News, who later asked Steinbeck to write a series of

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

15

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

farm in California. The novel offers an early example

of Steinbeck’s theory of “non-teleological” thinking,

a theory he and Ricketts debated and which, for

Steinbeck at this early stage of his development of the

concept, incorporated the belief in a universe which

operates almost like a machine, independently of God

or man, where things just happen without cause or

explanation.13

In March 1933, Steinbeck’s mother suffered a devastating stroke, so Steinbeck and his wife moved back

to the family home in Salinas to help with her care. It

was hard for Steinbeck to maintain continuity in his writing during this period, but perhaps the circumstances

which forced him to face his mother’s mortality also

inspired him to begin work on narratives drawn from his

own childhood, a collection of stories which would later

appear in The Red Pony (1938). Faced not only with

his mother’s rapidly declining health, but also with his

father’s increasing frailty, Steinbeck devoted himself to

short fiction for more than a year. The stories produced

during this period included the four stories collected

as The Red Pony (“The Gift,” “The Great Mountains,”

“The Promise,” and “The Leader of the People”), the

remaining stories collected later in The Long Valley,

and stories that, reworked, would become Tortilla Flat.

On February 19, 1934, Steinbeck’s mother died following a second stroke. Within a week, while caring for

his father, Steinbeck finished one of his most widely

anthologized stories, “The Chrysanthemums.” Within

another two weeks, Steinbeck had finished the manuscript “Tortilla Flat,” and his story “The Murder,” published in the North American Review, won the O. Henry

Prize in April. In addition to health issues with his parents in 1933–34, another pressure from the outside was

In Dubious Battle (1936)

In Dubious Battle is considered the first of Steinbeck’s

“Labor Trilogy,” his fictional account of the atrocities he

witnessed against Dust Bowl migrants and itinerant

farm workers. The story has a minimum of narrative and

consists in large part of vernacular dialogue, frequently

profane and obscene. The novel is also important for

the appearance of the character “Doc,” loosely patterned on Ed Ricketts. Doc serves as a one-man Greek

chorus, commenting on the actions in the narrative

Pickets on the highway calling

workers from the fields during

the 1933 cotton strike.

International News Photos, Inc.

Photo courtesy of Bancroft Library.

and extrapolating from them philosophical lessons,

especially his theory of “group-man” on the mechanistic behavior of human beings in groups. Furthermore,

Steinbeck cast an argument he had introduced in a

1933 essay, “Argument of Phalanx,” in fictional form

here in an effort to observe the behavior of humans

individually and within a group.18

Steinbeck refuses to take a side in the novel, choosing instead to present two forces in combat whose

outcome can only be “dubious.” Another point to be

made here is that the actual strike on which the novel

is, in part, based included a vast majority of Mexican

and Filipino farm workers while Steinbeck’s strikers are

largely white. Steinbeck, from personal experience,

could not have failed to be aware of the ethnic diversity

of the workers, but his greatest sympathies seemed

reserved for poor white farm workers. Perhaps, too,

he chose to focus on a more homogeneous group

that could demonstrate the efficacy of his theory. By

February of 1935, Steinbeck had finished the manuscript for the novel, and by August, he had a contract

with Covici-Friede. By the time Steinbeck signed the

contract for In Dubious Battle, Tortilla Flat had become

a bestseller.

During this period of burgeoning success for

Steinbeck, there was also sadness. His father finally

succumbed to illness and died in May 1935. Finally

free of tending to sick and dying parents, Steinbeck

and his wife Carol traveled to Mexico and New York

in the fall. The year 1936 opened with promises of

further success for Steinbeck. He signed a contract

with Paramount Pictures for the movie rights to Tortilla

Flat. In Dubious Battle appeared and sold well, and

in April Steinbeck began the manuscript provisionally

entitled “Something That Happened,” the first version

of Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck worked simultaneously

on this manuscript while writing a series of articles on

migrant workers for the San Francisco News, published

as “The Harvest Gypsies,” from October 5–12. These

articles were based on Steinbeck’s travels in an old

bakery truck, accompanied by Tom Collins, a federal

government labor camp manager, to migrant and government camps in the San Joaquin Valley. Within a

month, Steinbeck had begun work on an early draft,

which would later be destroyed, entitled “L’Affaire

Lettuceberg,” the first attempt at what would later

become The Grapes of Wrath.

By March of 1936, Steinbeck had finished the first

draft of Of Mice and Men, designing it as an experiment—it was a novel that could also double as a stage

play. Two months later, though, his setter puppy had

destroyed about half of the manuscript. Steinbeck

wrote to his agent, “I was pretty mad but the poor

little fellow may have been acting critically.”19 After

a trip to Baja California with Ricketts to collect octopuses, Steinbeck went back to work on the manuscript,

which progressed simultaneously with the construction

of a new house in Los Gatos in the summer of 1936,

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

16

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

articles on Dust Bowl migrants. Those articles served

as the research for and the backbone of The Grapes of

Wrath. First, though, Steinbeck was impelled to write a

novel about a strike.

With the help of leftist sympathizers who wanted the

story to get out, Steinbeck met Cicil McKiddy (an alias),

a Dust Bowl migrant and labor organizer who had been

sent into hiding in Seaside to avoid possible arrest.

McKiddy participated in the “largest single agricultural

strike in American history,”15 the cotton strike in the

San Joaquin Valley in October 1933. The great cotton

strike possessed the “epic sweep worthy of the Great

Depression,”16 and McKiddy had been in a position to

know much of what occurred during the strike. He was

especially knowledgeable about CAWIU organizer and

strike leader Pat Chambers. Steinbeck spent hours with

McKiddy gathering information that would become

the core of In Dubious Battle. The novel, however, is

not meant to be a documentary of the cotton strike;

Steinbeck himself refused to acknowledge a particular

geographical location or a specific strike as the scene

of his novel.17

designed and supervised by Carol as a response to

Steinbeck’s increasing need for privacy to write.

In Depth: Of Mice and Men (1937)

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Steinbeck finished the manuscript in mid-August of

1936, titling it Of Mice and Men, a reference to a line

from Robert Burns’ “To a Mouse,” which reads: “the

best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley”

(often paraphrased as: “The best laid schemes of mice

and men go oft awry”). Because of Steinbeck’s intent

to dramatize the novella, much of its discourse is dialogue, for what Steinbeck may have had in mind was

an audience of working poor who, though they might

not read books, would attend a play.20 The main characters are hoboes, or “bindlestiffs,” George Milton and

Lennie Small, whose dream to “live offa the fatta the

lan’” is doomed from the beginning.

Poor mother and children during the Great Depression. Elm Grove, California. As he

toured migrant camps, Steinbeck became outraged by the deplorable conditions.

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

2010–2011

§

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

17

Their Blood is Strong (1938)

In March 1938, Steinbeck was approached by Helen

Hosmer on behalf of the Simon J. Lubin Society, who

asked for permission to reprint “The Harvest Gypsies,”

the series of articles on the deplorable conditions in

migrant worker camps that he had written for the San

Francisco News. Her intent was to use the money made

on the pamphlet to aid the migrants. Steinbeck agreed

and added an essay to the original seven. Illustrations

included photographs by Dorothea Lange on the front

and back covers of the pamphlet, which Hosmer retitled Their Blood is Strong.

As Steinbeck grew increasingly impassioned about

the plight of migrant farm workers, his success continued to mount. Steinbeck’s play version of the novel

Of Mice and Men appeared on Broadway and subsequently won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award

for the best American play of the season. Additionally,

he had published a number of short stories in various

magazines, had consulted with producers and directors in Hollywood about a film version of In Dubious

Battle, and had received two gold medals from the

Commonwealth Club of California for Tortilla Flat and

In Dubious Battle. Steinbeck’s editor and publisher,

Pascal Covici, had declared bankruptcy, but went to

Viking Press as senior editor, taking Steinbeck with

him.

The Long Valley (1938)

In September 1938, Viking published a collection of

Steinbeck’s stories titled The Long Valley. The collection included a number of stories previously published

in magazines, including “The Chrysanthemums,” considered the finest example of Steinbeck’s short fiction,

and the four stories which comprise The Red Pony. The

stories are set in California’s Central Valley, and many

introduce themes which appear in Steinbeck’s later

novels. In August 1938, the Steinbecks, still in search

of privacy which they had not acquired in their current

Los Gatos home, purchased the fifty-acre Biddle Ranch

in Los Gatos and worked on constructing their second

new house. By the end of the year, working day and

night, Steinbeck finished The Grapes of Wrath, with

the new title suggested by Carol, who also typed the

manuscript.

The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Film (1940)

Despite the pleading of Elizabeth Otis, his agent,

in January 1939, Steinbeck refused to change much of

the language in The Grapes of Wrath manuscript, nor

would he agree to change the controversial ending. By

April 1939, the novel was out and became an immediate bestseller. Steinbeck was elected to the National

Institute of Arts and Letters. While his writing was being

met with great success, Steinbeck’s personal life was

crumbling. His marriage had been in trouble for some

time, and Steinbeck spent much of the early part of

1939 away from home. In September, the Steinbecks

tried to salvage their marriage, taking a trip to the

Pacific Northwest and then traveling on to Chicago; but

in June, while working in Los Angeles, Steinbeck had

already met the woman who would be his next wife,

Gwyndolyn Conger. By December, Steinbeck was back

in Los Angeles for film screenings of both The Grapes

of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. Eugene Solow’s

screenplay for Of Mice and Men preserved most of

Steinbeck’s dialogue, only softening the language and

altering the ending to comply with Hollywood’s Hays

decency code. The film was nominated for best picture

but lost to Gone With the Wind. After previewing the

film version of The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck wrote

his agent: “it looks and feels like a documentary film

and certainly it has a hard, truthful ring.”22

Unauthorized Duplication is Prohibited Outside the Terms of Your License Agreement

18

LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE RESOURCE GUIDE

§

2010–2011

MONTVILLE HS - OAKDALE, CT

Both men work as itinerant ranch hands, saving for

their dream of owning their own ranch, an unattainable quest. Lennie, whose mental incapacity is in sharp

contrast to his huge strength, operates instinctively,

and these limitations set the stage for his demise. First,

Lennie pets a puppy to death and then kills the wife

of the ranch owner’s son, Curley, when he tries to

stroke her hair and she struggles against him. George,

Lennie’s self-appointed caretaker, realizes that he can’t

control or help Lennie and shoots him in the back of the

head as he soothes him with the tale of the ranch they’ll

own someday. Steinbeck’s original title for the novel,

“Something That Happened,” suggests Steinbeck’s

determination to present life as non-teleological—the

story of George and Lennie is simply something that

happened without an exploration of grand, overarching causes. When the novel appeared in February 1937,

it hit the bestseller list almost immediately, and the

Steinbecks decided to leave for Europe.

From May through August, the Steinbecks traveled

to Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and the Soviet Union.

Back in California in the fall, Steinbeck saw several of his

stories published in Harper’s Magazine and Esquire. At

this point, Steinbeck took another tour of the migrant

camps in the Central Valley to gather information.

There, he witnessed the appalling poverty and disease

of a portion of the more than 70,000 migrants from the

Dust Bowl who had gathered in the San Joaquin Valley

during the summer of 1937. By now, the large growers

had beaten union organizers and resumed control of

the state’s agriculture. In February and March 1938,

Steinbeck visited the Visalia area in the aftermath of

devastating floods; now he could use his fame to get

the conditions of the migrants reported in newspapers,

which had notoriously ignored them. When he returned

again in March, he was accompanied by Life photographer Horace Bristol. “I want to put a tag of shame,”

Steinbeck wrote his agent, “on the greedy bastards

who are responsible for this but I can do it best through

the newspapers.”21

Sea of Cortez (1941)

As a new decade dawned, the world was at war.

Hitler had invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, an

action which precipitated declarations of war against

Germany by Great Britain and France, and Steinbeck

would become increasingly involved in the war effort.

In early 1940, his fame as a writer continued to climb.

First, the world premiere of The Grapes of Wrath

opened in New York City in January 1940, followed by

awards for the novel from the American Booksellers

and Social Work Today. The most important award to

date, though, came on May 6—the prestigious Pulitzer

Prize in fiction; in the same year Carl Sandburg won

in history for his biography of Abraham Lincoln and

William Saroyan won for drama. When Steinbeck was

asked to comment on Saroyan’s refusal to accept

the prize for drama, he chose not to, writing instead:

“While in the past I have sometimes been dubious

about Pulitzer choices I am pleased and flattered to

be chosen in a year when Sandburg and Saroyan were

chosen. It is good company.”23 In the midst of such

acclaim, Steinbeck continued to work as hard as ever.

Steinbeck spent March and April with Ricketts, Carol,

and four crew members on a specimen-collecting trip

to the Gulf of California; the research from the trip

would result in Steinbeck and Ricketts’ collaborative

publication of Sea of Cortez.

In early January 1941, Steinbeck had begun the

manuscript for Sea of Cortez. Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely

Journal of Travel and Research consists of two parts: a

narrative portion, written largely by Steinbeck, which

he would later publish separately as The Log from the

Sea of Cortez (1951), and a lengthy annotated catalogue of the marine life examined, which was largely

Ricketts’ contribution. The journal or “log” details the

daily activities in scientific collecting, interactions with

the local population, and philosophical musings about

the broader meanings of the authors’ experiences. The

work, published just two days before the Japanese

attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, went