Access to lAnd And productive resources

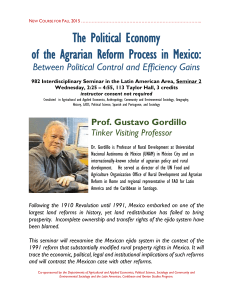

advertisement