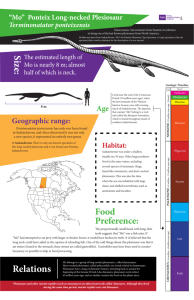

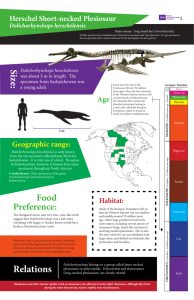

Plesiosaurs from Svalbard - DUO

advertisement