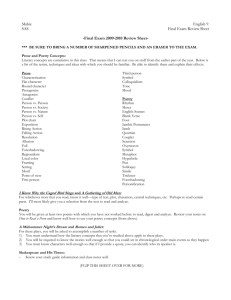

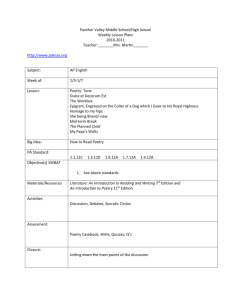

poetry in america - Poetry Foundation

advertisement