Comparative Hate Crime Research Report

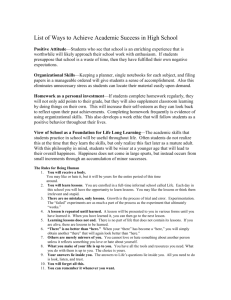

advertisement