Intelligence and the war in Bosnia 1992-1995

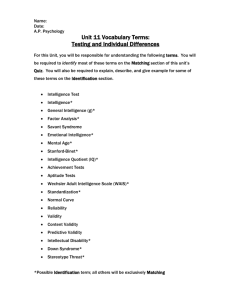

advertisement