The Stice model of overeating - Developmental Psychopathology

Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 www.elsevier.com/locate/appet

Research Report

The Stice model of overeating: Tests in clinical and non-clinical samples

Tatjana Van Strien

a,

*, Rutger C.M.E. Engels

b

, Jan Van Leeuwe

c

, Harrie¨tte M. Snoek

b a

Department of Clinical Psychology and the Institute for Gender Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen. P.O. Box 9104, 6500 HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands b

Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University Nijmegen. P.O. Box 9104, 6500 HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands c

Statistical Consultancy Group, Radboud University Nijmegen. P.O. Box 9104, 6500 HE Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Received 9 February 2005; revised 1 July 2005; accepted 23 August 2005

Abstract

The present study tested the dual pathway model of Stice [

. A review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa and an exploration of the mechanisms of action.

Clinical Psychology Review , 14 , 633–661 and

Stice, E. (2001) . A prospective test of the

dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: mediating effects of dieting and negative affect.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 110 , 124–135.] in a non-clinical sample of female adolescents and a clinical sample of female eating disorder patients. The model assumes that negative affect and restrained eating mediates the link between body dissatisfaction and overeating. We also tested an extended version of the model postulating that negative affect and overeating are not directly related, but indirectly through lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating. Structural equation modelling was used to test our models. First, in the two samples, body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness were associated with overeating/binge eating. In both clinical and adolescent sample, we found support for the negative affect pathway and not for the restraint pathway. Lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating appear to (partly) explain the association between negative affect and overeating.

Emotional eating was much more strongly associated with overeating in the clinical than in the adolescent sample. In sum, we found substantial evidence for the negative affect pathway in the dual pathway model. The link between body dissatisfaction and overeating in this respect might be explained by the fact that negative affect, due to body dissatisfaction, is related to a lack of awareness of personal feelings and to eating when dealing with negative emotions, which on its turn is associated with overeating.

q

2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Binge eating; Overeating; Restrained eating; Dual pathway model; Negative affect; Interoceptive awareness.

Body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness, as a result of internalisation of thin body images idealised in the mass media, are considered risk factors for bulimic pathology in female adolescents. In a social cultural model of bulimic behaviour the dual pathway model

proposed that body dissatisfaction and bulimic behaviour are linked through two pathways. Firstly, the pathway of dietary restraint and secondly, the pathway of negative affect. In the pathway of dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction results in dietary restraint, i.e.

eating less than desired, because of the majority view that this is an effective weight control technique. Dietary restraint in turn is hypothesised to be an important risk factor for eating pathology, as for metabolic and psychological reasons it sows the seeds of its

, p. 90) and produces overeating

(

). Secondly, in the pathway of negative affect, body dissatisfaction may result in negative

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: vanstrien@psych.ru.nl (T.V. Strien).

0195-6663/$ - see front matter q

2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.appet.2005.08.004

emotions, such as depression and this, in turn, to bulimic behaviour, because overeating may serve to distract people from

feelings of aversion ( Heatherton and Baumeister, 1991 ).

There is evidence that body dissatisfaction is associated with dietary restraint (e.g.

,

Van Strien, 1989 ), but the hypothesised link between dietary

restraint and binge eating/overeating has met inconsistent support. This hypothesised link is based on the early laboratory work by

Herman and Polivy (1980) , in which subjects high on

restraint overate when their self-control had been deliberately undermined. But the link between dietary restraint and overeating has not been replicated in experimental studies with other measures for restraint than the original Restraint

Scale,

1 possibly because a different sort of dieter will be

1

The association between restraint and overeating has not been found with the restraint scales of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ;

Strien, Frijters, Bergers, and Defares, 1986 ), nor with the Three Factor Eating

Questionnaire (TFEQ;

Stunkard and Messick, 1985 )(studies by

Oosterlaan, Merckelbach, and Van Der Hout, 1988 ;

;

Wardle and Beales, 1987 ; Van Strien, Cleven, and Schippers, 2000

;

Ouwens, Van Strien, and Van Der Staak, 2003a

,b).

206 T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 selected by these scales (

Heatherton, Herman, Polivy, King, and McGree, 1988 ;

;

2

Further, although self-reported dieting was associated with subsequent increase in bulimic pathology in various longitudinal studies

(e.g.

Stice, 2001 ; Stice and Agras, 1998 ), experiments on actual

caloric deprivation (the prescription of a low-calorie diet) did not consistently support the link between dieting and binge

eating ( Howard and Porzelius, 1999 ). Effective dietary

restriction was even found to reduce bulimic pathology (e.g.

Presnell and Stice, 2003 ), indicating the existence of

potentially successful dieters (see also

;

1989 ; Westenhoefer, 1991 ; Van Strien, 1997

).

Apart from the possibility that many restrained eaters do not develop binge eating, dieting may not be a necessary precondition for overeating, as a significant number of subjects with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder retrospectively reported that in their case binge eating preceded attempts to diet or purge (

Bulik, Sullivan, Carter, and Joyce, 1997

;

Mitchell, Fenna, Crosby, Miller, and Hoberman, 1997

). This opens the possibility that bulimia is preceded by a different pathway than restraint. In the second pathway of the dual pathway model, the relationship between body dissatisfaction and bulimic pathology is mediated by negative affect (

1994 ; Stice Nemoroff and Shaw, 1996

).

There is indeed support that body dissatisfaction is

associated with negative affect ( Groesz, Levine, and Murnen,

Stice and Shaw, 1994 ) and the supposition that negative

affect may result in overeating is consistent with the widespread belief that distress may lead to overeating. In this general effect model

( Greeno and Wing, 1994 ) distress, through

a general physiological stress response, may increase eating in all exposed organisms. Unfortunately the problem with this model is that it has been tested primarily with animals and physical stressors, but that current evidence on humans and psychological stressors more strongly point to an individual difference model (

). In an individual

difference model ( Schachter, Goldman, and Gordon, 1968 ) the

normal response to distress is loss of appetite, while stressinduced eating is the abnormal response, for the physiological effects include the inhibition of gastric contractions and the elevation of blood sugar levels, which both ought to suppress hunger. Increased eating in response to psychological distress, such as depression or anxiety, so called emotional eating , may occur in people who, as a result of learning experiences early in life, confuse emotional distress with hunger, due to lack of

interoceptive awareness ( Bruch, 1973 ;

Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, and Early-Zald, 1995

). In this line of thought there is no direct line between negative affect and overeating, but it runs through lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating instead.

2

Also in studies with the Restraint Scale as measure for restraint, it was not

consistently supported as on close inspection ( Ouwens, Van Strien, and Van

). In addition, actual counterregulation was only found in three preload taste test studies with RS-restrained eaters (

Herman, Polivy, and Esses, 1987 ;

Polivy, Heatherton, and Herman, 1988 ).

depression anxiety

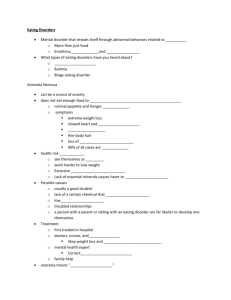

Fig. 1. Test of original dual pathway model: student sample.

The present study’s aim is to test both the dual pathway model by Stice and a second extended model in which negative affect and overeating are indirectly related through the intervening concepts lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating (

Fig. 1 ). Both models were tested in two

samples: (1) in female adolescents, for binge eating typically emerges in middle adolescence and this sample may therefore permit assessment of etiological factors for overeating; (2) in female eating disorder patients, for binge eating has a high prevalence in this sample and this sample may therefore permit assessment of maintaining factors for overeating (see also

Stice, 2001 ). Although longitudinal data may permit firmer

causal inferences this model was initially tested with crosssectional data, for an inaccurate model can still be rejected with contemporaneous data (see also

Stice, Nemoroff, and Shaw, 1996 ).

Method

Female adolescents

.79

low body esteem

.79

body dissatisfaction

.90

drive for thinness

.33

restrained eating

A sample of 436 female adolescents had been obtained from six different schools in the eastern part of the Netherlands in various levels of education varying from lower vocational to pre-university education. They had a mean age of 15.6 years

(SD

Z

1.5) and a mean BMI (body mass index; weight/height

!

height) of 20.06 (SD

Z

2.6). The questionnaire with the measures to study was administered under the supervision of both the teacher and the researcher after the students’ parents had given their permission.

Female eating disorder patients

.17

negative affect

1.00

.78

ns

–.08

.28

overeating

Patients suffering from an eating disorder were enrolled from two Dutch clinics that specialized in the treatment of eating disorders (Amsterdam and Warnsveld). As diagnosed by a trained clinical psychologist at intake, a total of 26 patients met the criteria for restrictive anorexia nervosa; 32 patients met the criteria for bulimic anorexia nervosa; 88 patients met the criteria for bulimia nervosa; 13 patients met the criteria for binge eating disorder and the remaining patients were diagnosed with eating disorders non-specified, as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-IV,

American Psychiatric Association, 1994 ). In the

present study, all eating disorder patients had been included and not only those with overeating/binge eating problems, to avoid restriction of range. Additionally, the majority of patients in these two Dutch clinics did not meet a specific eating disorder diagnosis anyway and those patients who did showed considerable heterogeneity of symptoms within each diag-

nostic group ( Van Strien and Ouwens, 2003

; see also

). The clinical psychologists used the EDI screening as an aid to assess eating disorders. At intake all patients completed a questionnaire including some of the instruments described below. Their mean age was 25.4 years (SD

Z

6.2) and their mean BMI was 19.08 (SD

Z

4.56).

Measurements

In addition to the general questions, about age, weight, height, menstruation, dieting, overeating and vomiting (see

Van Strien, 1997 ) the assessments in the present study

comprised the following questionnaires: the EDI-SC, the Dutch version of the EDI-2, the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire, and the revised version of the Hopkins Symptom

Checklist, the SCL-90-R.

The Eating Disorder Inventory Symptom Checklist (EDI-SC)

(

) is a self-report measure for frequency of specific eating symptoms, such as binge eating and self-induced vomiting.

For the purpose of this paper, we used two items assessing lifetime binge eating and frequency of binge eating in the past 3 months (see also

Byrne and McLean, 2002 ). The answers on both

questions were combined, resulting in a categorical scale with the following answer categories: (0) I never had an eating binge; (1)

In the past 3 months I never had an eating binge; (2) In the past

3 months I had eating binges on a monthly basis; (3) In the past 3 months I had eating binges on a weekly basis; (4) In the past

3 months I had eating binges on a daily basis.

Binge eating was defined as follows: Please remember when answering the following questions that an eating binge only refers to eating an amount of food that others of your age and sex regard as unusually large. It does not include times when you may have eaten the normal quantity of food, which you would have preferred not to eat.

It should be noted that this measure of binge eating could be best perceived as self-perceived overeating (in correspondence with the actual overeating shown by some subjects in

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 207 preload-taste test studies in the psychological laboratory). It does not assess binge eating in its true sense, as it does not assess whether the person experienced a sense of loss of control, an essential aspect of DSM-IV binge eating. It also does not assess vomiting or use of laxatives (essential features of DSM-

IV bulimia nervosa). Nevertheless, the combined scale on binge eating frequency showed good concurrent validity for other measures for binge eating/bulimia nervosa, for we found high correlations with the EDI-II bulimia scale (0.65 (adolescent sample) and 0.81 (clinical sample)) and a correlation of 0.78

with a seven-category item assessing the frequency of binge eating in the past 28 days in the clinical sample (the adolescent sample did not fill out this item). The measure of binge eating is henceforth indicated as overeating/binge eating (BE).

The Revised Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI-II) ( Garner,

) is a self-report measure of attitudes and behaviours concerning eating, weight and shape, and psychological traits clinically relevant to eating disorders. Verification of the Dutch translation—for which the copyright owner, Psychological

Assessment Resources, had granted permission—by a professional translator had not yielded any meaningful differences

with the original ( Schoemaker et al., 1994 ). In the present

study, the subscales drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and lack of interoceptive awareness was used. The first two scales refer to issues directly related to weight control such as preoccupation with weight and unhappiness with thighs and hips. Interoceptive awareness reflects difficulties in recognizing and accurately identifying emotions or unusual sensations of hunger or satiety. Response categories ranged from 1 ‘never’ to 6 ‘always’. In contrast with the EDI manual (

in which a transformation of responses into a four-point scale is advocated, the present study utilized untransformed responses, as scale transformation was found to damage the validity of the EDI among a non-clinical population (

Strien, and Van der Staak, 1994 ) and untransformed responses

were found to also work well in a clinical population of female patients suffering from eating disorders (

Ouwens, 2003 ). Scales were constructed by calculating the

means for all scales.

Alphas were: drive for thinness 0.79 (adolescent sample) and 0.81 (clinical sample), body dissatisfaction 0.93 (adolescent sample) and 0.90 (clinical sample), and lack of interoceptive awareness 0.68 (adolescent sample) and 0.74

(clinical sample).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for student sample ( N Z 436) and clinical sample ( N Z 332)

Body dissatisfaction

Drive for thinness

Depression

Anxiety

Lack of interoceptive awareness

Restrained eating

Emotional eating

Overeating/binge eating

Student sample

Mean SD

32.5

17.9

1.60

1.56

24.3

2.26

2.12

0.56

12.8

7.0

0.55

0.59

5.9

0.88

0.74

1.00

Min.

12

1

1

0

0

0

9

7

Max.

54

5

5

4

54

40

5

5

Clinical sample

Mean SD

43.3

31.9

3.15

2.68

39.7

3.93

3.39

2.30

9.8

6.7

0.88

0.94

7.6

0.81

1.11

1.62

Min.

14

1

1

0

14

9

0

0

Max.

60

5

5

4

54

42

5

5

T -test

T

13.331

27.842

28.213

19.152

30.405

27.296

18.018

17.201

P

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

208

The DEBQ scales assessing emotional, external, and restrained eating behaviour. We employed the subscales emotional and restrained eating in the current study. Each of the scales showed to have good internal consistency and factorial validity

(e.g.

Strategy for analyses

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213

(Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire;

Strien, Frijters, Bergers, and Defares, 1986

for food consumption,

3

;

and high convergent and discriminative validity (

Van Strien, 2002 ). Furthermore, scores on the

restrained eating scales were strongly correlated with the

Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-R;

Messick, 1985 ). The average correlation in several clinical and

non-clinical samples between the DEBQ-R and the TFEQ-R

). Response categories ranged from

1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘very often’. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscale emotional eating were 0.93 (adolescent sample) and 0.96

(clinical sample), and of restrained eating 0.93 (adolescent sample) and 0.90 (clinical sample).

Hopkins Symptom Checklist, the SCL-90-R

1977 ) is a self-report measure for indications of psychopathol-

ogy. The subscales anxiety and depression were used for assessments of negative affect. Response categories for each of the complaints ranged from 1 ‘not at all applicable’ to 5 ‘very much applicable’. Internal consistencies were 0.88 (adolescent sample) and 0.91 (clinical sample) for depression, and 0.88

(adolescent sample) and 0.89 (clinical sample) for anxiety.

negative affect and overeating/binge eating. As overeating/ binge eating was measured on a five-point scale, models were estimated in Mplus by considering this variable ordered categorically. Robust estimates were obtained by using the weighted least squares estimation method. Goodness-of-fit was verified by the c

2 statistics as well as by the fit-indices:

Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

According to

and

, the following fit index cut-off value guide for good models are: TLI O 0.95, CFI O 0.95 and RMSEA !

0.06.

Results

Preliminary analyses

First of all, the correlation structures of the data obtained in the sample of female adolescents and the clinical sample were compared to analyse whether the non-clinical and clinical data should be analysed separately or in combination. A comparison between data of the clinical and non-clinical sample tested the hypothesis that both covariance matrices were calculated from random samples of one population. By testing this hypothesis with regard to the eight variables involved Body Dissatisfaction (BD), Drive for Thinness (DT), Lack of Interoceptive

Awareness (IA), Depression (DE), Anxiety (ANG), Restrained

Eating (RE), Emotional Eating (EE), and Overeating/Binge

Eating (BE), the ordinal character of BE was accounted for.

The result was: c

2

Z

1050.94, df

Z

12, p

Z

0.0001 and hence the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating a significant difference between the samples. This means that separate assessment of both samples is not only justified but also a statistical necessity.

First, descriptive analyses were conducted to gather information about the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the model variables. Second, a crosssectional design was used in conjunction with a structural equation model (SEM), which consisted of theory-based factor analyses (termed the measurement model) and multiple regression analyses (termed the structural model) simultaneously. LISREL 8.52 (

Jo¨reskog and So¨rbom, 1996 ) and

Mplus 8.12 (

Muthe´n and Muthe´n, 2002 ) were used for model

testing. We tested the initial model depicted in

in both samples. We used drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction as measures of the latent construct low body esteem. Negative affect (NA) was assessed by using scores on the SCL subscales depression and anxiety (for the rationale and details of these latent constructs, we refer to the Results section). After testing the initial model, we tested a second model in which we included lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating as intermediating variables between

3

Stice, Fisher, and Lowe (2004)

questioned the validity of the DEBQ restraint scale on the basis of outcomes of studies using unobtrusive measures for food intake, but this conclusion has been refuted by Van Strien, Engels, Van

Staveren and Herman (in press). First, food intake was measured only at one moment in time and this is at variance with both the fundamentals of valid dietary assessment and the concept of restraint as a trait. Second, measurement of food intake thus measured may not reflect restriction of food intake, i.e.

eating less than desired. Instead, Van Strien et al. (in press) showed that the conclusion that some scales have some validity for actual restriction of food intake seems far more plausible.

Descriptive analyses

For the sample of female adolescents, means and standard deviations were computed for all model variables ( eating in their lives.

). In general, girls scored moderately on body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Further, low scores were found on depression and anxiety, indicating that this sample was relatively well adjusted. Low scores were found on interoceptive awareness, restrained eating, and emotional eating.

Concerning overeating/binge eating 313 adolescents (72%) indicated that they never had an episode of overeating/binge

For the clinical sample, the patients scored high on body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness; many patients reported to be very unhappy with their bodies and to have a strong urge to be thin. In addition, a substantial number of patients suffered from feelings of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, they scored high on restrained eating suggesting a robust pattern of dieting and their high scores on emotional eating suggested that they often ate to deal with negative feelings. Concerning binge eating, a totally different pattern emerged compared with the student sample. Only 92 (28%) patients indicated they never had an episode of binge eating, whereas 100 (31%) patients were involved in binge eating on a daily basis.

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 209

Table 2

Correlations between model variables

Body dissatisfaction (BD)

Drive for thinness (DT)

Depression (DE)

Anxiety (AN)

Lack of interoceptive awareness (IA)

Restrained eating (RE)

Emotional eating (EE)

Overeating/binge eating (BE)

1

–

0.71

0.27

0.22

0.25

0.59

0.18

0.12

2

0.70

–

0.30

0.18

0.29

0.73

0.29

0.13

3

0.35

0.38

–

0.78

0.52

0.19

0.27

0.24

4

0.28

0.30

0.78

–

0.47

0.12

0.23

0.26

5

0.30

0.36

0.55

0.55

–

0.23

0.24

0.14

6

0.43

0.60

0.09

0.04

0.32

–

0.27

0.05

7

0.11

0.22

0.26

0.22

0.24

K

0.04

–

0.21

8

0.11

0.18

0.07

0.04

0.23

K

0.13

0.71

–

Student sample is depicted below the diagonal and clinical sample above the diagonal. For the student sample ( N Z 436) the correlation r is significant at the 5% level

(two-tailed) if r O 0.094. For the clinical sample ( N Z 332) the correlation r is significant at the 5% level (two-tailed) if r O 0.108.

There were strong differences in the distribution of the model variables between the adolescent and clinical sample

(

, for all variables: p !

0.0001). Girls with eating disorders scored higher on body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness, reported more emotional problems as described by feelings of anxiety and depression and scored higher on lack of interoceptive awareness. Next, they dieted more, frequently ate more because of emotional problems, and were more involved in binge eating.

Correlations between model variables anxiety and depression were highly correlated in the samples

(

Drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction as well as

). For the structural equation modelling analyses we used the scores on these scales to form latent constructs.

Furthermore, it appeared that drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction were related to stronger feelings of depression and anxiety, higher lack of interoceptive awareness, to higher scores on restrained and emotional eating, and to higher scores on binge eating in both samples. Those who reported feelings of depression and anxiety were more likely to be less aware of their inner feelings, were more likely to eat because of negative emotions, and were more likely to be engaged in overeating/ binge eating (only for students). Lack of interoceptive awareness was related to higher levels of overeating/binge eating in both samples. Restrained eating, however, was not related to overeating/binge eating in the student sample and showed a marginally negative relationship to overeating/binge eating in the clinical sample. Finally, higher levels of emotional eating were even stronger associated with overeating/binge eating ( r (436)

Z

0.713) in the clinical sample than in the student sample ( r (332)

Z

0.210).

affect were related to enhanced levels of overeating/binge eating. Restrained eating was not related to overeating/binge eating in the female sample. Overall, concerning the test of the dual pathway model, our findings support the assumption that negative affect mediates the link between body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness on the one hand and overeating/binge eating on the other.

We tested a second model in which interoceptive awareness and emotional eating explains the link between negative affect and overeating/binge eating. This model fitted the data well, c

2

Z

23.49 with 10 degrees of freedom ( p

Z

0.01, CFI

Z

0.952,

TLI

Z

0.971, RMSEA

Z

0.06) and the model variables explained 12% in the variance of overeating/binge eating

(

Fig. 2 ). Negative affect was strongly related to interoceptive

awareness and moderately related to emotional eating.

However, interoceptive awareness was not associated with emotional eating. In turn, emotional eating appeared to be related to overeating/binge eating. Although negative affect was related to emotional eating, it was also directly related to overeating/binge eating.

Since the set of variables differ in the two models, no direct comparison was possible. Alternatives, in which

is considered a special case of

with a number of effects fixed to zero, are not fair since the additional variables are correlated mutually and correlated to the other variables and these correlations contribute to the c

2 when they should not.

However, the two models showed too little difference in the variance that they could explain overeating/binge eating (9% versus 12%). So, for female adolescents the more parsimonious model by Stice might apply, although the present study showed no support for the pathway of restrained eating (

Structural models for the clinical sample

Structural models for the sample of female adolescents

The initial model fitted the data well: degrees of freedom (

RMSEA

Z p

Z

0.02, CFI

Z c

2

Z

12.13 with 4

0.966, TLI

Z

0.958,

0.07). It appeared that 9% of the variance in overeating/binge eating could be explained by the model

variables ( Fig. 1 ). Low body esteem, assessed by the scales

drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction, was strongly related to dietary restraint and to negative affect (feelings of depression and anxiety). Further, higher scores on negative

The initial model by Stice did not fit the data, c

2

Z

28.17

with 3 degrees of freedom ( p

Z

0.00, CFI

Z

0.828, TLI

Z

0.714,

RMSEA

Z

0.16). Therefore, it appeared that we were not able to replicate the dual pathway model in our clinical sample.

4

4

The fit of the initial model could be substantially improved by adding a direct path between body image and binge eating ( c

2

(4, N

Z

332)

Z

7.74

, p

Z

0.

10, CFI

Z

0.975, TLI

Z

0.968, RMSEA

Z

.05). Because this is not in line with the dual pathway model, we did not present these model parameters.

210 T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 restraint eating

.81

.03

ns

.76

body low body esteem dissatisfaction

.90

drive for thinness

.32

.16

negative affect

.23

interoceptive awareness

.16

.51

.08

ns

.24

emotional eating

.96

.81

depression anxiety

.18

overeating

We tested a second model in which interoceptive awareness and emotional eating would explain the links between negative affect and overeating/binge eating. This model fitted the data satisfactory, c

2

Z

22.06 with 7 degrees of freedom ( p

Z

0.01,

CFI

Z

0.939, TLI

Z

0.930, RMSEA

Z

0.08) and the model variables explained 61% in the variance of overeating/binge eating (

Fig. 3 ). In this model interoceptive awareness and

emotional eating were related to overeating/binge eating, negative affect was associated with interoceptive awareness.

The most significant difference with the model for the adolescent sample was the strong association between emotional eating and overeating/binge eating. Further, restrained eating was not associated with overeating/binge eating. Therefore, in the clinical sample, the results suggested that drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction were linked to negative affect and lack of interoceptive awareness. Negative affect was related to lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating was strongly associated with episodes of overeating/binge eating.

Discussion

Fig. 2. Extended dual pathway model: student sample.

In the sample of female adolescents, the model by

,

) fitted the data well and the extended model fitted

the data even better. In the clinical sample, however, the initial model by Stice did not fit the data and only the extended, second model showed a satisfactory fit. In both samples there was strong support for a link between negative body image and restrained eating, but in neither of the samples support was found for a link between restrained eating and overeating/binge eating. This implies that the restraint pathway was neither supported in the sample of female adolescents, nor in the sample of female eating disorder patients. Instead, there was strong support for the pathway of negative affect in both samples. The two samples strongly differed with regard to the specific variables that constituted the pathway of negative affect. The strongest difference was the strong association between emotional eating and overeating/binge eating in the clinical sample and the presence of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating as intervening variables between negative affect and overeating/binge eating in this sample. In contrast, in the sample of female students, the association between emotional eating and overeating/binge eating was, although significant, not very strong. An additional difference was that lack of interoceptive awareness, while strongly related to negative affect, did not fully explain the relation between negative affect and emotional eating. Finally, there was also restrained eating

.61

ns

–.07

.74

body low body esteem dissatisfaction

.95

drive for thinness

.43

.14

.19

.95

negative affect

.82

interoceptivev awareness

.50

.18

depression anxiety emotional eating

.77

overeating

Fig. 3. Extended dual pathway model: clinical sample.

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213 a direct link between negative affect and overeating/binge eating in this sample.

(

The satisfactory fit of the initial model by Stice in the sample of female students is consistent with outcomes of other studies using non-clinical samples (e.g.

Ricciardelli, 1998 ; Stice, Nemoroff, and Show, 1996

). Yet, it should be stressed that we found substantially lower estimates of explained variance in our study. In the study by

on 257 female undergraduates the model explained more than 70% in binge eating symptoms, whereas in the present sample of female adolescents it explained only 9% of the variance in overeating/binge eating. A further important difference was that in both the study by

as well as in the study by

Shepherd and Ricchiardelli (1998)

support was obtained for a significant link between restrained and binge eating (see also

).

The difference in outcomes between the studies cannot be easily interpreted, since the studies used different measures for restrained eating and bulimic pathology (

Shafran, 2003 ). As mentioned in the Methods section, our

measurement of binge eating does not assess whether the person experienced a sense of loss of control, an essential aspect of DSM-IV binge eating. Regarding restrained eating,

Shepherd and Ricchiardelli (1998)

showed that the measure for assessment of restraint may affect the study outcome, as restraint, when measured by the restraint scale of the TFEQ, was found to be a weaker mediator between body dissatisfaction and bulimic behaviour than when measured with the

Restraint Scale. This finding is consistent with the suggestion that the Restraint Scale may show bias for the selection of unsuccessful dieters (see also

;

Allison, Kalinsky, and Gorman,

Heatherton, Herman, Polivy, King, and McGree, 1988

Van Strien, 1999 and Ricchiardelli, 1998

, p. 350).

5 by

, the DEBQ measured restrained eating and thus it found significant associations with bulimic pathology. Future research should reveal (1) whether there are strong differences in mean levels of restrained eating and bulimic symptoms in the US and old Western-Europe countries, (2) when using identical measurements, whether model parameters are similar

Ricchiardelli this may also hold true for the measure of restraint used by

: the Diet Factor of the

Eating Attitudes Test ( Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, and Garfinkel,

) and the Weight Control scale from the BULIT-R

Thelen, Farmer, Wonderlich, and Smith, 1991

, see

On the other hand, in a study

5

It should be noted that post hoc analysis of a different assessment of dieting, e.g. ‘Are you currently on a weight loss diet (Yes/No)’ affected the findings in the present sample of female adolescents related to the association between restrained eating and binge eating. In this sample, with a percentage of 17.5% weight loss dieters, a significant but small negative relation between restrained and binge eating was found ( r Z

K

.158, p !

0.001). This indicates that females who were currently dieting had more attacks of binge eating, than those who did not currently diet. In contrast, in the sample of eating disorder patients, although 55% of these females alleged to be currently on a weight loss diet, there was no relation between being currently on a diet and binge eating ( r

Z

0.

021, ns).

211 or dissimilar between cultures, and (3) why robust differences appear in model parameters.

In the clinical sample, restrained eating was not associated with binge eating, even with a different measure of restraint, which indeed indicated the absence of support for the restraint pathway in this sample. This result is, nevertheless, in agreement with results of several other studies on case-rich or clinical samples, in which relations between restraint and binge eating were also absent or even negative (

Lowe, Gleaves, and Murphy-Eberentz, 1998 , a

reanalysis of the

study (in

, p. 131, see also

Decaluwe´, 2003 , Chapter 6). According to

Stice (2001) , this opens the possibility that dieting may play a

more important role in the development than the maintenance of binge eating, which would explain that several longitudinal samples of adolescents did reveal significant links between

dieting and binge eating ( Fairburn, Stice, Cooper, Doll,

typically emerges in middle adolescence. Additionally, the different pattern of findings in relation to the various measures for the assessment of restraint may call for further research into the role of different forms of dietary restraint in the aetiology of binge eating, e.g. whether dieting involves flexible versus rigid

control of eating behaviours ( Shaerin, Russ, Hull, Clarkin, and

;

Westenhoeven, Broeckman, Mu¨nch, and Pudel,

) or whether it involves a temporary weight loss diet versus chronic restraint in eating behaviour. Further, to investigate the possibility that dieting is linked to bulimic behaviour only in a subgroup of dieters, i.e. those who combine dieting with a tendency towards overeating (

it seems of importance that also tendency towards overeating is taken into account, as this variable may to a great extent heighten up any relation between measures for restrained and binge eating (see also

Hays, Bathalon, McCrory, Roubenoff,

;

,

Strien, Engels, Van Staveren, and Herman, in press

).

In the clinical sample, only the second model fitted the data and the variables in the model explained more than 60% of the variance in overeating/binge eating. Our findings indicate that the association between negative affect and binge eating was, particularly in this sample, partly explained by interoceptive awareness and emotional eating. This implies support for an individual difference model of distress and overeating (

Schachter, Goldman, and Gordon, 1968 ). The

high explained variance in binge eating suggests the extension of the negative affect pathway in the eating disorders pathology. As stated before, the normal response to distress is loss of appetite. However, according to

, the confusion and apprehension in recognizing and accurately responding to certain visceral sensations related to hunger and satiety that are tapped by the scale for interoceptive awareness, may result in a pattern of responding to negative moods by food intake: emotional eating. In a longitudinal study on risk variables for disordered eating in adolescents, poor interoceptive awareness was also found to be predictive for the development of binge eating (

Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, and Early-Zald, 1995 ).

212

In the present sample of female students, in contrast, the relationship between negative affect and emotional eating was not mediated by interoceptive awareness. Although further research is needed to scrutinize why there is such a strong difference in the link between emotional eating and overeating/ binge eating in non-clinical and clinical females, this suggest a strong and robust almost automatic link between emotional eating and overeating/binge eating in the maintenance of eating disorders.

In the present study, we found support for the pathway of negative affect in both the sample of female adolescents and the sample of female eating disorder patients. However, the differences with regard to the specific variables that constitute these pathways suggest that there may be a qualitative difference between female students and eating disorder patients

(a difference in kind), instead of a dimensional difference (a difference in degree) as these differences do not seem to represent a continuity (see also

all had a strong theoretical basis (e.g. theories on stress-induced and restraint-induced overeating (

1986;

Polivy and Herman, 1995; Schachter, Goldman, and Gordon,

) may give the reader some confidence in the validity of the present results.

6

both samples also strongly differ in age, so, alternatively, the difference in results may also be explained by this age difference instead of merely patient status.

For female adolescents the more parsimonious model by

Stice may apply, although only weak support was found for the pathway of restrained eating. For patients with eating disorders, however, this model may be too limited and a second model in which the path between negative affect and binge eating is mediated by lack of interoceptive awareness and emotional eating may be more applicable. For definite conclusions, more research is needed, preferably with longitudinal designs. It should be noted further, that it can never be ruled out that there may be other models that fit the data equally well and that essentially one can only reject, not confirm, models by using Structural Equation Modelling.

Hence, one can give only limited support in terms of confirming a model as alternative models can exist and even better explain the data. However, the fact that the tested models

Acknowledgements

Rutger Engels was supported by a fellowship of the Dutch

Organization of Scientific Research during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213

Allison, D. B., Kalinsky, L. B., & Gorman, B. S. (1992). A comparison of the

6 psychometric properties of three measures of dietary restraint.

Psychological Assessment , 3 , 391–398.

It should be noted that we acknowledge the conceptual differences of indicators of the latent construct low body esteem. However, the high correlation between the two indicators in both samples caused us to decide to construct one latent construct for the purpose of this paper.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994).

Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders (DSM IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Association.

Brownell, K. D., & Rodin, J. (1994). The dieting maelstrom. Is it possible and advisable to lose weight?

The American Psychologist , 49 , 781–791.

Bruch, H. (1973).

Eating disorders . New York: Basic Books.

Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., Carter, F. A., & Joyce, P. R. (1997). Initial manifestations of disordered eating behaviour. Dieting versus binging.

International Journal of Eating Disorders , 22 , 195–201.

Byrne, S. M., & McLean, N. J. (2002). The cognitive-behavioral model of bulimia nervosa: A direct evaluation.

International Journal of Eating

Disorders , 31 , 17–31.

Decaluwe´, V. (2003).

Binge eating in obese children and adolescents .

Dissertation University of Gent, Belgium.

Derogatis, L. R. (1977).

The SCL-90 manual I: Scoring, administration and procedures for the SCL-90 . Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometric

Research.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A ‘transdiagnostic’ theory and treatment.

Behaviour

Research and Therapy , 41 , 509–528.

Fairburn, C. G., Stice, E., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., Norman, P. A., & O’Connor,

M. E. (2003). Understanding persistence in bulimia nervosa: A fiveyear naturalistic study.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 71 ,

103–109.

Garner, D. M. (1991).

Eating disorder inventory-2 manual . Odessa, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources.

Garner, D. M., Olmstead, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates.

Psychological

Medicine , 12 , 871–878.

Gleaves, D. H., Lowe, M. R., Snow, A. C., Green, B. A., & Murphy-Eberenz,

K. P. (2000). Continuity and discontinuity models of bulimia nervosa. A taxometric investigation.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 109 , 56–68.

Greeno, C. G., & Wing, R. R. (1994). Stress-induced eating.

Psychological

Bulletin , 115 , 444–464.

Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review.

International Journal of Eating Disorders , 31 , 1–16.

Hays, N. P., Bathalon, G. P., McCrory, M. A., Roubenhoff, R., Lipman, R., &

Roberts, S. B. (2002). Eating behavior correlates of adult weight gain and obesity in healthy women aged 55–65 y.

American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition , 75 , 476–483.

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as escape from selfawareness.

Psychological Bulletin , 110 , 86–108.

Heatherton, T. F., Herman, C. P., Polivy, J., King, G. A., & McGree, S. T.

(1988). The (mis)measurement of restraint: An analysis of conceptual and psychometric issues.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 97 , 19–28.

Herman, C. P., & Mack, D. (1975). Restrained and unrestrained eating.

Journal of Personality , 43 , 647–660.

Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1980). Restrained eating. In A. J. Stunkard (Ed.),

Obesity (pp. 208–225). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

Herman, C. P., Polivy, J., & Esses, V. M. (1987). The illusion of counterregulation.

Appetite , 9 , 161–169.

Howard, C. E., & Porzelius, L. K. (1999). The role of dieting in binge eating disorder: Etiology and treatment implications.

Clinical Psychology Review ,

19 , 25–44.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.

Structural

Equation Modelling , 6 , 1–55.

Jansen, A., Oosterlaan, J., Merckelbach, H., & Hout, M. v. d. (1988).

Nonregulation of food intake in restrained, emotional and external eaters.

Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment , 10 , 345–354.

Jo¨reskog, K. G., & So¨rbom, D. (1996).

Lisrel 8: User’s reference guide .

Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc..

Leon, G. R., Fulkerson, J. A., Perry, C. L., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Personality and behavioural vulnerabilities associated with risk status for eating disorders in adolescent girls.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 102 ,

438–444.

T.V. Strien et al. / Appetite 45 (2005) 205–213

Leon, G. R., Fulkerson, J. A., Perry, C. L., & Early-Zald, M. B. (1995).

Prospective analysis of personality and behavioural vulnerabilities and gender influences in the later development of disordered eating.

Journal of

Abnormal Psychology , 104 , 140–149.

Lowe, M. R. (1993). The effects of dieting on eating behaviour: A three-factor model.

Psychological Bulletin , 114 , 100–121.

Lowe, M. R. (2002). Dietary restraint and overeating. In C. G. Fairburn, &

K. D. Brownell (Eds.), Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 88–97). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lowe, M. R., Gleaves, D. H., & Murphy-Eberenz, K. P. (1998). On the relation of dieting and binge eating in bulimia nervosa.

Journal of Abnormal

Psychology , 107 , 263–271.

Lowe, M. R., & Kleifield, E. I. (1988). Cognitive restraint, weight suppression and the regulation of eating.

Appetite , 10 , 159–168.

Lowe, M. R., & Maycock, B. (1988). Restraint, disinhibition, hunger and negative affect eating.

Addictive Behaviors , 13 , 369–377.

Mussel, M. P., Mitchell, J. E., Fenna, C. J., Crosby, R. D., Miller, J. P., &

Hoberman, H. M. (1997). A comparison of onset of binge eating versus dieting in the development of bulimia nervosa.

International Journal of

Eating Disorders , 21 , 353–360.

Muthe´n, L. K., & Muthe´n, B. O. (2002).

Mplus user’s guide . Los Angeles, CA:

Muthe´n & Muthe´n.

Ouwens, M. A., Van Strien, T., & Van der Staak, C. P. F. (2003a). Tendency toward overeating and restraint as predictors of food consumption.

Appetite ,

40 , 291–298.

Ouwens, M. A., Van Strien, T., & Van der Staak, C. P. F. (2003b). Absence of a disinhibition effect of alcohol on food consumption.

Eating Behaviors , 4 ,

323–332.

Polivy, J., Heatherton, T. F., & Herman, C. P. (1988). Self-esteem, restraint and eating behaviour.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 97 , 354–356.

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1985). Dieting and binging: A causal analysis.

American Psychologist , 40 , 194–201.

Presnell, K., & Stice, E. (2003). An experimental test of the effect of weightloss dieting on bulimic pathology: Tipping the scales in a different direction.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology , 112 , 166–170.

Pudel, V., & Westenhoefer, J. (1989).

Vier-Jahreszeiten Kur. Eine rechnergestu¨tzte Strategie zur Beeinflussung des Erna¨hrungsverhaltens und zur Gewichtsreduction. Forschungsbericht zur Entwicklung und

Evaluation . Go¨ttingen: Ena¨hrungspsychologische Forschungsstelle der

Universita¨t.

Schachter, S., Goldman, R., & Gordon, A. (1968). Effects of fear, food deprivation and obesity on eating.

Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology , 10 , 91–97.

Schoemaker, C., van Strien, T., & Van der Staak, C. (1994). Validation of the eating disorders inventory in a nonclinical population using transformed and untransformed responses.

International Journal of Eating Disorders ,

15 , 387–393.

Shaerin, E. N., Russ, M. J., Hull, J. W., Clarkin, J. F., & Smith, G. P. (1994).

Construct validity of the three-factor eating questionnaire. Flexible and rigid control subscales.

International Journal of Eating Disorders ,

16 , 187–198.

Shepherd, H., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (1998). Test of Stice’s dual pathway model:

Dietary restraint and negative affect as mediators of bulimic behaviour.

Behaviour Research and Therapy , 36 , 345–352.

Stice, E. (1994). A review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa and an exploration of the mechanisms of action.

Clinical

Psychology Review , 14 , 633–661.

Stice, E. (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect.

Journal of

Abnormal Psychology , 110 , 124–135.

213

Stice, E., & Agras, W. S. (1998). Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviours during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis.

Behaviour Therapy , 29 , 277–297.

Stice, E., & Agras, W. S. (1999). Sub typing bulimics along dietary restraint and negative affect dimensions.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology , 67 , 460–469.

Stice, E., Fisher, M., & Lowe, M. R. (2004). Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not.

Psychological Assessment , 16 , 51–59.

Stice, E., Nemeroff, C., & Shaw, H. E. (1996). Test of the dual pathway model of bulimia nervosa: Evidence for dietary restraint and affect regulation mechanisms.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 15 , 340–363.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. (1994). Adverse effects of the media portrayed thin-ideal on women, and linkages to bulimic symptomatology.

Journal of Social and

Clinical Psychology , 13 , 288–308.

Stunkard, A. J., & Messick, S. (1985). The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger.

Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 29 , 71–84.

Thelen, M. H., Farmer, J., Wonderlich, S., & Smith, M. (1991). A revision of the bulimia test: The BULIT-R.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology , 3 , 119–124.

Tiggeman, M. (1994). Gender differences in the interrelationships between weight dissatisfaction, restraint and self-esteem.

Sex Roles , 30 , 319–330.

Van Strien, T. (1989). Dieting, dissatisfaction with figure and sex role orientation in women.

International Journal of Eating Disorders , 8 ,

455–462.

Van Strien, T. (1996). On the relationship between dieting and obese and bulimic eating patterns.

International Journal of Eating Disorders ,

19 , 83–92.

Van Strien, T. (1997). Are most dieters unsuccessful? An alternative interpretation of the confound of success and failure in the measurement of restraint.

European Journal of Psychological Assessment , 13 , 186–194.

Van Strien, T. (1999). Success and failure in the measurement of restraint.

Notes and data.

International Journal of Eating Disorders , 25 , 441–449.

Van Strien, T. (2002).

Dutch eating behaviour questionnaire (DEBQ). Manual .

Bury St. Edmunds: Thames Valley Test Company Ltd.

Van Strien, T., Cleven, A., & Schippers, G. M. (2000). Restraint, tendency toward overeating and ice-cream consumption.

International Journal of

Eating Disorders , 28 , 333–338.

Van Strien, T., Engels, R. C. M. E., Van Staveren, W., & Herman, C. P. (in press). The validity of dietary restraint scales: A response to Stice, Fisher and Lowe.

Psychological Assessment .

Van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E. R., Bergers, G. P. A., & Defares, P. B. (1986). The

Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional and external eating behaviour.

International Journal of Eating Disorders , 5 , 295–315.

Van Strien, T., & Ouwens, M. (2003). Validation of the Dutch EDI-2 in one clinical and two nonclinical populations.

European Journal of Psychological Assessment , 19 , 66–84.

Wardle, J., & Beales, S. (1987). Restraint and food intake: An experimental study of eating patterns in the laboratory and in everyday life.

Behavioural

Research and Therapy , 25 , 179–185.

Westenhoefer, J. (1991). Dietary restraint and disinhibition: Is restraint a homogeneous construct?

Appetite , 16 , 45–55.

Westenhoefer, J., Broeckman, P., Munch, A., & Pudel, V. (1994). Cognitive control of eating behaviour and the disinhibition effect.

Appetite , 23 , 27–41.

Yu, C.-Y., & Muthe´n, B. (2001).

Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes . Technical report in preparation.