Teaching Mexican American History

advertisement

Roberto R. Trevino

Teaching Mexican

American History

W

hen 1 was teaching high school in the 1970s I could always

count on getting the right answer when I asked my students

to identify Cesar Chavez, Today when I ask teens the same

question I get a lot of blank stares—and once someone blurted out,

"Oh, isn't he that famous boxer (referring to the hugely popular former

champion from Mexico, Julio Cesar Chavez)!" A generation removed

from the Chicano civil rights era, many of our high school students

today have no idea who the really heroic Cesar was—the labor organizer and champion of justice for farm v^forkers. Moreover, younger

students today. Latinos and non-Latinos alike, have little if any exposure to the history ofthe largest Latino group in the United States,

Mexican Americans.

Given the growing importance of Mexican Americans and other

Latinos in our country today and in its future, it behooves all of us to

better understand their history as part of our common historical experience. I tell students in my classes that what I vi'ant most for them

to take away from my courses is enough knowledge about Mexican

Americans in relation to other Americans so that they can better understand a television newscast or newspaper story dealing with Mexican

American issues. I want them to know how ethnic Mexicans have experienced life in the United States in the past so that they can better understand what makes today's Mexican Americans "tick." In that

spirit 1 want to discuss some central themes in Mexican American history that secondary and college teachers might incorporate into their

teaching ofthe history ofthe American West: land loss, migration, and

the Chicano movement.

There is no issue more important for understanding the Mexican

American experience than land loss. Had Mexican Americans retained

control ofthe millions of acres of land they lost to Anglo-Americans af

ter the war with Mexico ended in 1848, we might all be living in a very

different kind of United States today. After all, in the mid-nineteenth

century, land not only was the greatest source of wealth but also rooted

in it, of course, were social status and the economic power and political influence to maintain it over generations. Uke many ofthe less

savory aspects of American history, there has been a tendency to gloss

over this sensitive, yet vital, aspect of history. How can we more fully

explain to students how Mexican Americans became and largely have

remained economically and politically powerless throughout their history if we do not treat dispossession as something more than "the fortunes of war," as too often has been the case?

i8 OAH Magazine of History * November 2005

This is not a call for teachers to embrace an uncritical historical revisionism for the sake of political correctness—it is simply a challenge

to engage students in more substantive discussions of important issues

based on critical use of readily available scholarship and other strategies.

Chicano historical studies {produced mostly, but not only, by Mexican

Americans) have matured past the point of simphstic "us versus them"

interpretations ofthe past (i). Unlike thirty years ago when ! was desperately looking for any materials in order to teach a high school survey course in Mexican American history, today teachers can count on a

sophisticated and increasingly diverse body of historical scholarship to

deepen their understanding of any number of issues in Mexican American history. Take my earlier question about Mexican Americans' enduring

powerlessness. No one has deah with that query more convincingly (and

even-handedly) than Albert Camarillo in his book Chicanos in a Changing Society (1979). Giving race due consideration while also establishing

the importance of economic factors and other developments that shaped

post-Mexican War California, Camarillo convincingly explains how it

came to be that generations of Mexican Americans became "stuck" in

a lower social status. With equal sophistication, David Montejano's Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas (1987) significantly revamped

our understanding of Mexican Americans in Texas, His book offers a

race/class analysis that paints a more complicated picture of what it has

been like to be Mexican in Texas, including why some Mexican Americans were more successful in some parts ofthe state than in others and

how changing economic developments as well as shifting racial attitudes

molded those experiences.

I am not suggesting high school teachers assign these books to

their students, although excerpts may ceriainly be appropriate for advanced classes. But these are classics in Chicano history and should

be essential summer reading for teachers who can master their arguments and distill them for students as a segue into class discussions.

As for student readings, short primary documents work best for the

nineteenth century. A well-chosen letter, diary entry, or newspaper article really can turn students on to history! Students are much more apt

to feel the effects of Mexican American land loss when they read about

it in the words of someone who experienced it than when they read or

hear it second-hand. Consequently, they are more "primed" for discussion than they might otherwise be. Here again, we are fortunate to have

good published sources from which to choose appropriate short readings of actual voices from the past. David Weber's collection of primary

documents. Foreigners in Their Native Land (1973), has been around for

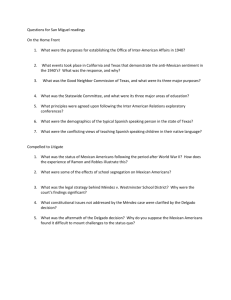

Map of U,S, Territorial Growth, 1830, All ofthe territory in orange was part of Mexico in 1830, (I mage courtesy of Images of American Political History,

<http://teachpol,tcnj.edu/amer_poLhist/_browse_maps,htm>,)

many years and is still very useful. More recently the volume Major

Prohlems in Mexican American History (1999), edited by Zaragosa Vargas, is also an excellent resource.

Along with land loss it is vital to understand the role migration

has played in Mexican American history. Here the central point is that,

although we are a nation of immigrants, not all immigrant experiences

are the same, and we should not expect to understand Mexican immigration and incorporation into the United States by thinking of it

in terms ofthe traditional European model. Indeed, some ofthe differences would seem obvious—no ocean separates the countries, and

Mexicans were first incorporated through wars—or as the saying goes,

"The border crossed us; we did not cross the border." Furthermore,

racism has dogged Mexican immigrants (and native-bom) far longer

and more virulently than it did any European group that at some given

time suffered from American anti-immigrant hysteria and nativism.

Still, most historians and the general public alike mistakenly continue

to try to make sense of Mexican immigration by comparing it to the

European experience.

In the absence of a full-blown survey of Mexican immigration,

teachers can get good insights into this issue from the book by George

Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American (1993), and also from his journal article, "Race, Nation, and Culture in Recent Immigration Studies"

(2), To spice up the topic for students, teachers can use excerpts from

interviews conducted by the pioneering Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio in the early twentieth century. His volume. The Lift Story of

the Mexican Immigrant (1931), offers excellent vignettes told not only

by immigrants but also by native-born Mexican Americans (3). Many

Mexican American students will easily relate to these narratives given

their own experiences or those of relatives and friends, and because of

the current prominence of the immigration issue. Tensions between

native-bom and immigrants swirl uncomfortably around us today, as

they have historically, and they are present in any school as well. When

approached with sensitivity and engaging short readings, the study of

Mexican American immigration history offers a golden opportunity to

educate all our students about an important contemporary issue.

The topic of immigration from Mexico overlaps with internal migration by native-born Mexican Americans, The pattern of leaving

school early in spring and registering late in fall because of migrant

farm work is a well-known aspect ofthe Mexican American experience,

but it is something we usually hear about only in a negative light—in

talking about Mexican American poverty, family instability, and educational underachievement. What about the many stories of triumph that

arise from that same setting.' It is important for students to leam about

the harsh realities of oppression Mexican American have faced, but it

is also important that they hear other equally real stories of success.

In practically any Mexican American community today, there are men

and women who have left behind the migrant stream or other forms

of poverty and built very successful and enviable lives. Teachers should

invite some of those everyday heroes into their classrooms to share

their experiences, or assign students to conduct oral history interviews

in their own communities.

Students can also explore the migrant world through a number

of published accounts suitable for them. One engrossing story is the

highly acclaimed short novel (published in bilingual format), y no se

lo trago la tierra/And ihe Earth Did Not Part {1971), by Tomas Rivera.

More recently, Elva Trevino Hart has poignantly revealed some ofthe

struggles of migrant women through her highly accessible autobiography. Barefoot Heart (1999), As for instructors' readings, historian Sarah

Deutsch significantly enriched our understanding of how gender has

functioned in Mexican American migration and cultural preservation.

OAH Magazine of History • November 200$ 19

Teachers can use her book. No Separate Refuge (1987), to dispel some

phies of Cesar Chavez, the memoirs of Jose Angel Gutierrez and Reies

of the stereotypes about gender roles in Mexican American culture

Lopez Tijerina, the collected speeches of Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales,

and to leam about women's adaptive roles that were crucial in sustainand case studies about different activist organizations and the youth

ing a "regional community" based on labor migration in New Mexico

movement. These are books viritten by people who were intimately inand southern Colorado, Lastly, teachers who want to learn more about

volved in the fight for Chicano civil rights. They give us unique, firstwomen in Mexican American history should look to the work of Vicki

hand perspectives into a critical era in Mexican American history {5).

Ruiz, who has done more than any other historian to promote the study

Luckily, many veterans of these civil rights campaigns live and work

of Mexican American women's struggles for equality (4),

among us; they may be the next-door neighbor, a local doctor, social

Those struggles have a long history, of course, but they burst onto

worker, or lawyer, even the teacher or principal down the hall. And, they

the scene most dramatically and successfully in the 1960s and T970S

are often glad to share their experiences with students in classroom

during the Chicano movement, and are captured in a very useful book

presentations or through interviews. In addition, there are good visual

of short documents by Alma M. Garcia, Chicana Feminist Thought: The

and other materials teachers may use. Nothing captures the attention of

Basic Historical Writings {1997). The Ghicano movement is another

today's students as well as a good video. Particularly effective for learnmajor theme secondary teachers should emphasize. Today, too many

ing and teaching about the Chicano movement is the four-part public

high school graduates have a very limited understanding ofthe U.S.

television series. Chicano! History ofthe Mexican American Civil Rights

civil rights era, associating it narrowly with Martin Luther King Jr. and

Movement (1996). This landmark documentary covers the themes of

the black freedom struggle,

land, labor, educational rerather than with the many

form, and political empowindividuals and groups that

erment and never fails to

also fought for equality in

rivet students' attention and

the sixties and seventies,

ignite discussion. There are

sometimes alongside Afriother good films made durcan

Americans—women,

ing the movement years or

gays. Native Americans,

shortly after, including / am

Asians, and of course ChiJoaquin (1969) and Chicano

canas and Ghicanos, This

Park (1988). Although these

is not meant to detract from

may be more difficult to find,

African American history, to

they are worth searching for

rank the importance of any

in university and large pubpeople's history, or to point

lic libraries. Lastly—with

the finger of blame in any

regard to visual materials—

way. It is simply a reminder

teachers, students, and proof our collective responsibilfessional researchers alike

ity to keep Dr. King's dream

will find a gold mine in the

alive by consciously striving

seventy-seven

videotaped

to leam more about each

interviews conducted by

other. Teachers can play a

Chicano activist-professor

powerful role in this by helpJose Angel Gutierrez and

ing today's young people disreposited at the Special Colcover the larger, more inclulections Department of the

sive meaning of civil rights

Library of the University of

history and its connections

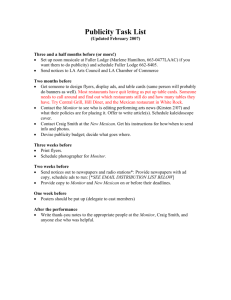

Texas at Arlington. This colNot all Mexican Americans lived the lives ofthe peasantry. Posing for the photographer, this

to their own lives.

lection, Tejano Voices, is fully

Mexican American family demonstrates their middle-class status by their dress. Stories of

Mexican-American successes, as well as incidents of oppression, are effective and important

transcribed and digitized

Far-fetched? Idealistic.^

for easy online access. ReI don't think so. When stu- teaching devices, (Image courtesy ofthe Arizona Historical Society.)

searchers can read the trandents learn that Mexican

scripts

or

listen

to

the

actual

voices

of

these

Mexican American men

Americans have suffered and triumphed and done great and not-soand women as they recount their struggles for civil rights (6).

great things—just like other people—they begin to see them in a different, more positive light. In talks I have given about Mexican American

Clearly, there are other important themes in Mexican American

history to high school students over the years, two ofthe most consishistory I could highlight; these three—land loss, migration, and the

tent reactions I have gotten from non-Latinos (and even sometimes

Chicano movement—are ones I have found students really respond

from Mexican Americans) go something like this: "Oh. I didn't know

to and would seem central to understanding the history of Mexican

they'd had it that bad!" And, "Wow. she was pretty brave; that was cool,

Americans, What is most important is not so much the particular topthe way she stood up!" In a time of increasing uneasiness between

ics teachers choose to include but how they are handled. We know that

African Americans and Latinos, it is our responsibility to find common

students' perceptions about a teacher's fairness and sincerity greatly

ground in our shared history.

affect their openness to learning. Dealing with some ofthe themes sugAgain, teachers can enhance their knowledge and teaching of asgested here, especially through discussion sessions, requires ground

pects of Mexican American civil rights history by tapping into the inrules, as well as a genuinely open and respectful atmosphere. Teachcreasing number of published sources related to the Ghicano moveers should expect emotions to surface—not only anger from Mexican

ment. In recent years several books have appeared about some ofthe

American students who confront disturbing information for the first

major figures and organizations of the movement, including biogratime, but also defensiveness or hostility from non-Mexican Americans.

20 OAH Magazine of History * November 200s

especially whites, for whom these kinds

of discussions may trigger a sense of guilt

or isolation. Both kinds of responses are

normal and should be handled openly and

with appropriate sensitivity so that all students can grow intellectually and emotionally.

What I have called for here is not simply to teach particular aspects of Mexican

American history and integrate them into

the history of the American West. I am

challenging teachers to leave their comfort zones in order to really awaken students to the relevance of history now and

in their future. It is a tall order and easier

said than done, I know. But it is also a

golden opportunity for teachers to make

a real difference. G

Endnotes

1. Alex M, Saragoza, "The Significance of Recent

Chicano-Related Historical Writing: An

Appraisal," Ethnic Affairs i (Fall 1987): 24-62,

2. George J, Sanchez, "Race, Nation, and Culture

in Recent Immigration Studies," JoMma/ of

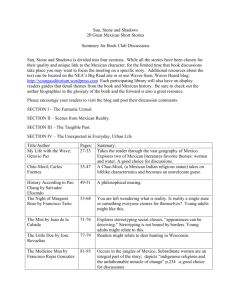

Fr, Antonio Gonzales, Rev, )ames Novarro, and labor organizer Eugene Nelson lead the Minimum Wage March

American Ethnic History 18 (Summer 1999):

staged by striking Texas farm workers in ig66, an event that initiated the Chicano civil rights movement in Texas.

66-84.

(Image courtesy of the Mexican-American Farm Workers Movement Collection, Special Coliections, The Univer3. See also Paul Schuster Tayior. An Americansity of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Arlington, Texas,)

Mexican Frontier. Nueces County. Texas

(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina

Press, 1934).

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003,

4. For example, see Vicki Ruiz, From Out ofthe Shadows: Mexican Women in

Meier, Matt S. and Felidano Rivera, Dictionary of Mexican American History.

Twentieth-Century America (New York; Oxford University Press, 1998),

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981.

5. For starters, see lgnacio M. Garcia, Chicanismo: The Forging of a Militant Ethos

Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1S36-19S6.

Among Mexican Americans (Tucson; University of Arizona Press, 1997);

Austin: University of Texas Press, 1987.

F. Arturo Rosales. Chicano'.: History ofthe Mexican American Civil Rights

Rivera, Tomas, Y no se lo trago ia tierra/And the Earth did not Part. Berkeley, CA:

Movement (Houston: Arie Publico Press, 1997); Carlos Munoz |r.. Youth,

Editorial |usta Publications, 1977.

Identity, Power: The Chicano Movement (London: Verso, 1989); [ose Angel

Rosales, F. Arturo, Chicano,': The History ofthe Mexican American Civil Rights

Gutierrez, The Making of a Chicano Militant: LessonsfromCristal (Madison;

Movement. Houston: Arte Publico Press, 1996.

University of Wisconsin Press, 1998); and Rodolfo "Corky" Conzales,

Sanchez, George ], Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity. Culture, and Identity

Message to Aztldn: Selected Writings of Rodolfo "Corky" Conzates (Houston:

in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Arte Publico Press, 2001).

Vargas, Zaragosa, ed. Major Problems in Mexican American History: Documents

6. The Tejano Voices collection is accessible at <http;//libraries,uta,edu/

and Essays. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Co., 1999.

teianovoices>.

Weber, David J.,ed. Eoreignersin Their Native Land: Historical Roots of the Mexican

References and Resources

Americans. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973.

West, lohn O. Mexican-American Folklore: Legends, Songs, Festivals, Proverbs,

Crafts, Tales of Saints, of Revolutionaries and More. Little Rock, AR: August

House, 1988.

Camarillo, Albert, Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to

American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southem California. 184S-19JO.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

Deutsch, Sarah, No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an AngloAudiovisual Resources

Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880-1^40. New York: Oxford

Chicano!:The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. VHS,

University Press, 1987,

Produced by Sylvia Morales, Susan Racho, Mylene Moreno, and Robert

Gamio, Manuel. The Life Story of the Mexican Immigrant: Autobiographical

Cozens. Los Angeies: National Latino Communications Center and Galan

Documents. Reprint. New York; Dover, 1971, 1931.

Productions, 1996,

Garcia, Alma M,, ed, Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings.

Chicano Park. VHS. Directed by Marilyn Mulford, New York: Cinema Guild,

New York: Routledgo, 1997.

1991,1988,

, The Mexican Americans. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

I Am Joaquin. VHS, Hollywood, CA: CFI, 1995, 1969,

Hart, Flva Treviflo, Barefoot Heart: Stories of a Migrant Child. Tempe, AZ;

Bilingual Press, 1999.

A native tejano, Roberto Trevino worked in the Houston Independent School

Martin, Patricia Preciado. Songs My Mother Sang to Me: An Oral History of

Mexican American Women. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992.

District as a high school history teacher and a coordinator in the Migrant

Matovina, Timothy, and Gerald F, Poyo, eds. Presente!: U.S. Latino Catholicsfrom

Education Program. Having received his Ph.D. in United States history

Colonial Origins to the Present. MaryknoU, NY: Orbis, 2000.

from Stanford, he is currently Associate Professor of History and assistant

Meier, Matt S, Encyclopedia of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement.

director ofthe Center for Mexican American Studies at the University of

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Texas at Arlington.

Meier, Matt S, and Margo Gutierrez. The Mexican American Experience: An Encydopedia.

OAH Magazine of History • November 2005 21