the costs of success: mexican american identity performance within

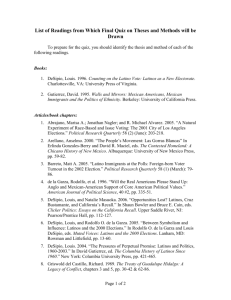

advertisement