precedent, super-precedent

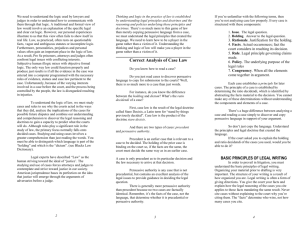

advertisement