3.01 The Northwest Ordinance

advertisement

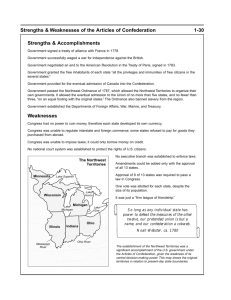

3.01 The Northwest Ordinance From “A Patriot’s History of the United States” by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen [After the Revolutionary War,] Congress immediately set to work on territorial policy, creating legal precedents that the nation follows to this day. Legislators saw the ramifications of their actions with remarkably clear eyes. They dealt with a huge question: if Congress, like the British Parliament before it, established colonies in the West, would they be subservient to the new American mother country or independent? Although the British model was not illogical, Congress rejected it, making the United States the first nation to allow for gradual democratization of its colonial empire. As chair of Congress’s territorial government committee, Thomas Jefferson played a major role in the drafting of the Ordinance of 1784. Jefferson proposed to divide the trans­Appalachian West into sixteen new states, all of which would eventually enter the Union on an equal footing with the thirteen original states. Ever the scientist, Jefferson arranged his new states on a neat grid of latitudinal and longitudinal boundaries and gave them fanciful—classical, patriotic, and Indian— names: Cherroneseus, Metropotamia, Saratoga, Assenisipia, and Sylvania. He directed that the Appalachian Mountains should forever divide the slave from the free states, institutionalizing “free soil” on the western frontier. Although this radical idea did not pass in 1784, it combined with territorial self­governance and equality and became the foundation of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. By 1785, however, Jefferson had left Congress, and nationalists were looking to public lands sales as a source for much­needed revenue. Borrowing the basic policies of northeastern colonial expansion, Congress overlaid the New England township system on the national map. Surveyors were to plot the West into thousands of townships, each containing thirty­six 640–acre sections. Setting aside one section of each township for local school funding, Congress aimed to auction off townships at a rate of two dollars per acre, with no credit offered. Legislators hoped to raise quick revenue in this fashion because only entrepreneurs could afford the minimum purchase, but the system broke down as squatters, speculators, and other wily frontiersmen avoided the provisions and snapped up land faster than the government could survey it. Despite these limitations, the 1785 law set the stage for American land policy, charting a path toward cheap land (scientifically surveyed, with valid title) that would culminate in the Homestead Act of 1862. To this day, an airplane journey over the neatly surveyed, square­cornered townships of the American West proves the legacy of the Confederation Congress’s Land Ordinance of 1785. Congress returned to the territorial government question in a 1787 revision of Jefferson’s Ordinance of 1784. The Northwest Ordinance established a territorial government north of the Ohio River under a governor and judges whom the president chose with legislative approval. Upon reaching a population of five thousand, the landholding white male citizens could elect a legislature and a nonvoting congressional representative. Congress wrote a bill of rights into the Ordinance and stipulated, à la Jefferson’s 1784 proposal, that no slavery or involuntary servitude would be permitted north of the Ohio River. The Ordinance produced other remarkable insights for the preservation of democracy in newly acquired areas. For example, it provided that between three and five new states could be organized from the region, thereby avoiding having either a giant super state or dozens of small states that would dominate the Congress. When any potential state achieved a population of sixty thousand, its citizens were to draft a constitution and apply to Congress for admission into the federal union. During the ensuing decades, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin entered the Union under these terms. The territorial system did not always run smoothly, but it endured. The Southwest Ordinance of 1789 instituted a similar law for the Old Southwest, and Kentucky (1791) and Tennessee (1786) preceded Ohio into the Union. But the central difference remained that Ohio, unlike the southern states, abolished slavery, and thus the Northwest Ordinance joined the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 as the first of the great watersheds in the raging debate over North American slavery. Little appreciated at the time was the moral tone and the inexorability forced on the nation by the ordinance. If slavery was wrong in the territories, was it not wrong everywhere? The relentless logic drove the South to adopt its states’ rights position after the drafting of the Constitution, but the direction was already in place. If slavery was morally right—as Southerners argued—it could not be prohibited in the territories, nor could it be prohibited anywhere else. Thus, from 1787 onward (though few recognized it at the time) the South was committed to the expansion of slavery, not merely its perpetuation where it existed at the time; and this was a moral imperative, not a political one. Popular notions that the Articles of Confederation Congress was a bankrupt do­nothing body that sat by helplessly as the nation slid into turmoil are thus clearly refuted by Congress’s creation of America’s first western policies legislating land sales, interaction with Indians, and territorial governments. Quite the contrary, Congress under the Articles was a legislature that compared favorably to other revolutionary machinery, such as England’s Long Parliament, the French radicals’ Reign of Terror, the Latin American republics of the early 1800s, and more recently, the “legislatures” of the Russian, Chinese, Cuban, and Vietnamese communists. Unlike those bodies, several of which slid into anarchy, the Confederation Congress boasted a strong record. After waging a successful war against Britain, and negotiating the Treaty of Paris, it produced a series of domestic acts that can only be viewed positively. The Congress also benefited from an economy rebuilding from wartime stresses, for which the Congress could claim little credit. Overall, though, the record of the Articles of Confederation Congress must be reevaluated upward, and perhaps significantly so. Answer the following in a 3­5 sentences each: 1. Describe three achievements of the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. 2. Taking in consideration the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, do you agree with the authors’ statement that the government of the Articles “must be reevaluated upward, and perhaps significantly so”? Why or why not?