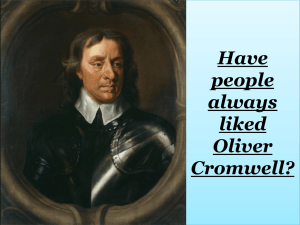

Oliver Cromwell

advertisement

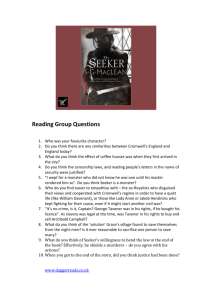

Oliver Cromwell. A Case Study. A Reputation Deserved? The following pages are to be used as supporting material to the textbook that is dedicated to this investigation. 1 The Mark of the Man. Cromwell‘s signature changed over time. The days before fame. Cromwell‘s signature heads a list in the Vestry book of All Saints Church, St. Ives. His signature in a book he owned. His signature now shortened to ―O Cromwell‖. It appears like this on many documents from the civil war era. The mark of Power. The ―P‖ stands for ―Protector‖. 2 The Reputation. Quote 1. From Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon. Clarendon was a supporter of the Royalist cause from 1641 onwards. His daughter married the future James II (son of Charles I). This quote, from his book ―A History of the Great Rebellion‖ was written shortly after Charles II (the eldest son of Charles I). Cromwell was the greatest liar alive. He did great mischief. He forced three countries that hated him to obey his commands and he ruled with an army that was devoted to him. No man with more wickedness ever attempted anything. Quote 2. From C.V Wedgwood, a well respected historian who specialised in the history of the Civil War. She had a particular interest in the life of Charles I. She wrote ―The King‘s Peace‖, ―The King‘s War‖, and ―The Trial of Charles I‖ in the 1950s and 1960s. His [Cromwell’s] cruelty and ruthlessness have left a mark and a memory that the last 300 years have not been able to wipe out. Quote 3. From S. R. Gardiner writing in 1902. Gardiner was a descendent of Cromwell who supported the idea that the seventeenth century saw a Puritan Revolution. [Cromwell] was the national hero…the greatest…the most typical Englishman of all time. 3 Views on Cromwell expressed during the seventeenth century. 4 Why are opinions on Cromwell so divided? B etween 1649 and 1660 England had no monarch. For the first time in its history, the country was a Republic. Nobody really knew how to govern the country without a King. Remember, Parliament had not originally gone to war to rid England of the monarch. The journey to a republic was guided by responses to events between 1646 and 1649. There were many experiments to see what kind of government should replace the monarchy. The most powerful force in the country was the army. So the most powerful person in the country was the one who controlled the army. By 1651, this was Oliver Cromwell. Opinions about Cromwell differed a lot at the time and historians still disagree about him today. Some say that during this period Cromwell tried to grab more and more power for himself. Others say that he was trying to find a better way of governing the country. Some say Cromwell believed in giving people greater freedom. Others say that he crushed anyone who disagreed with him. To help us understand Cromwell‘s actions, we need to see how he dealt with a number of problems facing the government between 1649 and 1660. The Irish Rebellion 1649. T he Irish Catholics had rebelled against English rule in 1641. According to the English, they had committed many brutal and cruel acts. But nothing could be done about the Irish rebellion until the Civil War in England was over. The Catholics in Ireland had supported Charles I‘s son. They thought that he should be King of England and in 1649, the leader of the Irish Catholics, the Marquis of Ormonde, was in France collecting soldiers and weapons. The new Commonwealth government in England feared that Ormonde would launch an attack on England from Ireland. To prevent this, the Commonwealth government sent Cromwell to Ireland with 12,000 troops of the new Model Army. Their first target was the town of Drogheda, which was defended by part of Ormonde‘s army led by Sir Arthur Aston. Aston was an English royalist who had fought for Charles I during the war. Sources 1 to 5 tell us what happened next. 5 6 Source 3. A contemporary English engraving of the final attack on Drogheda. There are two important seventeenth-century rules of warfare that you need to know about: A successful army could give quarter to the enemy. This meant that the enemy would surrender and give up their weapons. When quarter was given, it was wrong to kill, injure or harm the surrendered soldiers in any way. When attacking a town or city, the attacking side would summon the defenders. They would give them the chance to surrender before an attack. If the defenders surrendered there and then, perhaps after some negotiation, then all the defending 7 soldiers would be given quarter. If the defenders did not surrender then they gave up the right to receive quarter from the attacking army. This gave the attackers the right to put to death all those fighting against them. Look back at Sources 2 to 5. Decide which of these accounts are reliable. Was the author an eyewitness? Do other accounts agree with it? Could the author have any reason for not telling the truth? Now look at the two rules of warfare. If events were as Cromwell described, was he justified in doing what he did? Even today, in Ireland, Mothers warn misbehaving children that Cromwell will catch them if they do not behave. What does this tell us about how the Irish remember Cromwell? Cromwell and Parliament. etween 1649 and 1653, England was governed by ―The Rump Parliament‖. This was made up of those MPs that had supported Parliament during the war. There were no Royalist supporting MPs among their number. They had been excluded from returning to the House of Commons. By 1653 these MPs had been sitting for thirteen years. The last election had been held in 1640. B Cromwell had hoped that it would pass reforms to make England a more godly place, and to give Protestants freedom to worship as they wished. He, and others, wanted ―The Rump‖ to organise elections so that a new Parliament could be chosen so that royalist MPs could be replaced and those entitled to vote could choose their government in peacetime. ―The Rump‖ did none of these things. Instead of attempting to dissolve itself, Parliament was making moves to disband the Army. "As for the members of this Parliament," Cromwell said, "the army begins to take them in disgust." Sources 6 and 7 show us how Cromwell, as the Commander of the Army (The Lord General) reacted. Source 6. ―Cromwell and Parliament‖ from ―Historical Tales‖ by Charles Morris, published in 1893. The Parliament of England had defeated and put an end to the king; it remained for Cromwell to put an end to the Parliament. "The Rump," the remnant of the old Parliament was derisively called. What was left of that great body contained little of its honesty and integrity, much of its pride and incompetency. The members remaining had become infected with the wild notion that they were the governing power in England, and instead of preparing to disband themselves they introduced a bill for the disbanding of the army. They had not yet learned of what stuff Oliver Cromwell was made. A bill had been passed, it is true, for the dissolution of the Parliament, but in the discussion of how the "New Representative" was to be chosen it became plainly evident that the members of the Rump intended to form part of it, without the formality of re-election. A struggle for power seemed likely to arise between the Parliament and the army. It could have but one ending, with a man like Oliver 8 Cromwell at the head of the latter. The officers demanded that Parliament should immediately dissolve. The members resolutely refused. Cromwell growled his comments. "As for the members of this Parliament," he said, "the army begins to take them in disgust." There was ground for it, he continued, in their selfish greed, their interference with law and justice, the scandalous lives of many of the members, and, above all, their plain intention to keep themselves in power. "There is little to hope for from such men for a settlement of the nation," he concluded…. … The issue was now sharply drawn between army and Parliament. The officers met and demanded that Parliament should at once dissolve, and let the Council of State manage the new elections. A conference was held between officers and members, at Cromwell's house, on April 19, 1653. It ended in nothing. The members were resolute. "Our charge," said Haslerig, arrogantly, "cannot be transferred to any one." The conference adjourned till the next morning, Sir Harry Vane engaging that no action should be taken till it met again. Yet when it met the next morning the leading members of Parliament were absent, Vane among them. Their absence was suspicious. Were they pushing the bill through the House in defiance of the army? Cromwell was present,—"in plain black clothes, and gray worsted stockings,"—a plain man, but one not safe to trifle with. The officers waited a while for the members. They did not come. Instead there came word that they were in their seats in the House, busily debating the bill that was to make them rulers of the nation without consent of the people, hurrying it rapidly through its several stages. If left alone they would soon make it a law. Then the man who had hurled Charles I from his throne lost his patience. This, in his opinion, had gone far enough. Since it had come to a question whether a self-elected Parliament, or the army to which England owed her freedom, should hold the balance of power, Cromwell was not likely to hesitate. "It is contrary to common honesty!" he broke out, angrily. Leaving Whitehall, he set out for the House of Parliament, bidding a company of musketeers to follow him. He entered quietly, leaving his soldiers outside. The House now contained no more than fifty-three members. Sir Harry Vane was addressing this fragment of a Parliament with a passionate harangue in favor of the bill. Cromwell sat for some time in silence, listening to his speech, his only words being to his neighbour, St. John. "I am come to do what grieves me to the heart," he said. Vane pressed the House to waive its usual forms and pass the bill at once. "The time has come," said Cromwell to Harrison, whom he had beckoned over to him. "Think well," answered Harrison; "it is a dangerous work." 9 The man of fate subsided into silence again. A quarter of an hour more passed. Then the question was put "that this bill do now pass." Cromwell rose, took off his hat, and spoke. His words were strong. Beginning with commendation of the Parliament for what it had done for the public good, he went on to charge the present members with acts of injustice, delays of justice, self-interest, and similar faults, his tone rising higher as he spoke until it had grown very hot and indignant. "Your hour is come; the Lord hath done with you," he added. "It is a strange language, this," cried one of the members, springing up hastily; "unusual this within the walls of Parliament. And from a trusted servant, too; and one whom we have so highly honored; and one—" ―Come, come," cried Cromwell, in the tone in which he would have commanded his army to charge, "we have had enough of this." He strode furiously into the middle of the chamber, clapped on his hat, and exclaimed, "I will put an end to your prating." He continued speaking hotly and rapidly, "stamping the floor with his feet" in his rage, the words rolling from him in a fury. Of these words we only know those with which he ended. "It is not fit that you should sit here any longer! You should give place to better men! You are no Parliament!" came from him in harsh and broken exclamations. "Call them in," he said, briefly, to Harrison. At the word of command a troop of some thirty musketeers marched into the chamber. Grim fellows they were, dogs of war, the men of the Rump could not face this argument; it was force arrayed against law,—or what called itself law,—wrong against wrong, for neither army nor Parliament truly represented the people, though just then the army seemed its most rightful representative. "I say you are no Parliament!" roared the Lord General, hot with anger. "Some of you are drunkards." His eye fell on a bottle-loving member. "Some of you are lewd livers; living in open contempt of God's commandments" His hot gaze flashed on Henry Marten and Sir Peter Wentworth. "Following your own greedy appetites and the devil's commandments; corrupt, unjust persons, scandalous to the profession of the gospel: how can you be a Parliament for God's people? Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God—go!" These words were like bomb shells exploded in the chamber of Parliament. Such a scene had never before and has never since been seen in the House of Commons. The members were all on their feet, some white with terror, some red with indignation. Vane fearlessly faced the irate general. "Your action," he said, hotly, "is against all right and all honor." "Ah, Sir Harry Vane, Sir Harry Vane," retorted Cromwell, bitterly, "you might have prevented all this; but you are a juggler, and have no common honesty. The Lord deliver me from Sir Harry Vane!" The retort was a just one. Vane had attempted to usurp the government. Cromwell turned to the speaker, who obstinately clung to his seat, declaring that he would not yield it except to force. 10 "Fetch him down!" roared the general. "Sir, I will lend you a hand," said Harrison. Speaker Lenthall left the chair. One man could not resist an army. Through the door glided, silent as ghosts, the members of Parliament. "It is you that have forced me to this," said Cromwell, with a shade of regret in his voice. "I have sought the Lord night and day, that He would rather slay me than put upon me the doing of this work." He had, doubtless; he was a man of deep piety and intense bigotry; but the Lord's answer, it is to be feared, came out of the depths of his own consciousness. Men like Cromwell call upon God, but answer for Him themselves. "What shall be done with this bauble?" said the general, lifting the sacred mace, the sign-manual of government by the representatives of the people. "Take it away!" he finished, handing it to a musketeer. His flashing eyes followed the retiring members until they all had left the House. Then the musketeers filed out, followed by Cromwell and Harrison. The door was locked, and the key and mace carried away by Colonel Otley. A few hours afterwards the Council of State, the executive committee of Parliament, was similarly dissolved by the Lord-General, who, in person, bade its members to depart. "We have heard," cried John Bradshaw, one of its members, "what you have done this morning at the House, and in some hours all England will hear it. But you mistake, sir, if you think the Parliament dissolved. No power on earth can dissolve the Parliament but itself, be sure of that." The people did hear it,—and sustained Cromwell in his action. Of the two sets of usurpers, the army and a non-representative Parliament, they preferred the former. "We did not hear a dog bark at their going," said Cromwell, afterwards. It was not the first time in history that the army had overturned representative government. In this case it was not done with the design of establishing a despotism. Cromwell was honest in his purpose of reforming the administration, and establishing a Parliamentary government. But he had to do with intractable elements. He called a constituent convention, giving to it the duty of paving the way to a constitutional Parliament. Instead of this, the convention began the work of reforming the constitution, and proposed such radical changes that the lord-general grew alarmed. Doubtless his musketeers would have dealt with the convention as they had done with the Rump Parliament, had it not fallen to pieces through its own dissensions. It handed back to Cromwell the power it had received from him. He became the lord protector of the realm. The revolutionary government had drifted, despite itself, into a despotism. A despotism it was to remain while Cromwell lived. 11 Source 7. The “Rump” Parliament is dismissed How do Cromwell‘s actions compare to the actions of Charles I? Charles Morris based this story on an eyewitness account of that day in 1653. The words he quotes were actually spoken. What opinion does Morris have of Cromwell? What words or phrases tell us his thoughts? The Lord Protector. ollowing the dissolution of the ―Rump Parliament‖ a newly elected Parliament devised a new constitution. It decided to give a large share of power to the Lord General Cromwell. The new constitution gave Cromwell the title of Lord Protector. This title had been used before in the Reign of Edward VI. The diagram on the next page gives a simple explanation of how the newly devised system of government would work. F The “King”? I n 1654, another new Parliament was elected. Cromwell did not get on with it very well. There was immediate trouble because it wanted to restrict people‘s freedom to worship God how they wished. Cromwell was a committed Independent. He insisted that there should be complete freedom of worship. In 1655, the relationship between Parliament and the Lord Protector had become so bad that Cromwell exercised his power to dismiss Parliament. 12 Cromwell then tried a new experiment. He divided the country into eleven districts each district was run by a Major-General of the Army. This system of government was very unpopular and has led some historians to see Cromwell as a military dictator. Source 10. The Arms of the Commonwealth of England. This was the name by which the government of England was known before Cromwell took up the title of Lord Protector. The arms of the Government changed in 1653. The new arms can be seen in the diagram in Source 11. 13 Source 11. By 1657, many were running out of ideas about how to effectively rule the country. Many of the MPs and country gentry had had enough of the rule of the Army and of the high taxes they were being forced to pay to maintain the Army in peacetime. One of these taxes was imposed without the agreement of a Parliament (Hmm….this sounds oddly familiar). Many people were also worried about the new ideas that were threatening their way of life. Some lower classes were claiming that the land belonged to everyone! Riots were breaking out! New and extreme religious groups were emerging! Where would it end? Many people thought that the only way to bring back law and order and return England to a stable position was to bring back the monarchy. But, they did not want to bring back 14 Charles Stuart (eldest son of Charles I who was in exile on the continent). The only man, it seemed, that could restore order was His Highness the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. In February 1657, a group of MPs formally offered Cromwell the crown! Olivar Rex? The Royal House of Cromwell? Not if the Army had its way! Cromwell, after some time in thought, rejected the offer. But he did accept a new constitution. Under this constitution, his son Richard would become Lord Protector after him and some of the religious freedoms given in previous years would be taken away. There would also be a ceremony, like a coronation, with ermine robes, a crown, orb, scepter and sword of state, to ‗invest‘ or recognize, the Lord Protector as the Head of State. By the end of his life in 1658, Cromwell had so much power and so many of the trappings of royalty that his detractors have called ―King in all but name.‖ 15 Was Cromwell a power hungry despot or a man struggling to act in the best interests of the people of England? Explain your answer. Try to give some reasons, which would explain the answer ―yes‖, and some, which support the answer ―no‖. Then come to a conclusion; say what you think that answer is and why you have chosen that answer. 16 Christmas abolished! Why did Cromwell abolish Christmas? It is a common myth that Cromwell personally ‗banned‘ Christmas during the mid seventeenth century. Instead, it was the broader Godly or parliamentary party, working through and within the elected parliament, which in the 1640s clamped down on the celebration of Christmas and other saints‘ and holy days, a prohibition which remained in force on paper and more fitfully in practice until the Restoration of 1660. There is no sign that Cromwell personally played a particularly large or prominent role in formulating or advancing the various pieces of legislation and other documents which restricted the celebration of Christmas, though from what we know of his faith and beliefs it is likely that he was sympathetic towards and supported such measures, and as Lord Protector from December 1653 until his death in September 1658 he supported the enforcement of the existing measures. The celebration of Christmas in seventeenth century England had many similarities with our own celebrations. Christmas Day itself, 25 December, was marked as a holy day, celebrating and commemorating the birth of Christ, but it also formed the first day of an extended period of celebration and merriment, lasting until early January - the Twelve Days of Christmas. Although the English calendar was not formally brought into line with the Continental calendar until the mid eighteenth century, in the seventeenth century many people in this country already saw 1 January (rather than 25 March) as marking the turning point at which the old year gave way to the new, and New Year‘s day formed another high point of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Twelfth Night, which closed the period of celebration, was often marked by a renewed bout of feasting and carnivals. Christmas Day itself was a public holiday, with shops, offices and other places of work all closed, and people went to church to attend special services; over the following eleven days there were further special church services, with shops and businesses open only intermittently or for shorter hours than normal. The celebration of all Twelve Days of Christmas contained other familiar elements, though the degree to which individuals and families participated probably varied, depending upon whether they were living in London, a large provincial town or deep in the countryside, upon whether they were rich or poor and thus upon how much time and money they could afford to expend on celebrations. Churches, public buildings and private houses were often decorated with holly and ivy, rosemary and bays. People visited family, friends and colleagues, eating and drinking and exchanging presents, and the more affluent distributed ‗boxes‘ containing money to servants, tradesmen and the poor. Special food and drink was available and was consumed in larger quantities than normal, including turkey and beef, mince pies, plum porridge and specially brewed Christmas ale; taverns and taphouses did a roaring trade. Occasionally there were fireworks (though then as now they were more associated with the celebration of the failure of the Gunpowder Treason plot on 5 November), and there was also the concept of a ‗Father Christmas‘, more as a figure that oversaw the community celebrations than as someone who gave presents to children. More generally, it was a period of leisure, of eating and drinking to excess, of dancing and singing, gambling, 17 gaming and stage plays (though modern-style pantomimes did not emerge until the eighteenth century), of drunkenness and sexual immorality, a period when normal rules and self-control did not apply, a period of deliberate inversion and ‗misrule‘. Increasingly in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, many people, especially the more Godly, came to frown upon this celebration of Christmas, for two reasons. Firstly, they disliked all the waste, extravagance, disorder, sin and immorality of the Christmas celebrations. Secondly, they saw Christmas (that is, Christ‘s mass) as an unwelcome survival of the Roman Catholic faith, as a ceremony particularly encouraged by the Catholic church and by the recusant community in England and Wales, a popish festival with no biblical justification – nowhere had God called upon mankind to celebrate Christ‘s nativity in this way, they said. What this group wanted was a much stricter observance of the Lord‘s day (Sundays), but the abolition of the popish and often sinful celebration of Christmas, as well as of Easter, Whitsun and assorted other festivals and saints‘ days. In the early 1640s, as power passed from Charles I (who largely supported the existing rituals and festivals) to the Long Parliament, parliament began the process of clamping down on the celebration of Christmas, pressing that ‗Christtide‘ (as they preferred it called, thus doing away with the ‗mass‘ element and its Catholic echoes) should be kept, if at all, merely as a day of fasting and seeking the Lord. In January 1642, shortly before civil war began, Charles I had agreed to parliament‘s request to order that the last Wednesday in each month should be kept as a fast day; many hoped that Christ-tide, 25 December, would come to be seen and kept as just an addition to these regular fast days. The Long Parliament, in fact, met and worked as usual on 25 December 1643. In late 1644 it was noted that 25 December would fall on the last Wednesday of the month, the day of the regular monthly fast, and parliament stressed that 25 December was strictly to be kept as a time of fasting and humiliation, for remembering the sins of those who in the past had turned the day into a feast, sinfully and wrongfully ‗giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights‘. Both Houses of Parliament attended intense fast sermons on 25 December 1644. In January 1645 a group of ministers appointed by parliament produced a new Directory of Public Worship, which set out a new church organisation and new forms of worship to be adopted and followed in England and Wales. The Directory made clear that Sundays were to be strictly observed as holy days, for the worship of God, but that there were to be no other holy days – ‗festival days, vulgarly called Holy Days, having no warrant in the Word of God, are not to be continued‘. Parliamentary legislation adopting the Directory of Public Worship, initially as one of several forms which could be followed in England and Wales, but then as the only form which was legal and was to be allowed, abolishing and making illegal any other forms of worship and church services, therefore prohibited (on paper at least) the religious celebration of all other holy days, including Christmas. In June 1647 the Long Parliament reiterated this by passing an Ordinance confirming the abolition of the feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun, though at the same time parliament said that the second Tuesday in each 18 month was to be kept as a non-religious, secular holiday, providing a break for servants, apprentices and other employees. During the 1650s parliamentary legislation was passed to reinforce the structure that had been put in place by the end of the 1640s. Specific penalties were to be imposed on anyone found holding or attending a special Christmas church service, it was ordered that shops and markets were to stay open on 25 December, the Lord Mayor was repeatedly ordered to ensure that London stayed open for business on 25 December, and when it met on 25 December 1656 the second Protectorate Parliament discussed the virtues of passing further legislation clamping down on the celebration of Christmas (though no Bill was, in fact, produced). Legislation was passed to ensure that Sundays were even more strictly observed as the Lord‘s Day, but the holding of a regular monthly fast on the last Wednesday of the month, which had never proved popular or been widely followed, was quietly dropped. Although in theory and on paper the celebration of Christmas had been abolished, in practice it seems that many people continued to mark 25 December as a day of religious significance and as a secular holiday. Semi-clandestine religious services marking Christ‘s nativity continued to be held on 25 December, and the secular elements of the day also continued to occur – on 25 December 1656 MPs were unhappy because they had got little sleep the previous night through the noise of their neighbours‘ ‗preparations for this foolish day‘s solemnity‘ and because as they walked in that morning they had seen ‗not a shop open, nor a creature stirring‘ in London. During the late 1640s attempts to prevent public celebrations and to force shops and businesses to stay open had led to violent confrontations between supporters and opponents of Christmas in many towns, including London, Canterbury, Bury St Edmunds and Norwich. Many writers continued to argue in print (usually anonymously) that it was proper to mark Christ‘s birth on 25 December and that the secular government had no right to interfere, and it is likely that in practice many people in mid seventeenth century England and Wales continued to mark both the religious and the secular aspects of the Christmas holiday. At the Restoration not only the Directory of Public Worship but also all the other legislation of the period 1642-60 was declared null and void and swept away, and both the religious and the secular elements of the full Twelve Days of Christmas could once again be celebrated openly, in public and with renewed exuberance and wide popular support. The attack on Christmas had failed. From the Web Pages of The Cromwell Association www.olivercromwell.org 19 In his lifetime, Cromwell said many things. Here are some of my favourite ―Cromwell Soundbites.‖ The Wit and Wisdom of Oliver Cromwell 1599-1658 “I was by birth a gentleman, living neither in any considerable height, nor yet in obscurity. I have been called to several employments in the nation-to serve in parliaments, -and (because I would not be over tedious) I did endeavor to discharge the duty of an honest man in those services, to God, and his people’s interest, and of the commonwealth; having, when time was, a competent acceptation in the hearts of men, and some evidence thereof.” Speech to the first Parliament of the Protectorate, Sept, 1654. “If the remonstrance had been rejected I would have sold all I had the next morning and never have seen England more, and I know there are many other modest men of the same resolution.” Oliver Cromwell on parliament‘s passing of the revolutionary grand remonstrance, quoted in the Earl of Clarendon, A History of the Great Rebellion. “I would rather have a plain russet-coated captain that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and is nothing else.” Letter from Cromwell to Sir William Spring. Sept. 1643. “Truly England and the church of God hath had a great favour from the Lord, in this great victory given us.” Oliver Cromwell on the battle of Marston Moor. 1644. “We study the glory of God, and the honour and liberty of parliament, for which we unaminously fight, without seeking our own interests....I profess I could never satisfy myself on the justness of this war, but from the authority of the parliament to maintain itself in its rights; and in this cause I hope to prove myself an honest man and singlehearted.” Oliver Cromwell to Colonel Valentine Walton. 5 or 6 September 1644. “I could not riding out alone about my business, but smile out to God in praises, in assurance of victory because god would, by things that are not, bring to naught things that are”. Cromwell before the battle of Naseby. 1645. 20 “We declared our intentions to preserve monarchy, and they still are so, unless necessity enforce an alteration. It’s granted the king has broken his trust, yet you are fearful to declare you will make no further addresses. .....look on the people you represent, and break not your trust, and expose not the honest party of your kingdom, who have bled for you, and suffer not misery to fall upon them for want of courage and resolution in you, else the honest people may take such courses as nature dictates to them.” Cromwell‘s speech in the commons during the debate which preceded the ―vote of no addresses‖, recorded in the diary of John Boys, MP for Kent. “Since providence and necessity has cast them upon it, he should pray God to bless their councels.” Cromwell on the trial of King Charles I. Dec. 1648. “I tell you we will cut off his head with the crown upon it.” Cromwell to one of the judges at the trial of King Charles I.1648. “Cruel necessity”. Cromwell on the execution of King Charles I. Jan 1649. “This is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands in so much innocent blood....” Oliver Cromwell after the storming of Drogheda.1649. “I need pity. I know what I feel. Great place and business in the world is not worth looking after.‖ On himself, letter to Richard Mayor, July 1650. “I beseech you in the bowels of Christ think it possible you may be mistaken.” In a letter to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. 1650. “I am neither heir nor executor to Charles Stuart.” On himself, repudiating a royal debt, August 1651. “The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is for aught I know, a crowning mercy.” Letter. 1651. “Take away that fool’s bauble, the mace” Oliver Cromwell speech dismissing the rump parliament. Apr. 1653. 21 “When I went there, I did not think to have done this. But perceiving the spirit of God so strong upon me, I would not consult flesh and blood.” On himself, on his forcible dissolution of parliament in April 1653, “No one rises so high as he who knows not whither he is going.” Cromwell on personal fortunes. “You are as like the forming of God as ever people were...you are at the edge of promises and prophecies.” Cromwell addressing the Barebones Parliament. July 1653 “You have been sat to long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!.” Addressing the Rump Parliament. April 1653. “The people would be just as noisy if they were going to see me hanged.” Cromwell referring to a cheering crowd, 1654 “Weeds and nettles, briars and thorns, have thriven under your shadow, dissettlement and division, discontentment and dissatisfaction, together with real dangers to the whole.” Cromwell‘s speech dissolving the first Protectorate Parliament. “God has brought us where we are, to consider the work we may do in the world, as well as at home.” Cromwell to the Army Council. 1654. “There are some things in this establishment that are fundamental....about which I shall deal plainly with you...the government by a single person and a parliament is a fundamental...and..though I may seem to plead for myself, yet I do not: no, nor can any reasonable man say it. I plead for this nation, and all the honest men therin..” Cromwell to the first Protectorate Parliament, 12 September 1654. ―Necessity hath no law.‖ Speech to Parliament, Sept. 1654. “In every government there must be somewhat fundamental, somewhat like a magna charta, that should be standing and unalterable...that parliaments should not make 22 themselves perpetual is a fundamental.” Cromwell in a speech to the first Protectorate Parliament, 12 September 1654. “I desire not to keep my place in this government an hour longer than I may preserve England in it’s just rights, and may protect the people of god in such a just liberty of their consciences....” Cromwell to the first Protectorate Parliament, 22 January 1655. “(Kingship) is not so interwoven in the laws...truly though the kingship be not a mere title but a name of office that runs through the whole of the law....as such a title hath been fixed, so it may be unfixed...” Cromwell to the representatives of the second Protectorate Parliament, 13 April 1657. “You drew me here to accept the place I now stand in. There is ne’er a man within these walls that can say, sir, you sought it, nay, not a man nor woman treading upon English ground.” Cromwell‘s speech to Parliament, 4 February 1658. “You have accounted yourselves happy on being environed with a great ditch from all the world beside.” In a letter, 1658. “Not what they want but what is good for them.” Remark by Oliver Cromwell. “Mr. Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint your picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughness, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me; otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.” Cromwell on having his portrait painted. “My design is to make what haste I can to be gone.” Cromwell‘s last words. 23 24