Study Unit 1

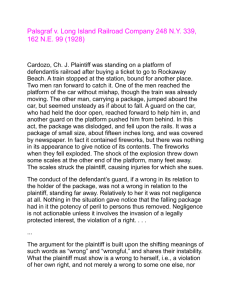

advertisement