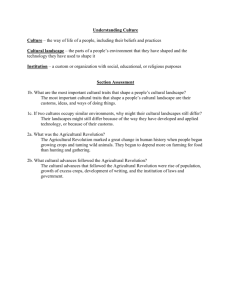

cultural landscapes in conflict: addressing the interests and

advertisement