W. E. B. DU BOIS On African American Identity: “Of Our Spiritual

advertisement

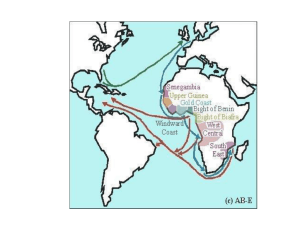

Dr. Richard Clarke LITS3001 Notes 12A 1 W. E. B. DU BOIS On African American Identity: “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” (1897) Dubois is perhaps the most influential figure in African American social and political discourse during the early part of the Twentieth century and one of the earliest to identify himself as a Pan-Africanist. He was one of (if not the) first to pose the question of the African American’s hybridity, that is, the dilemma of being both American and black at the same time. Here, drawing upon Hegel’s notion of the Master/Slave dialectic, he addresses what he describes as the “double consciousness” (102) with which the African American is afflicted, this sense of always looking at one’s self from through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels this twoness,--an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body. (102) The “history of the American Negro is the history of this strife--this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost” (102). “The Conservation of Races” (1897) Here, Du Bois attempts to define what it means to be a negro. His main query concerns the “essential difference of races” (39) and his finding is that a race cannot be defined solely in biological terms: “What, then, is a race?” (40), he asks. It is a “vast family of human beings, generally of common blood and language, always of common history, traditions and impulses” (40). He explains: while race differences have followed mainly physical race lines, yet no mere physical distinctions would really define or explain the deeper differences--the cohesiveness and continuity of these groups. The deeper differences are spiritual, psychical, differences--undoubtedly based on the physical, but infinitely transcending them. The forces that bind together . . . nations are, then, first, their race identity and common blood; secondly, and more important, a common history, common laws and religion, similar habits of thought and a conscious striving together for certain ideals of life. (41) However, Du in attempting to grasp the ethnic identity of African Americans, Bois seems to abandon this culturalist model of identity in favour of a more racialist paradigm. He argues that, although negroes may be American by birth, citizenship, political ideals, language and religion (these are all cultural factors), they are nevertheless still, more importantly, Negroes, members of a vast historic race that from the very dawn of creation has slept, but half awakening in the dark forests of its African fatherland. We are the first fruits of this new nation, the harbinger of that black tomorrow which is yet destined to soften the whiteness of the Teutonic today. (44) It is at least as much to the common biology shared by all negroes as to some ill-defined shared ‘ideal’ that Du Bois seems to appeal: he contends that if the negro race is ever to take its place among the community of races each of which have something original to contribute to human civilisation, it must aim for unity, what Du Bois terms “Pan-Negroism” (43): “only Negroes bound and welded together, inspired by one vast ideal” (my emphasis; 42) can lead to the “development of Negro genius, of Negro literature and art, of Negro spirit” (42). “The Concept of Race” (1940) Here, Du Bois articulates a conceptualisation of African American identity based less on a common biology than a shared history of suffering. Here, he contends that Africa is of course my fatherland. . . . On this vast continent were born and lived a large portion of my direct ancestors going back a thousand years or more. The mark of their heritage is upon me in color and hair. (257) However, what defines him as African is less consanguineity than the fact that Dr. Richard Clarke LITS3001 Notes 12A 2 since the fifteenth century these ancestors of mine and their other descendants have had a common history, have suffered a common disaster, and have one long memory. . . . [T]he physical bond is least and the badge of color relatively unimportant save as a badge; the real essence of this kinship is its social heritage of slavery, the discrimination and insult. . . . It is this unity which draws me to Africa. (258) By this point Du Bois was evidently conscious of and eager to reconcile the contradictions which inhered in his earlier racialist formulation of ethnic identity, one which obviously threatened to play right into the hands of the scientific racists who had gained ascendancy in the nineteenth century and whose arguments were predicated upon biologism. On African American Aesthetics / Critical Theory: “Criteria of Negro Art” (1926) Here, Du Bois’s concern is with the question of African American literary history. His point is that many African Americans at this stage (1926) of the struggle for equal rights are not too interested in aesthetic questions. After all, he cites others, “what have we who are slaves and black to do with Art” (752). For Du Bois, however, aesthetic questions are “part of the great fight we are carrying on” (752) and thus inseparable from socio-historical issues. Arguing that the pursuit of artistic beauty has everything to do with “Truth and Goodness – with the facts of the world and the right actions of men” (754), Du Bois imagines that “somehow, somewhere eternal and perfect Beauty sits above Truth and Right . . . but here and now and in the world in which I work they are for me unseparated and inseparable” (754). Du Bois asks: “Who shall let this world be beautiful? Who shall restore to men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep?” (754). His answer: We black folk may help for we have within us as a race new stirrings of the beginning of a new appreciation of joy, of a new desire to create, of a new will to be; as though in this morning of group life we are awakened from some sleep that at once dimly mourns the past and dreams a splendid future. (754) This realisation is brought home to us, he writes, particularly when as artists we face our own past as a people. . . . A realisation of that past, of which for long years we have been ashamed, for which we have apologised We thought nothing could come out of that past which we wanted to remember; which we wanted to hand down to our children. Suddenly this same past is taking on form, color and reality; and in a half shamefaced way we are beginning to be proud of it. (754) People of African descent, he argues, are beginning to realise the importance of formulating an artistic tradition, what the Romantic theorist Schlegel would describe as a ‘national tradition and national recollections.’ In the history of African and diasporic peoples, he argues, there is ample material for both tragedy and Romance better than those written by the Greeks and others. Arguing that “all Art is propaganda and ever must be” (755), Du Bois contends that “it is the bounden duty of black America to begin this great work of the creation of Beauty” (757), using the tools of “Truth” (757) and “Goodness” (757) to the point where the “apostle of Beauty thus becomes the apostle of Truth and Right” (757).