Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective

advertisement

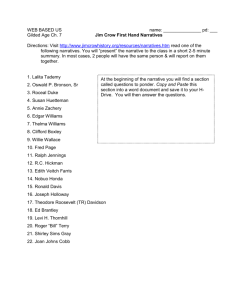

Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective Jennifer Trost Utica College, Utica, New York F O R MANY SEMESTERS, I taught an introductory class titled "The Global Perspective: The World Since World War H." In my world studies classes, I found a successful approach for teaching first-year and non-major students to enjoy reading about the world and to appreciate a global perspective. I chose a source-based approach and I used intemational personal or travel narratives for the majority of the reading. Students are attracted to the personal information rather than a synthesis, and the narration rather than analysis. They are drawn to specific examples of other cultures to which they can relate and they are very curious about the everyday lives of other people in the world. Problems in teaching a one-semester world history class include dealing with the dominance of Western culture, decisions about coverage, and student disinterest in the world. Overcoming the deeply rooted Euro-centric understanding of the world that dominates thinking in American higher education is difficult. Clearly, this view is changing, but it manifests itself in countless fundamental ways such as the terms "Third World," "The New World," "The East," and in the kinds of maps students are used to looking at which center on the prime meridian or have north in the upper half of the world.' This shift away from a national or Western focus has raised important pedagogical questions about how best to help students achieve a truly global perspective.-^ Another problem is the great deal of information to cover and the choices about what to leave out. In approaching the The History Teacher Volume 42 Number 2 February 2009 © Soeiety for History Education 178 Jennifer Trost problem of coverage, others have chosen to use an analytical focus. Peter Steams stresses change versus continuity across civilizations. Others use thematic issues such as the rise and fall of great powers, technology, or long-distance trade across countries.^ These analytical courses tend to emphasize theoretical issues and therefore often generalize about experiences. They do offer coherence and conceptual clarity that help students make sense of too much information. Some historians have argued for concentrating on the uniqueness of civilizations, the interaction between them, and the impact of the past on the present.'' These classes show students the relevance of history by connecting developments of the past or other cultures to the everyday aspects of their own lives. Finally, although one of the effects of the destruction of the World Trade Center Towers on September 11,2001 has been increased recognition that no nation is isolated, lower division students in the United States are still often uninterested in the world or do not know how to start learning about other cultures. It is difficult to get them to "see" their Westem identity. American students' knowledge of the world is often sketchy at best and, as a result, many other cultural practices appear only strange to them. The "Global Perspective" course is part of the general education curriculum and every entering student is required to take it. Many schools have moved toward including survey classes about world developments as part of students' general education. The "Global Perspective" course combines the disciplines of history, economics, and political science to study the non-Westem world. The course covers the post-colonial emergence of developing nations, the rise of intemational political and economic institutions, technological changes, and globalization. This thematic emphasis challenges many assumptions about national identity that students bring with them to college.^ Even though the time period is lirnited to the second half of the twentieth century and the focus is on some big themes, there is still the issue of which countries or cultures to study and how. My "Global Perspective" class has a loose historical structure and is generally chronological. I begin with background infonnation from the textbook about nineteenth-century industrialization, colonialism, and nationalism. I remind the students of these foundations often as we read the personal narratives since the narratives address the late twentieth-century undoing or evolution of these issues in the form of globalization and the spread of industrial economies, post-colonial politics, and independence or identity movements. Next, I set up the Cold War as the historical backdrop for much of the time span covered by the class. We spend the rest of the semester reading the personal narratives and the structure of the course becomes less chronological as we move from region to region. Using Personal Narratives to Teaeh a Global Perspective 179 This part of the course uses the personal narratives to make comparisons and explore themes such as community versus individualism, agricultural versus urban life, and different forms of government. I end the course with discussions of the current global economy, its effects on the students, and their place in the world. In teaching modem world history survey classes, I have found that in order to keep beginning-level students engaged in such challenges to their fundamental beliefs, it is crucial for the reading to be as accessible as possible. I have found, as have other history teachers, that using only general textbooks can be a disservice to these kinds of classes because students quickly lose interest and because textbooks can be monolithic* Books of primary documents rarely have the selection of issues or regions that I am interested in or find feasible to teach. Photocopied course packs are expensive and require attention to copyright laws. Using international personal narratives in my world history classes offers students in-depth first-person accounts of life in other cultures.^ Personal narratives are autobiographical accounts of living and/or traveling in specific countries or cultures. Some of the personal narratives I have used in class are written by visitors to foreign countries, and I call these travel accounts. Some personal narratives are written by observers of their own culture, sometimes after they have left home. As students read these accounts, they follow along with the writers' experiences as they cope with crossing cultural boundaries. These narratives are accessible versions of cross-cultural exchange theory, a thematic approach to world history pioneered by Jeremy Bentley and others.* By personalizing world history, I have students internalize other kinds of lives first and then fit those stories into the global pattem or concept I am trying to show them. By moving them temporarily outside of their own view, I can then ask them to think critically about how other lives may be different or similar to theirs. Since the class is primarily about developing critical thinking skills, the sacrifice of breadth for depth is not as great as it may seem. If students can successfully master analysis of one person's view, they can also understand other views. I have chosen to leverage an amount of coverage for connection and synthesis for sympathy. Student evaluations of the readings reveal that they are drawn to storytelling and that they can be inspired by someone else's life. My students see themselves in these narratives.' They see how other people their own age go to school, or do not go to school as the case may be. And by the time they are done with the semester, they understand why other young people in the world cannot go to school. Tliey see what other cultures consider to be a trip to the dentist: a swish of motorcycle gasoline or a scmb with a stick in some countries. Students are fascinated 180 Jennifer Trost by personal hygiene hahits in other countries. They see how other cultures organize their families, how other cultures treat women and children. Students are surprised to find that political expression in some countries can he a matter of life and death. They see how other cultures emphasize communalism and downplay individualism for the sake of harmony or physical survival. For instance, in Confucius Lives Next Door hy T. R. Reid, students read ahout Japanese social stability that comes from a tradition which reinforces group identity and are shocked, and a little skeptical, at the country's lack of crime. They realize just how much they take the existence of everyday crime for granted when they read ahout people with a high standard of living who do not live with the fear of crime. These hooks are successful for several reasons. Students come to understand on hoth a personal and intellectual level that America and the West are often not like the rest of the world. They come away with a real sense of their privilege and how their privilege rests on others' deprivation. They hegin to appreciate how consumer-oriented their lives are. Students also see that on a day-to-day basis, they actually do have much in common with people from other parts of the world. They read ahout other people who experience love, question the government, get drunk, fight for justice, and face the same kind of courtship anxieties they do. They can see advantages in the ways that some other countries handle their daily lives. For instance, in a past semester, in Songs to an African Sunset: A Zimbabwean Story by Sekai Nzenza-Shand, we read about the use of "èopo/o." Bopoto is the practice of women using puhlic space to verhally air their grievances, or "making a lot of angry noises." My students began to imagine what would happen at our school if one of them decided to try it, and they laughed and smiled. But they also understood that bopoto is an aspect of the justice system in a personal, non-writinghased, loosely structured culture. They could see its efficiency compared to the legal system in the United States. Students always have questions about what they read. They ask why the families they read ahout have so many children. And they also understand why the families they read about have so many children, because they have a Peace Corps volunteer asking the same question of a man in the former Zaire. They understand that large families equal old age insurance in countries without nursing homes and high infant mortality. They understand that they are more alone and on their own in America than many of the other people they read ahout who come from tightly knit, if poor, communities. By asking questions ahout the lives of people who produce the goods they huy, students come to see that owning a diamond, eating a chocolate har, drinking coffee, driving an SUV, or wearing certain clothes, the stuff of their own everyday life, intimately links them to the Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective 181 politics and economics of the world. The Ponds of Kalambayi by Mike Tidwell describes the dangerous and hardscrabble existence of African men who mine for diamonds. We discuss how many of these men have few economic choices which force them into diamond mining and compare that to the ease of Westerners buying expensive luxury goods. Having found a successful approach to teaching world history, I now regularly scour bookstores, catalogs, publishers' websites, and ask colleagues who teach in non-Westem fields for good personal narratives. Some books 1 have used include Son of the Revolution, a Chinese expatriate's memories of the Cultural Revolution and its effects on family life and individuals; A Month anda Day, a Nigerian man's diary about fighting foreign exploitation and indigenous corruption; The Ponds of Kalambayi, a Peace Corps volunteer's tribute to his time in the former Zaire and the effects of colonialism and poverty; Children of Cain, which explores the causes and personal effects of political violence in Latin America; and Guests of the Sheik, which details an American woman's assimilation into Iraqi village life in the 1950s. Lonely Planet Publications, the travel guide publisher, and the website Words Without Borders have some excellent titles.'« I have four criteria for choosing personal narratives, two are primarily for the student's satisfaction and two are for mine. First, the narratives must be primarily about everyday life and non-elites rather than "great" people. For instance, students were less attracted to the Ken Saro-Wiwa prison memoir A Month and a Day than they were to The Ponds of Kalambayi, a Peace Corps volunteer account, because they could more closely identify with the author and could envision themselves in a position of service to a community rather than risking their lives fighting for national autonomy against a multi-national company. Second, the personal narratives must be highly readable. This includes a manageable book length (about 200-250 pages works best) and predominately conversational writing style. While Jamaica Kincaid's book A Small Place is quite short (81 pages), it is the one book that absolutely everyone in my class read. We discussed the places they had visited as tourists, which led to discussions about being an outsider, the effects of colonialism, and the power of language. Third, the readings must shed light on some of the global issues that I am trying to teach students. I use books that illustrate economic interdependence, effects of imperialism or post-colonialism, and cross-cultural interactions. The book Beyond the Sky and the Earth is a very clear story about a Canadian woman's difficult and emotional journey into the culture and life of Bhutan. The author comes to question her consumer-oriented, clock-based life as she encounters a subsistence and seasonal economy. Fourth, the readings must have concrete information about the history, political and 182 Jennifer Trost economic system, religious beliefs, and culture of the country. I do not use travel narratives that are only impressionistic or are mostly about the author working through some personal emotional issues. Rather, I use narratives which emphasize the intellectual challenges of cross cultural journeys or ties of economic interdependence that would be of interest to students. For instance, Joe Kane in Savages explores the impact of oil pipelines on the life of the Huaorani in Ecuador which allows my students to discuss how their daily choices to drive cars tie them to oil-producing countries and people. Along with my goal of using personal stories to play to the curiosity of students, I also want to introduce students to the broad range of other primary sources. Novels also serve the same purpose of offering students a global perspective in a narrative format. I have used The Ugly American, The Mystic Masseur, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, and Things Fall Apart. The semester I used The Ugly American, a story about American involvement in the Vietnam War, it just so happened that a newspaper article quoting then-Representative Tom DeLay appeared in which he explained how he tried to intimidate the Chinese ambassador by standing tall and close and tightly squeezing the ambassador's hand because, as DeLay said, "that's the way I see these people."" My students recognized the parallels between the characters in the novel and the real life ugly American when they read about him. Recently, I have used the Spy Who Came in From the Cold and students could see the parallels between the tension of the Cold War and the current fears of terrorism. The main character of the novel, the spy Alec Leamus, does not know whom to trust, constantly lives with physical risk, and is alienated from normal ties to family and community. The Mystic Masseur and Things Fall Apart are post-colonial novels that explore the effects of imperialism on national identity, cultural practices, and economic development. In addition to reading personal narratives and novels, one other technique for engaging students in interactive learning about the world includes using Apple iBooks in class to read world newspapers. I have tried to solve some of the problems of apathy and disconnection of students toward the world by bringing them immediacy of issues. Now that many campuses are wireless, networked campus, iBooks are easy to use in class because there is no complexity, no wires. Students just come in and set them up. Reading world news in class introduces students to a new resource (international coverage of events) in a way with which they are thoroughly comfortable, on the Internet. I believe classes are best when they make use of primary documents. It is even better when students have their own primary documents. Students have their own laptop, can read at their own pace, and each has an individual connection to the world. Reading the Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective 183 news in class allows me to guide them in discussions about how they can apply what they have leamed in class to what is going on in the world. One semester, just after we finished reading Songs to an Afriean Sunset: A Zimbabwean Story, Zimbabwe had its national elections. We followed the unfolding drama and discussed why the country had a three-day voting period (very rural and isolated) and what some of the issues were (post-colonialism and race relations). Another example of students applying what they read in class to current events was the release of more of President Richard Nixon's tapes. One student brought in a clipping about the discussions between Nixon and Henry Kissinger regarding the use of nuclear bombs during American involvement in the Vietnam War. We had just finished reading Truong Nhu Tang's A Viet Cong Memoir: An Inside Aeeount of the Vietnam War and its Aftermath in which the Vietnamese author expressed concern about whether the Americans would use nuclear weapons. In the course evaluations, students mentioned they were quite impressed with the relevance of their readings. I tie together the use of narratives, novels, and news in class with writing assignments that foster critical thinking skills about the world. My paper topics ask students to imagine a conversation between two of the authors of the personal narratives as they each explain their culture to the other. 1 ask students to compare the way different narratives portray such concepts as individualism, family structure, religion, or the nature of violence. They move from the specific to the general, from the local to the global, by using personal narratives to learn about the world. Classroom resources that personally connect students to world issues help students make sense of cultural diversity. Rather than using books which try for the impossible, for coverage, students are well served by smaller, more intense readings. Since one of the goals of a liberal arts education is to prepare students for the world they will face, students need to know how to discuss other cultures. They need to be able to identify with other values and world-views since they live in a world of competing ideologies, of which theirs is only one. A single textbook will not give my students an understanding of diverse voices, but intemational personal narratives will. Notes 2. For a South Up map, go to <www.odt.org Michael Geyer and Charles Bright, "World History in a Global Age,'' American 184 Jennifer Trost Historical Review 100 (October 1995): 1034-1060; Joan Arno, "The NEH Collaborative Seminar and the Dilemmas of Teaching World History," The History Teacher 29 (November 1995): 93-100; William H. McNeill, "Colleges Must Revitalize the Teaching and Study of World History," The Chronicle of Higher Education 36 (8 August 1990): A36. 3. Steve Gosch, "Cross-Cultural Trade as a Framework for Teaching World History: Concepts and Applications," The History Teacher 27 (August 1994): 425-431. 4. Samuel A. Oppenheim, "World History in Theory and Practice: An Essay," The History Teacher 29 (May 1996): 315-321. 5. Peter N. Steams, "Student Identities and World History Teaching," The History Teacher 33 (February 2000): 185-192. 6. Paul Otto, "History as a Humanity: Reading and Literacy in the History Classroom," The History Teacher 26 (November 1992): 51-60. 7. In this regard, my approach draws on the strengths of social history which emphasizes the experiences of non-elites, everyday life, and themes of family, sexuality, work, and resistance. 8. Jerry H. Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Stephen S. Gosch, "Cross-Cultural Trade as a Framework for Teaching World History: Concepts and Applications," The History Teacher 21 (August 1994): 425-431. 9. Cognitive psychologists know that learning happens best when instructors help students make connections to what they already know, connections to their own lives, and relate new material to their own experiences. C. S. Symons and B. T. Johnson, "The SelfReference Effect in Memory: A Meta-Analysis," Psychology Bulletin 121, no. 3 ( 1997): 371-394. 10. For fiction and non-fiction in translation, go to "Words Without Borders" at <www.wordswithoutborders.org>. 11. "A Lesson in Diplomacy," Washington Post National Weekly Edition, 24 April 2000, 22. Appendix 1: Class Readings Personal Narratives Ash, Timothy Garton. The File: A Personal History. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. British academic returns to Germany after the Cold War to view his Stasi file and meet those who spied on him. Explores political repression and effects on personal relationships during Cold War. Femea, Elizabeth Wamock. Guests of the Sheik: An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village. New York: Anchor Books, 1989 (originally 1965). American anthropologist enters Iraqi society by befriending local women. Learns about a culture that is family, community, and religiously ordered. Heng, Liang and Judith Shapiro. Son of the Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1984. Chinese expatriate writes about the effects of ideology on family life and individual identity. Describes experiences of the Cultural Revolution and power of ideology. Kane, Joe. Savages. New York: Penguin, 1996. American writer travels in the Ecuadorian Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective 185 Amazon jungle with native tribes to document effects of multi-national oil company policies. Shows the effects of wage labor and Christian missionaries on family ties and subsistence economies. Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York: Vintage, 1997 (originally 1988). Antiguan writer explores efFects of British imperialism and foreign tourism on her country. Very powerful voice for developing nations. Nzeski-Shand, Sekai. Songs to an African Sunset: A Zimbabwean Story. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet Publications, 1997. Expatriate Zimbabwean woman returns home to bury her brother who died of AIDS. Reflects on transition between old traditions and modernity and cultural conflict between African and Western culture. Reid, T. R. Confucius Lives Next Door: What Living in the East Teaches Us About Living in the West. New York: Vintage Books, 2000. American journalist shows how Japanese society values communalism and harmony rather than individual expression. Explores ways that Japanese have adopted American popular culture. Rosenberg, Tina. Children of Cain: Violence and The Violent in Latin America. New York: Penguin, 1991. American journalist interviews torturers and the tortured to understand political violence and how violence becomes normal. Examines effects of political culture on rule of law versus rule by power. Saro-Wiwa, Ken. A Month and A Day: A Detention Diary. New York: Penguin, 1995. Nigerian activist applies Western principles of independence and freedom to struggle for economic autonomy and political reform. Argues for social justice while imprisoned for criticizing the military government. Tidwell, Mike. The Ponds of Kalambayi: An African Sojourn. New York: Lyons and Burford, 1990. American Peace Corps volunteer spends two years in former Zaire and questions his notions of privacy, wealth, and individualism. Truong, Nhu Tang. A Vietcong Memoir: An Insider Account of the Vietnam War and its Aftermath. New York: Vintage Books, 1986. Exiled Vietcong Minister of Justice explains Vietnam War as a nationalist independent movement. Shows personal sacrifices of those fighting for social justice and an ideology. Zeppa, Jaime. Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan. New York: Riverhead Books, 1999. Canadian student moves to Bhutan to teach for two years, but ends up marrying a Bhutanese and rejecting Western materialism and converting to Buddhism. Novels Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. New York: Anchor Books, 1994 (originally 1959). Nigerian author shows what happens to tribal society when outsiders overwhelm it. Post-colonial critique of imperialism. Le Carre, John. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. New York: Ballantine Books, 1992 (originally 1963). British author illustrates the ends that governments use to achieve national security goals and the personal costs to those involved. Creates a mood of confusion and fear. Lederer, William J. and Eugene Burdick. The Ugly American. New York: W.W.Norton, 1999 (originally 1958). American authors satirize American policies in Vietnam. Places Vietnam War in global context and makes fun of Western arrogance. Naipaul, V. S. The Mystic Masseur New York: Vintage Books, 2002 (originally 1957). Trinidadian author follows failed schoolteacher as he searches for greatness. Parable about Trinidadian search for identity after the end of British imperialism. 186 Jennifer Trost Appendix II: Class Syllabus The Global Perspective: The World Since World War II Instructor; Dr. Jennifer Trost This course will survey various global issues arising since the end of World War II. The course combines the disciplines of history, political science, and economics. Emphasis will be placed on the interaction of the superpowers during the Cold War, the post-colonial emergence of the "Third World," the ascendancy of regional and international economic and political institutions, technological innovation as a global blessing and burden, and the reshaping of contemporary Europe. We will focus on the regions of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and the Caribbean. We will use memoirs, music, autobiographies, maps, documentaries, and films to help understand global changes since 1945 and the effects they had on everyday life and ordinary people. By reading about developments in other societies, we come to understand our own even better. This course will consist of discussion based on the assigned readings and lectures. When you have finished this course, you should be able to ask historically-minded questions, think about current issues in terms of historical arguments, write concise, analytical essays, and speak cogently about what you think. No pre-requisites, 3 credits. Course Requirements and Grading * Graded assignments include two Papers (about 1000 words, 4 pages), short writing assignments, quizzes, and a Final Exam. 15% 30% 15% 10% 15% 15% Human Development Report Analysis ( 10% written, 5% presentation) 2 Papers Class Participation 10 Current Events Gists 15 Reading Quizzes Final Exam Explanation of United Nations Human Development Report Analysis: For this paper (500 words, 2 pages), you need to make two arguments based on evidence in your section of the report; You will then present one of those conclusions to the class and briefly (5 minutes) explain your section of the report. Explanation of Reading Quizzes: These quizzes consist of simple questions about the material to give you credit for having done the reading for the day. They will be given about once a week. They are pass/fail. Explanation of Papers: These are analytical papers of about 1000 words (4 pages) which make use of books we read in class. The paper grade includes a first draft and final draft. See the topics at the end of the syllabus. Explanation of Current Events Gists: This semester while we are studying the history and politics of the world, I would like you to be aware of current world events. You will see Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective 187 that events in the past are relevant to today. This semester, the New York Times will be delivered every weekday to campus. Please bring a copy of the New York Times to class with you every day. For your current events gists (due on Fridays), you need to explain in about 5 sentences what you think was the most important global event of the week, why you think it was important, and how the New York Times described the event. You need to give the source and date of the infonnation. On Fridays, we will spend class time discussing world issues covered in the New York Times. Course Materials Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart Truong Nhu Tang, A Viet Cong Memoir: An Inside Account of the Vietnam War and its Aftermath Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place Gelareh Asayesh, Saffron Sky: A Life Between Iran and America William J. Duiker, Twentieth -Century World History, 2nd. ed. Daily Class Schedule Some Background: Industrialization Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, c\\. I Some Background: Imperialism Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 2 Some Background: Nationalism Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 5 The Coming Cold War and the Emergence of the "Third World" Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 7 Communism and the Cold War Reading and Gist: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 8 How Do Countries Compare? What does "Human Development" Mean? United Nations Human Devetopment Report 2004 Analysis Due Presentations Africa and Economic Development Reading and Gist: Twentieth-Century World History, c\i. 14 Tribal Life in Nigeria, Africa Reading: Things Fall Apart, ch. \-6 Family and Food in Africa Reading: Things Fall Apart, ch. 7-10 1 gg Jennifer Trost White Europeans and Black Africans Reading and Gist: Things Fall Apart, ch. 11-17 Imperialism and its Effect on Africa Reading: Things Fall Apart, ch. 18-25 Asian Nationalism Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 13 Becoming a Vietnamese Revolutionary Reading and Gist: A Vietcong Memoir, ch. 1-6 Vietnam: East vs. West Reading: A Vietcong Memoir, ch 7-11 Fighting a War in Vietnam Reading:/! Vietcong Memoir, c\\ 12-15 The World During the Cold War and the End of the Vietnam War Reading and Gist: A Vietcong Memoir, ch 16-19 Aftermath of the War in Vietnam Reading: A Vietcong Memoir, ch. 20-24 Diamonds in Africa: First World/Third World Video: The Diamond Empire Images of the Cold War Video: The Cold War, pt. 1 Latin American Nationalism Reading and Gist: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 11 (242-249) Music ofthe Cold War Understanding Other Cultures Reading: Horace Miner, "Magical Practices among the Nacirema" The End of Empire, Post Colonial Asia Reading and Gist: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 12 Visiting The Caribbean as a Tourist Reading: A Small Place, pt 1 Real Life in Antigua Reading: A Small Place, pt 2 The Caribbean and Imperialism Reading and Gist: A Small Place, pt 3, 4 Using Personal Narratives to Teach a Global Perspective 189 Developments in the Middle East Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 15 Women in Modem Iran Movie: Leila Modernity vs. Tradition in Iran Movie: Leila Moving Between Cultures Reading: Saffron Sky, ch. I Growing Up in Iran Reading: Saffron Sky, ch. II-III Migrating and Adjusting to America Reading and Gist: Saffron Sky, ch. IV-V Iran After the Revolution Reading: Saffron Sky, ch. VI East vs. West Reading: Saffron Sky, ch. VII-X The Global Economy Reading: Twentieth-Century World History, ch. 17 Paper Topic #1 Imagine a conversation between Chinua Achebe and Truong Nhu Tang in which they explain Nigeria and Vietnam to each other. Write a paper in which Achebe explains Nigerian culture and history to Tang, and Tang explains Vietnamese culture to Achebe. In your paper, list two differences and two similarities between Nigeria and Vietnam as described by Achebe and Tang. Paper Topic #2 In your first paper, I asked you to make general comparisons about life in two different countries. Countries and their cultures are very complex. One way to simplify our discussion of cultures is to pick a single theme with which to compare them. In this paper, 1 would like you to use the theme of imperialism to compare cultures. Using the books from class, you need to compare the way Chinua Achebe or Truong Nhu Tang and Jamaica Kincaid explain the effects of imperialism on each of their countries. Be sure to note the similarities or differences between the effects on each country.