File

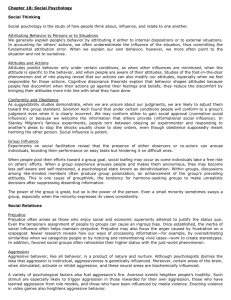

advertisement

Social Psychology Unit Review Terms to Review social psychology attribution theory fundamental attribution error attitude central route persuasion peripheral route persuasion foot-in-the-door phenomenon face-in-the-door phenomenon role cognitive dissonance theory conformity normative social influence informational social influence social facilitation social loafing deindividuation group polarization groupthink culture norm prejudice stereotype discrimination ingroup outgroup ingroup bias scapegoat theory just-world phenomenon aggression frustration-aggression principle mere exposure effect passionate love companionate love equity self-disclosure altruism bystander effect social exchange theory reciprocity norm social-responsibility norm conflict mirror-image perceptions self-fulfilling prophecy superordinate goals Review Questions 1) How do we tend to explain others’ behavior and our own? 2) Does what we think affect what we do, or does what we do affect what we think? 3) What do experiments on conformity and compliance reveal about the power of social influence? 4) How is our behavior affected by the presence of others or by being part of a group? 5) What are group polarization and groupthink? 6) How do cultural norms affect our behavior? 7) How much power do we have as individuals? Can a minority sway a majority? 8) What is prejudice? 9) What are the social and emotional roots of prejudice? 10) What are the cognitive roots of prejudice? 11) What biological factors make us more prone to hurt one another? 12) What psychological factors may trigger aggressive behavior? 13) Why do we befriend or fall in love with some people but not with others? 14) How does romantic love typically change as time passes? 15) When are we most—and least—likely to help? 16) How do social traps and mirror-image perceptions fuel social conflict? 17) How can we transform feelings of prejudice, aggression, and conflict into attitudes that promote peace? Review Questions with Answers 1) How do we tend to explain others’ behavior and our own? We generally explain people’s behavior by attributing it to internal dispositions and/or to external situations. In committing the fundamental attribution error, we underestimate the influence of the situation on others’ actions. When explaining our own behavior, we more often point to the situation. Our attributions influence our personal, legal, political, and workplace judgments. 2) Does what we think affect what we do, or does what we do affect what we think? Attitudes influence behavior when other influences are minimal, and when the attitude is stable, specific to the behavior, and easily recalled. Studies of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon and of role-playing reveal that our actions (especially those we feel responsible for) can also modify our attitudes. Cognitive dissonance theory proposes that behavior shapes attitudes because we feel discomfort when our actions and attitudes differ. We reduce the discomfort by bringing our attitudes more into line with what we have done. 3) What do experiments on conformity and compliance reveal about the power of social influence? Asch’s conformity studies demonstrated that under certain conditions people will conform to a group’s judgment even when it is clearly incorrect. We may conform either to gain social approval (normative social influence) or because we welcome the information that others provide (informational social influence). In Milgram’s famous experiments, people torn between obeying an experimenter and responding to another’s pleas to stop the apparent shocks usually chose to obey orders. People most often obeyed when the person giving orders was nearby and was perceived as a legitimate authority figure; when the person giving orders was supported by a prestigious institution; when the victim was depersonalized or at a distance; and when no other person modeled defiance by disobeying. 4) How is our behavior affected by the presence of others or by being part of a group? Social facilitation experiments reveal that the presence of either observers or co-actors can arouse individuals, boosting their performance on easy tasks but hindering it on difficult ones. When people pool their efforts toward a group goal, social loafing may occur as individuals free ride on others’ efforts. Deindividuation—becoming less self-aware and self-restrained—may happen when people are both aroused and made to feel anonymous. 5) What are group polarization and groupthink? Discussions among like-minded members often produce group polarization, as prevailing attitudes are intensified. This is one cause of groupthink, the tendency to suppress unwelcome information and make unrealistic decisions for the sake of group harmony. To prevent groupthink, leaders can welcome a variety of opinions, invite experts’ critiques, and assign people to identify possible problems in developing plans. 6) How do cultural norms affect our behavior? Cultural norms are rules for accepted and expected behaviors, ideas, attitudes, and values. Across places and over time cultures differ in their norms. Humans share a capacity for culture, and that shared capacity enables our striking human diversity by influencing our everyday attitudes and behaviors. 7) How much power do we have as individuals? Can a minority sway a majority? The power of the group is great, but even a small minority may sway group opinion, especially when the minority expresses its views consistently. 8) What is prejudice? Prejudice is a mixture of beliefs (often stereotypes), negative emotions, and predispositions to action. Prejudice may be overt (such as openly and consciously denying a particular ethnic group the right to vote) or subtle (such as feeling fearful when alone in an elevator with a stranger from a different racial or ethnic group). 9) What are the social and emotional roots of prejudice? Social and economic inequalities may trigger prejudice as people in power attempt to justify the status quo or develop an ingroup bias. Fear and anger feed prejudice, and, when frustrated, we may focus our anger on a scapegoat. 10) What are the cognitive roots of prejudice? In processing information, we tend to recognize diversity in our own groups but to overestimate similarities in other groups, as in the other-race effect. We also notice and remember vivid cases. These trends help create stereotypes. Favored social groups often rationalize their higher status with the just-world phenomenon. 11) What biological factors make us more prone to hurt one another? Aggression is a complex behavior that results from an interaction between biology and experience. For example, genes influence our temperament, making us more or less likely to respond aggressively when frustrated in specific situations. Experiments stimulating portions of the brain (such as the amygdala and frontal lobes) have revealed neural systems in the brain that facilitate or inhibit aggression. Biochemical influences, such as testosterone and other hormones; alcohol (which disinhibits); and other substances also contribute to aggression. 12) What psychological factors may trigger aggressive behavior? Frustration and other aversive events (such as heat, crowding, and provocation) can evoke hostility, especially in those rewarded for aggression, those who have learned aggression from role models, and those who have been influenced by media violence. Enacting violence in video games or viewing it in the media can desensitize people to cruelty and prime them to behave aggressively when provoked, or to view sexual aggression as more acceptable. 13) Why do we befriend or fall in love with some people but not with others? Three factors are known to affect our liking for one another. Proximity— geographical nearness—is conducive to attraction, partly because mere exposure to novel stimuli enhances liking. Physical attractiveness increases social opportunities and influences the way we are perceived. As acquaintanceship moves toward friendship, similarity of attitudes and interests greatly increases liking. 14) How does romantic love typically change as time passes? Passionate love is an aroused state that we cognitively label as love. The strong affection of companionate love, which often emerges as passionate love subsides, is enhanced by an equitable relationship and by intimate selfdisclosure. 15) When are we most—and least—likely to help? Altruism is unselfish regard for the well-being of others. We are less likely to help if others are present. This bystander effect is especially apparent in situations where the presence of others inhibits our noticing the event, interpreting it as an emergency, or assuming responsibility for offering help. Explanations of our willingness to help others focus on social exchange theory (the costs and benefits of helping); the intrinsic rewards of helping others; the reciprocity norm (we help those who help us); and the socialresponsibility norm (we help those who need our help). 16) How do social traps and mirror-image perceptions fuel social conflict? Social conflicts are situations in which people perceive their actions, goals, or ideas to be incompatible. In social traps, two or more individuals engage in mutually destructive behavior by rationally pursuing their own self-interests. People in conflict tend to expect the worst of each other, producing mirrorimage perceptions that can become self-fulfilling prophecies. 17) How can we transform feelings of prejudice, aggression, and conflict into attitudes that promote peace? Enemies sometimes become friends, especially when the circumstances favor equal-status contact, cooperation to achieve superordinate goals, understanding through communication, and reciprocated conciliatory gestures.