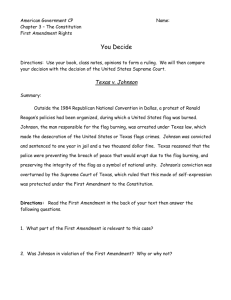

Implementing a Flag-Desecration Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

advertisement