February/March 2015 - El Paso Bar Association

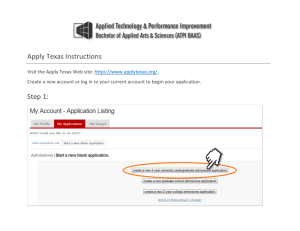

advertisement