Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050

advertisement

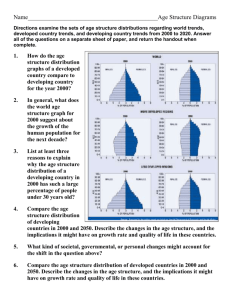

Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 A special report from The Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Contents Overview2 Top ten economies in 2050 at market exchange rates 3 The rise of Asia continues 4 Global dominance of the top three economies 5 A new era of global demographic decline 6 Population growth will still benefit a few 7 For most, population as a source of growth will need to be replaced 9 Collectively rich, individually not so rich 11 Long-term methodology 12 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 1 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Overview W ith many companies making strategic business decisions over long time frames, the long-term projections of The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) provide information to facilitate such decisions. Long-term forecasts and scenarios are also key to understanding some of the big economic issues that will shape global business in the coming decades. The EIU has an established methodology for producing long-term economic forecasts for 82 economies. We have recently completed an extension of our forecast horizon to 2050, and below we consider some of the key trends that are highlighted by these extended forecasts. 2 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Top ten economies in 2050 at market exchange rates Nominal GDP (US$ bn) 2014 US [1] 2050 17,419 China [2] 10,335 Japan [3] 4,606 Germany [4] 3,865 China [1] 105,916 70,913 US [2] India [3] Indonesia [4] 63,842 15,432 UK [5] 2,951 Japan [5] 11,367 France [6] 2,835 Germany [6] 11,334 Brazil [7] 2,346 Brazil [7] Italy [8] 2,149 Mexico [8] 9,826 India [9] 2,055 UK [9] 9,812 Russia [10] 1,861 France [10] 9,671 10,334 Economy moves up rankings Economy moves down rankings Economy remains at rankings Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. C hina is expected to overtake the United States in 2026 in nominal GDP in US dollar terms and maintain its position as the largest economy to 2050. India is expected to move up the rankings to third place, with real growth averaging close to 5% up to 2050. Indonesia and Mexico are expected to leap into the top ten world economies from 16th and 15th place in 2014 to fourth and ninth place respectively by 2050. We do not expect the representation of Western economies within the top-ten listing to become insignificant. The United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and France will all move down the rankings, but only Italy will lose its place within the top ten. © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 3 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 The rise of Asia continues Regional share of global GDP (%) Asia-Pacific Americas Europe 100 Middle East & Africa 100 90 90 80 80 70 70 60 60 50 50 40 40 30 30 20 20 10 10 0 0 1981-90 1991-2000 2001-10 2011-18 2019-30 2031-40 2041-50 Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. T he rise of Asia is not a new phenomenon; the rise of Japan and South Korea has been witnessed over the second half of the 20th century. The start of the new millennium saw another boom, with many Asian economies recording high growth rates that took their share of global GDP from 26% to 32% between 2000 and 2014. Our extended long-term forecasts suggest that Asia’s rise will continue up to 2050—not quite at the same pace, but by 2050 it will account for 53% of global GDP. 4 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Global dominance of the top three economies Nominal GDP, 2050 (US$ trn) 120 120 100 100 105.92 80 80 70.91 60 60 63.84 52.67 40 40 20 20 0 0 China US India Next 5 economies Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. B y 2030 the top three economies of the world will be the US, China and India. Such will be the growth of the two latter countries, in particular, that by 2050 they will each be richer than the next five (Indonesia, Germany, Japan, Brazil, and the UK) put together. This will represent a scale of wealth relative to the rest of the top ten that is unique in recorded history. Given China’s and India’s economic might, they will take on a much bigger role in addressing global issues such as climate change, international security and global economic governance. In the medium term, this will require the world’s existing powers—notably the US—to let India, and especially China, play a greater role on the world stage and adapt international institutions to allow them to exert greater influence. © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 5 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 A new era of global demographic decline Real GDP (% change - CAGR) 4.5 Middle East & Africa Asia-Pacific Americas Europe World 4.5 4.0 4.0 3.5 3.5 3.0 3.0 2.5 2.5 2.0 2.0 1.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5 0.0 0.0 2011-19 2020-30 2031-40 2041-50 Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. G lobal growth to 2050 is not expected to decline dramatically from its average historical levels. However, regional growth rates are expected to begin to decline across every region after 2030. Average growth in global population (%) 2.0 Population Working-age population 2.0 1.8 1.8 1.6 1.6 1.4 1.4 1.2 1.2 1.0 1.0 0.8 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.0 0.0 1991-2000 2001-10 2011-18 2019-30 2031-40 2041-50 Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. Much of the global growth in recent decades has been driven by population growth. Long-term population estimates, however, reveal that growth in the global population is expected to see a dramatic decline from an average of 1.3% in the 1980-2014 period to 0.5% across the 2015-50 period. The slowdown in the growth rate of the global working-age population will be even starker, with a drop to 0.3% in the 2015-50 period, compared with an average growth rate of 1.7% in the 1980-2014 period. 6 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Population growth will still benefit a few T he majority of countries in Africa and the Middle Eastern region will benefit from an increase in their working populations, which will be an advantage in sustaining higher growth rates in the forecast period. The potential labour forces of Angola, Nigeria and Kenya are expected to almost triple between 2014 and 2050, rising respectively from 9m to 28m, 56m to 161m and 18m to 48m. The labour forces of Algeria, Egypt and Iran are expected to increase considerably too, doubling in size by 2050. Largest increase in labour force (m) 2050 2014 180 180 160 160 140 140 120 120 100 100 80 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 0 Nigeria Pakistan Philippines Kenya Egypt Iran Angola Algeria Kuwait Libya Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. Contribution to real GDP growth, 2019-50 (% CAGR) of which Labour of which Capital and TFP Real GDP (% change) 6.0 6.0 5.0 5.0 4.0 4.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 Angola Kenya Nigeria Pakistan Philippines Venezuela Algeria Egypt Iran South Africa Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 7 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 These economies will primarily benefit from favourable demographics in the forecast period, with higher birth rates supporting a healthy supply of workers. To a lesser extent, some of these economies will also be able to benefit from increased participation rates, as growing numbers of women enter the labour force in some economies and retirement ages are raised in others to increase the labour supply and support growth. Policies pursued to increase participation rates, however, will not be able to boost growth significantly. Countries with favourable demographics will therefore have an advantage in terms of sustaining higher levels of growth. The contribution to growth from changes to the labour force for these economies will be positive and represent a larger driver of growth than capital and total factor productivity. For countries with favourable demographics, our forecasts assume that growth-friendly policies are pursued and are successful in providing jobs for a growing workforce and ensuring longer-term growth. Failure to achieve this will lead to a growing number of potential workers unable to find employment, resulting in a source of significant political instability and a missed opportunity in terms of seizing an advantage offered by favourable demographics. 8 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 For most, population as a source of growth will need to be replaced M ost of Europe and East Asia, by contrast, is expected to see labour-force declines, representing a severe drag on growth. Japan will see the greatest decline of over one-quarter, from 66m to 47m; China and South Korea are also expected to experience a 17-18% contraction in their labour forces. Within Europe, Greece, Portugal and Germany will see their available labour forces decline by over onefifth, falling between 2014 and 2050 from 4.8m to 3.8m, 5.2m to 4.2m and 45m to 35m respectively. As a group, emerging European economies (with a few exceptions, including Kazakhstan and Turkey) will experience persistent declines in their available labour forces, ranging between 20% and 30%. These economies will see the drop in their labour forces act as a drag on growth. Largest decrease in labour force (m) 2050 2014 70 70 60 60 50 50 40 40 30 30 20 20 10 10 0 0 Japan Germany Thailand South Korea Ukraine Taiwan Romania Portugal Greece Lithuania Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. Contribution to real GDP growth, 2019-50 (% CAGR) of which Labour of which Capital and TFP Real GDP (% change) 4.0 4.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 -1.0 -1.0 Japan Thailand Romania Germany Ukraine Taiwan Russia Greece Portugal South Korea Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 9 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Policies to boost participation rates will be pursued to soften the negative effects of unfavourable demographics, but these will not be sufficient. Immigration policies will move up high on government agendas as economies will be required to compete to attract a limited global pool of labour. A country’s ability to switch to different sources of growth will be crucial. For some countries which are starting from a low capital base, there will be the potential for investment to support growth. These countries will still be able to make gains by moving from less technologically intensive production to capital-intensive manufacturing production. For more advanced economies, however, it will be gains from the more efficient usage of capital through increased technological progress as a result of investment in research and development (R&D) that will boost growth. A low level of investment following the financial crises in many economies suggests that the outlook for such gains will be unspectacular. 10 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Collectively rich, individually not so rich E merging markets are expected to grow faster than developed economies, and as a result developing countries such as China and India are likely to overtake current global leaders such as the US, Japan and Western Europe, while other emerging markets, such as Indonesia and Mexico, will rank among the top ten economies at market exchanges rates by 2050, overtaking economies such as Italy and Russia. By contrast, in terms of income per capita, a measure of individual spending power, today’s advanced economies are likely to continue to dominate. Emerging economies such as China, India and Indonesia are projected to grow significantly in terms of per-capita income. China is expected to almost catch up with Japan by 2050, and India will see its spending power rise from representing 3% of the spending power of a US consumer to 24% by 2050. The comparable spending power of a Chinese consumer compared with that of a US consumer will increase from 14% in 2014 to just under 50% - a significant catch-up. The rise of emerging economies will continue to provide new customers and opportunities to scale up. However, despite their low growth outlook advanced economies cannot be ignored, as the spending power of consumers in these regions will remain significantly higher. Nominal GDP per capita (US$) 2000 2014 Japan 37,639 US US 36,449 Germany 23,744 Germany Mexico Brazil 6,580 3,788 47,688 Italy Brazil 11,570 Spain Mexico 10,426 Sri Lanka Indonesia 840 Indonesia 7,623 3,508 India 1,637 156,940 Germany 36,266 China 174,995 Sweden Japan China 943 India 482 54,634 2050 Hungary Russia South Africa 102,323 82,547 65,910 47,337 42,682 40,974 Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit. © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 11 Long-term macroeconomic forecasts Key trends to 2050 Long-term methodology T he methodology used to derive our long term-forecasts is distinct from that used to generate our five-year (medium-term) forecasts. Medium-term forecasts are based on a “demand-side” forecasting framework, which assumes that supply adjusts to meet demand either directly through changes in output or through the drawing-down (or building-up) of inventories. Such a framework is appropriate for constructing short- and medium-term projections, where output can deviate substantially (but temporarily) from its long-run sustainable level. But a demand-side framework is not appropriate for forecasting over the long term. Instead, we utilise a supply-side framework, in which output is determined by the availability of labour and capital equipment and the growth in productivity. The Economist Intelligence Unit is well placed to produce long-term projections and scenarios. We have considerable experience in tracking and forecasting a variety of economic and institutional factors, which our analysis suggests are closely related to long-term growth prospects. These factors include the availability of an educated workforce, the openness of the economy to trade, the quality of institutions (including the legal framework and the quality of the bureaucracy), fiscal policy, the degree of government regulation and movements in the population of working age relative to the overall population. In addition, the income gap between each country and the global technological leader (the US) is important, as this illustrates the potential for economic catch-up by importing ideas and techniques. Forecasts of GDP growth per capita based on these factors can then be combined with demographic projections (taken primarily from UN population projections) to give forecasts for overall GDP growth. 12 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2015 While every effort has been taken to verify the accuracy of this information, The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this report or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in this report. Cover image - © chungking/ Shutterstock.com LONDON 20 Cabot Square London E14 4QW United Kingdom Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 E-mail: london@eiu.com NEW YORK 750 Third Avenue 5th Floor New York, NY 10017 United States Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 E-mail: newyork@eiu.com HONG KONG 1301 Cityplaza Four 12 Taikoo Wan Road, Taikoo Shing Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: hongkong@eiu.com GENEVA Rue de l’Athénée 32 1206 Geneva Switzerland Tel: (41) 22 566 2470 Fax: (41) 22 346 93 47 E-mail: geneva@eiu.com