Lecture 15 - ECO100

advertisement

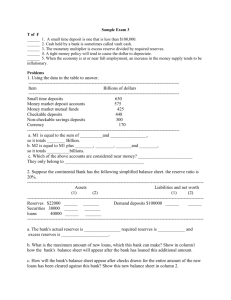

Prof. Gustavo Indart Department of Economics University of Toronto ECO 100Y INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS Lecture 15. MONEY, BANKING, AND PRICES 15.1 WHAT IS MONEY? 15.1.1 Classical and Modern Views For the Classical school, there exists a clear dichotomy between the real sector and the monetary sector of the economy. For this school, the allocation of resources and the determination of real national income depend exclusively on relative prices, and thus these are determined in the real sector of the economy and not in the monetary sector. In their view, an increase in the nominal supply of money leads to a proportional increase in all prices and to no change in relative prices. Therefore, an increase in the nominal supply of money will not affect the allocation of resources or the level of real national income. For that reason, money is said to be neutral in the determination of real national income (GDP). The modern view of money, on the other hand, accepts the neutrality of money in the long-run but not during the adjustment process. 2 15.1.2 The Definition of Money The definition of money depends on the function of money we are referring to. The most common definition, however, considers money as a medium of exchange. A medium of exchange is anything that is generally acceptable in exchange for goods and services. Without a medium of exchange, it would be necessary to exchange goods directly for other goods − an exchange known as barter. Barter is the direct exchange of goods for goods. Barter can take place only when there is a double coincidence of wants. A double coincidence of wants is a situation that occurs when person A wants to buy what person B is selling and person B wants to buy what person A is selling. 15.1.3 The Functions of Money Money has four functions. It serves as a: 1) medium of exchange; 2) unit of account; 3) standard of deferred payment; and 4) store of value. 1) Medium of Exchange Any commodity or asset that serves as a generally acceptable medium of exchange is money. Money makes unnecessary the double coincidence of wants. People with something to sell will always accept money in exchange for it, and people who want to buy will always offer money in exchange. 2) Unit of Account An agreed measure for stating the prices of goods and services is a unit of account. In this way, the opportunity cost of a commodity can easily be stated in terms of any other commodity. 3 Without money as a unit of account, the price of a commodity would have to be stated in terms of each and every commodity in the economy. 3) Standard of Deferred Payment An agreed measure that enables contracts to be written for future receipts and payments is called a standard of deferred payment. If you borrow money to finance your college education, your future commitment will be agreed to in dollars and cents. Money is used as the standard for a deferred payment. 4) Store of Value Any commodity that can be held and exchanged later for some other commodity or service is a store of value. Most physical objects are stores of value. Financial assets (e.g., bonds, treasury bills, etc.) are also stores of value. There are no stores of value that are completely safe and predictable. The value of any physical object, paper security, and even of money fluctuates overtime. The more stable and the more predictable the value of a commodity, the better can it act as a store of value. Thus the higher and the more unpredictable the inflation rate, the less useful is money as a store of value. It is essential that money be a store of value. Otherwise, it would not be accepted as a medium of exchange. 15.1.4 The Different Forms of Money Money can take four different forms: 1) commodity money; 2) convertible paper money; 3) fiat money; and 4) private debt money. 4 1) Commodity Money Commodity money is a physical commodity valued in its own right and also used as a medium of exchange. Many commodities have served as commodity money at different times and places. The most common commodity money has been coins made from metals such as gold, silver, and copper. The main advantage of commodity money is that the commodity is valued for its own sake and can be used in ways other than as a medium of exchange. This fact provides a guarantee of the value of the money. The main advantages of precious metals as commodity money were that their quality was easily verified, and that they were easily divisible into smaller units. The main disadvantages of precious metals as commodity money were that it was also easy to cheat on the value of the money through clipping and debasement. Clipping is reducing the size of coins by an imperceptible amount. Debasement is creating a coin with a lower-than-standard silver or gold content. 2) Convertible Paper Money A paper claim to a commodity that circulates as a medium of exchange is called convertible paper money. That is, convertible paper money is a promise to pay on demand a certain amount of gold. The first issuers of convertible paper money were goldsmiths, followed by banks. In particular, bank notes (banks' promises to pay) remained an important part of the money supply in Canada until 1950. When a country's money is convertible into gold, the country is said to be on a gold standard. 5 Once the convertible paper money system was operating, it became apparent that it was not necessary to keep an equal amount of commodity money to back the convertible paper money in circulation. As long as a sufficient deposit were kept, more convertible paper money was possible to be created and lent for a profit. This type of money is called fractionally backed paper money. 3) Fiat Money Fiat money is an intrinsically (almost) worthless commodity that serves the function of money. The term "fiat" means "by order of the authority". Examples of fiat money are the bank notes and coins we use in Canada today. People are willing to accept fiat money in exchange for the goods and services they sell only because they know it will be honoured when they go to buy goods and services. The replacement of commodity money by fiat money enables the commodities themselves to be used productively. 4) Private Debt Money Private debt money is a loan that the borrower promises to repay in currency on demand. By transferring the entitlement to be repaid from one person to another, such a loan can be used as money. The most important example of private debt money is chequing deposits at chartered banks and other financial institutions. A chequing deposit is a loan by a depositor to a bank, the ownership being transferable from one person to another by writing an instruction to the bank -a chequeasking the bank to alter its records. Chequing deposits may then be called deposit money. Note that chequing deposits are money, but cheques are not. When you pay with a 6 cheque you don't increase the quantity of money in the economy. You just transfer the amount written on the cheque from your account to the account of the person who receives the cheque. Credit cards are not money either. A credit card is only an ID card, as your driver's licence, which allows you to purchase something with the promise of repaying later. When you make a purchase, you sign a credit-card sales slip that creates a debt in your name. 15.1.5 Money in Canada Today There are three main economic measures of money in current use: M1, M2, and M3. M1 = currency held outside banks + privately held demand deposits at chartered banks and all other financial institutions M2 = M1 + personal and non-personal notice deposits at chartered banks and all other financial institutions M3 = M2 + personal and non-personal fixed-term deposits at chartered banks and all other financial institutions In our analysis we are going to treat all forms of deposits as only one (D), and thus money (M) will be M = CUP + D, where CUP is currency in circulation outside the banking system. Note that the total currency in the economy (CU) is equal to the currency held by the public (CUP) plus the currency held by the banks in their vaults (CUB): CU = CUP + CUB. 7 15.2 THE BANKING SYSTEM 15.2.1 The Bank of Canada The Bank of Canada is Canada's central bank. A central bank is a public authority charged with regulating and controlling a country's monetary and financial institutions and markets. The Bank of Canada is also responsible for the nation's monetary policy. Monetary policy is the attempt to control inflation and the foreign exchange value of the Canadian currency, and to moderate the business cycle by changing the quantity of money in circulation and adjusting interest rates. The Bank of Canada is relatively independent from the central government. Only when there is a strong disagreement about monetary policy between the government and the Bank does the governor of the Bank resign. The main functions of the Bank of Canada are: 1) Banker to the Chartered Banks The Bank of Canada accepts deposits from the chartered banks and will, on order, transfer them to the account of another bank. The deposits of the chartered banks with the Bank of Canada are an asset from the point of view of the chartered banks, but a liability from the point of view of the Bank of Canada. 2) Lender of Last Resort to Chartered Banks The Bank of Canada finances settlement payments between banks when banks reserves (i.e., deposits of the chartered banks at the Bank of Canada) are not sufficient. 3) Banker to the Government 8 The government keeps its chequing deposits at the Bank of Canada. The government also borrows from the Bank of Canada by selling government securities (bonds) to the Bank. 4) Controller and Regulator of the Money Supply The Bank of Canada controls the money supply, mainly through the purchase and sale of government securities (bonds). The balance sheet of the Bank of Canada is a statement that lists the Bank’s assets and liabilities. Assets are things of value that the Bank owns. Liabilities are things that the Bank owes to other institutions. Bank of Canada’s assets are, for instance, the government securities (bonds) it owns, loans to chartered banks, and foreign-currency reserves. Bank of Canada’s liabilities are, for instance, the total currency in circulation outside and inside the banking system, the deposits of the chartered banks, and the deposits of the Government of Canada. Note that what is an asset for the Bank of Canada is at the same time a liability to someone else, and what is a liability to the Bank of Canada is at the same time an asset to someone else. 15.2.2 Financial Intermediaries A financial intermediary is a firm that takes deposits from households and firms and makes loans to other households and firms. There are three types of financial intermediaries whose deposits are components of the nation's money: 1) chartered banks 2) trust and mortgage loan companies 3) local credit unions and caisses populaires. 9 The differences between these three types of financial institutions have been reduced in recent times, and thus we are going to talk about chartered banks when referring to the banking system in general. The balance sheet of a chartered bank is a statement that lists the banks' assets and liabilities. Assets are things of value that the bank owns. Liabilities are things that the bank owes to households and firms. A chartered bank's assets are, for instance, its deposits with the Bank of Canada, the government securities (bonds) it owns, the currency in its vault, the loans made to its customers, etc. A chartered bank's liabilities are, for instance, the deposits of its customers, the deposits of the Government of Canada, etc. Note that what is an asset for the chartered bank is at the same time a liability to someone else, and what is a liability to the chartered bank is at the same time an asset to someone else. For instance, both the chartered bank's deposits with the Bank of Canada and the currency it holds represent liabilities to the Bank of Canada. Similarly, the public's deposits with the chartered bank represent an asset from the point of view of the public. 15.3 HOW BANKS CREATE MONEY 15.3.1 Reserves Banks need to keep some cash in their vaults in order to meet depositors' day-to-day requirements for cash. They also need to keep some deposits with the Bank of Canada to settle accounts with other banks (transfers of deposits to other banks). The sum of the cash held by the chartered banks in their vaults (CUB) and their deposits with the Bank of Canada (DBC) constitute the chartered banks' reserves (RE): RE = CUB + DBC. 10 However, Banks don't need to have $100 in cash or on deposit at the Bank of Canada for every $100 that people have deposited with them. As a matter of fact, banks today have about $1 in cash or on deposit at the Bank of Canada for every $100 deposited in it. Banks have learned from experience that these reserve levels are adequate for ordinary business needs. The fraction of a bank's total deposits that are held in reserves is called the reserve ratio (v): v = RE/D, where D represents customers' deposits with the chartered banks. All banks have a desired reserve ratio. The desired reserve ratio is the ratio of reserves to deposits that banks regard as necessary in order to be able to conduct their business. Before 1994, the desired reserve ratio was determined partly by regulation and partly by what the banks regarded as the minimum safety level for their reserve holdings. Government regulation used to set the minimum required reserve ratio. Banks, however, could choose to hold a reserve ratio above this minimum. This implied that the required reserves may differ from the desired reserves. At any point in time, banks may hold reserves at a level different from the desired level. The difference between actual reserves and desired reserves is excess reserves or insufficient reserves. 11 15.3.2 The Creation of Money Whenever banks have excess reserves, they are able to create money. Remember that money is equal to currency outside the banking system (CUP) plus deposits (D): M = CUP + D. Banks can't affect the component CUP of the money supply (it depends on the public's preference between cash and deposits), but they can affect the component D of the money supply. Banks can create deposits (D) by making loans to their customers. Let's have a look at an example. Suppose that there is only one chartered bank with a desired reserve ratio of 20 percent (v = 0.20). Suppose that a customer of this bank decides to reduce her holdings of currency and deposits $100 in her account. The changes in the balance sheets of the public and of the chartered bank are as follows: Public Assets CUP D Chartered Bank Liabilities –100 +100 Assets CUB +100 Liabilities D +100 After this first step, the money supply (M) has not changed yet. Any change in the money supply would be equal to: ∆M = ∆CUP + ∆D. And since ∆CUP = –100 and ∆D = +100, then ∆M = 0. Note that since deposits have increased by $100, the chartered bank should increase its reserves by $20 in order to keep the desired reserve ratio of 20%. However, the actual reserves of the chartered bank have increased by $100 since 12 reserves (RE) are equal to: RE = CUB + DBC. That is, actual RE have increased by the increase in CUB. Since the change in actual reserves ($100) is greater than the change in desired reserves ($20), the chartered bank is now holding excess reserves of $80. What the chartered bank will do now is to lend these excess reserves of $80 to some of its customers, thus increasing these customers' deposits at the bank by $80. The corresponding changes in the balance sheets are as follows: Public Assets CUP D D Chartered Bank Liabilities –100 +100 +80 L Assets +80 CUB D +100 +80 Liabilities D D +100 +80 After this second step, the money supply has increased: ∆M = ∆CUP + ∆D = –100 + (100 + 80) = 80. But this is not the end of the story. The chartered bank desired change in reserves is 20% of the change in deposits of $180, that is, $36. The actual change in reserves, however, is still $100. Therefore, after the second step, the chartered bank reduced its excess reserves but still holds $64 in excess reserves. Once again, the chartered bank will lend out this excess reserves to some of its customers, thus increasing D by $64. The accumulated changes in the balance sheets are as follows: 13 Public Assets CUP D D D –100 +100 +80 +64 Chartered Bank Liabilities L L Assets +80 CUB +64 L L +100 +80 +64 Liabilities D D D +100 +80 +64 After this third step, the money supply has increased by $144: ∆CUP = –100 and ∆D = +244. The chartered bank desired change in reserves is 20% of the change in deposits of $244, that is, $48.80. The actual change in reserves, however, is still $100. Therefore, after the third step, the chartered bank has reduced its excess reserves but still holds $51.20 in excess reserves. Once again, the chartered bank will lend out this excess reserves and the process will continue. The process will come to an end when all excess reserves have been eliminated. At this time, the banking system would have increased the money supply by the initial change in reserves times the money multiplier (mm): ∆M = mm ∆RE. 15.3.3 The Simple Money Multiplier The money multiplier (mm) is equal to the change in money supply divided by the change in reserves: ∆M mm = ∆RE And assuming no cash drain from the banking system, then ∆M = ∆D and mm = ∆D / ∆RE. Now, if the desired reserve ratio (v) is fixed and there is no cash drain from the banking 14 system, then v = ∆RE / ∆D, and mm = ∆D / ∆RE = 1 / v. In our example, v is 0.20 and thus the corresponding money multiplier is 5. Hence, at the end of the multiplying process the money supply will have increased by 5 times the initial change in reserves, that is, by $500. Therefore, the total change in the money supply will be equal to the summation of this increase in deposits ($500) minus the initial decrease in cash holdings ($100), or a total of $400. Indeed, since mm = ∆D / ∆RE = 1 / v, ∆D = mm ∆RE = 5 ($100) = $500. This analysis suggests that there must be an increase in reserves (RE) in order to have an increase in the money supply (M). 15.4 THE BANK OF CANADA'S CONTROL OVER THE MONEY SUPPLY We indicated that one of the main functions of the Bank of Canada was to control or regulate the supply of money. In order to achieve this goal, that is, in order to alter the supply of money, the Bank of Canada must affect the reserves of the chartered banks. The main instrument used by the Bank of Canada to affect the chartered banks' reserves and thus control the money supply is open market operations. An open market operation is a purchase or sale of Government of Canada securities (treasury bills and bonds) by the Bank of Canada. When the Bank of Canada buys Government Bonds from the public or the chartered banks, the supply of money increases. When the Bank of Canada sells Government Bonds to the public or the chartered banks, the supply of money decreases. 15 15.4.1 An Open Market Purchase Let’s assume that there is no cash drain in banking system (i.e., ∆CUP = 0) and that the desired reserve ratio is fixed at 0.20 (and thus mm = 5). Let’s further assume that there is only one chartered bank. Suppose that the Bank of Canada buys $100 worth of Government Bonds from the public. The changes in the balance sheets of the public, the chartered banks, and the Bank of Canada are as follows: Public Assets GB D –100 +100 Liabilities Chartered Bank Assets DBC +100 Bank of Canada Liabilities D +100 Assets GB Liabilities +100 DBC +100 The public sells an asset in the form of Government Bonds, and the Bank of Canada acquires an asset in the form of Government Bonds. Therefore, the item "Government Bonds" in the assets column decreases by $100 in the public's balance sheet and increases by the same amount in the Bank of Canada's balance sheet. The Bank of Canada buys these bonds by writing a cheque which the public deposits at the chartered bank. Therefore, the item "deposits" in the assets column of the public increases by $100. These deposits represent a liability from the point of view of the chartered bank, and thus the liabilities column of the bank increases by $100. Now the chartered bank has the cheques written by the Bank of Canada and thus holds a claim on the Bank. The chartered bank deposits these cheques at the Bank of Canada, and thus its deposit increases by $100. After the Bank of Canada's purchase of the bonds, the money supply increased by $100 (equal to the change in deposits). Also, since the chartered bank’s deposits with the Bank of Canada are part of the chartered bank’s reserves, the reserves increased by $100. 16 Now, through the multiplying mechanism, the money supply will increase by the money multiplier times the change in reserves: ∆M = mm ∆RE = 5 ($100) = $500. Therefore, the final changes in the balance sheets (i.e., after the chartered bank eliminates all excess reserves) would be as follows: Public Assets GB D D Chartered Bank Liabilities –100 L +100 +400 Assets +400 DBC L Liabilities +100 D +400 D +100 +400 Bank of Canada Assets GB Liabilities +100 DBC +100 We could have obtained the same result had the Bank of Canada bought the bonds from the chartered banks instead that from the public. In this case, the changes in the balance sheets would have been as follows: Public Assets D +500 Chartered Bank Liabilities L Assets +500 GB DBC L Liabilities –100 D +100 +500 +500 Bank of Canada Assets GB Liabilities +100 DBC +100 17 15.4.2 An Open Market Sale Suppose that the Bank of Canada sells $100 worth of Government Bonds to the public. The changes in the balance sheets of the public, the chartered banks, and the Bank of Canada are as follows: Public Assets GB D Liabilities +100 –100 Chartered Bank Assets DBC –100 Bank of Canada Liabilities D –100 Assets GB Liabilities –100 DBC –100 The public buys an asset in the form of Government Bonds, and the Bank of Canada sells an asset in the form of Government Bonds. Therefore, the item "Bonds" in the assets column increases by $100 in the public's balance sheet and decrease by this amount in the Bank of Canada's balance sheet. The public buys these bonds by writing cheques. Therefore, the item "deposits" in the assets column of the public decreases by $100. These deposits represent a liability from the point of view of the chartered bank, and thus the liabilities column of the bank decreases by $100. Now the Bank of Canada has the cheques written by the public and thus holds a claim on the chartered bank. The chartered bank’s deposits with the Bank of Canada thus decrease by $100. After the Bank of Canada's sale of bonds, the money supply has decreased by $100 (equal to the change in deposits). Also, since the chartered bank’s deposits with the Bank of Canada are part of the chartered bank’s reserves, the reserves decreased by $100. 18 Now, through the multiplying mechanism, the money supply will decrease by the money multiplier times the change in reserves: ∆M = mm ∆RE = 5 (–$100) = –$500. In order to decrease the public's deposits by $500 (i.e., by an additional $400), the chartered bank will have to recall $400 in loans. Therefore, the final changes in the balance sheets would be as follows: Public Assets GB D D Chartered Bank Liabilities +100 L –100 –400 –400 Assets DBC L –100 –400 Liabilities D D –100 –400 Bank of Canada Assets GB Liabilities –100 DBC –100 We could have obtained the same result had the Bank of Canada sold the bonds to the chartered banks instead of to the public. The changes in the balance sheets would have been as follows: Public Assets D –500 Chartered Bank Liabilities L –500 Assets GB DBC L Liabilities +100 D –100 –500 –500 Bank of Canada Assets GB Liabilities –100 DBC –100