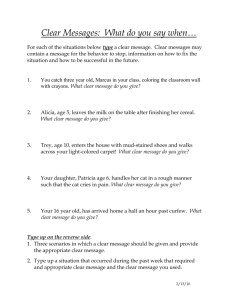

guide!to!teaching! &!faculty!life! - John Jay College of Criminal Justice

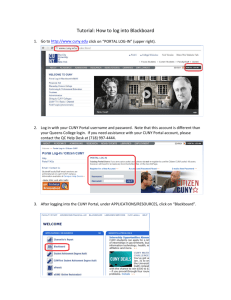

advertisement