Institutional strength, social control and neighborhood crime rates

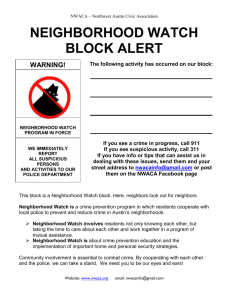

advertisement